Beer Brand Battle at the 100th Meridian

By Richard Stobbe

A Canadian band, The Tragically Hip, has sued a brewer for the use of a beer name that mimics the title of one of the band’s popular songs.

Mill Street Brewery, a brand owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev (the world’s largest brewer), has a beer branded as “100th Meridian Organic Amber Lager” .

This sounds familiar to fans of the The Hip, who will recall rockin’ out to the opening power chords of the 1992 hit entitled “At The Hundredth Meridian” from the Fully Completely album.

Does the name of a song from the 1990s take on the attributes of a trademark? Does the use of song title create a false association with the band, such that the band’s trademark rights are infringed? What if the name of the song ( “At The Hundredth Meridian” ) is not identical to the beer name (“100th Meridian”)? Does it make a difference if other brewers have given a nod to The Hip (Fully Completely IPA from Phillips Brewing, Ahead by a Century IPA, Tragically Hopped Double IPA, what’s with all the IPAs? heck there’s even a 50 Mission Cap Brewing Co.!).

This week, The Hip sued Trillium Beverage the brewer of the Mill Street product (Trillium is owned by Labatt Brewing Company, which in turn is owned by the conglomerate AB InBev), claiming trademark infringement. This is a tricky one for a couple of reasons, particularly since the brewer owns a registered trademark for “100th MERIDIAN” for beer. The Hip will face an uphill battle there. However, Mill Street didn’t do itself any favours by posting pictures on social media of the beer next to Tragically Hip albums, clearly suggesting some kind of association.

Related Reading: The Tragically Hip sue Mill Street Brewery over 100th Meridian beer

The lawsuit will likely settle, but if it does go through to a judgement on its merits, it will be an interesting one to watch.

Calgary – February 10, 2021

No commentsInfringing Trademarks Cannot Remain on the Register

By Richard Stobbe

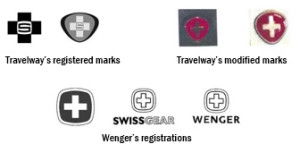

In a battle between the suitcase makers, the Federal Court of Appeal found that Travelway Group International Ltd. (Travelway), had infringed the trademarks owned by Wenger, and had passed off its own goods as Wenger’s. The Court granted Wenger a declaration of trademark infringement, ordered a permanent injunction prohibiting Travelway from using its infringing marks, and ordered Travelway to destroy or deliver up all wares, packages, labels and advertising material.

Basically, this was a complete victory for the well-known Swiss-cross style Wenger brand, depicted below.

However, the Federal Court of Appeal decision resulted in an anomaly: at the time of the trademark infringement lawsuit in 2013, the trademarks of both Wenger and Travelway were registered in Canada. In the appeal decision, the Court concluded, ultimately, that “each of the Travelway marks is confusing with each of the Wenger marks”, but the Court left the registrations in place, with the result that infringing, invalid trademarks were nevertheless maintained on the register in Canada.

The court in Wenger SA v. Travelway Group International Inc., 2019 FC 1104 (CanLII), corrected this, expunging the Travelway marks.

It’s also worth noting that the Travelway registrations were not found to be void ab initio, and thus benefited from the protection granted by section 19 of the Trademarks Act, which indicates that a registration is a defence to infringement. The court appears to have accepted Travelway’s argument that the protection of section 19 should extend to the variants of the Travelway marks, given that the Federal Court of Appeal found them to be permissible variants.

Related Reading: CANADA: Infringing Trademark Registrations Must Be Expunged, Court Finds

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCraft Beer Trademarks: The Ol’ Cease & Desist

By Richard Stobbe

Local Alberta breweries Elite Brewing (visited, love the carbon fibre bar) and Bow River Brewing have been on the receiving end of a cease and desist letter from the City of Calgary over a beer label for Fort Calgary ISA (a “richly hopped lighter bodied India session ale”).

The complaint by the City related to the unauthorized use of “FORT CALGARY”, which is an official mark owned by the City.

But wait, isn’t “FORT CALGARY” also an historical landmark and a place name?

From reading our other articles on geographical locations as trademarks, you might wonder how this works. You might say “Hang on… if a trademark is based on a geographic name, and a trademarks examiner decides that the geographic name is the same as the actual place of origin of the products, won’t the trademark be considered ‘clearly descriptive’ and thus unregistrable as a trademark? Furthermore, if the geographic name is NOT the same as the actual place of origin of the goods and services, the trademark will be considered ‘deceptively misdescriptive’ since the ordinary consumer would be misled into the belief that the products originated from the location of that geographic name. If that’s true, then how can a trademark owner assert rights over a geographic location?”

Yes, yes, that’s all true, with some exceptions, but according to Canadian trademark law there is also something called an official mark, which is what the City of Calgary owns. This is a rare species of super-mark that effectively sidesteps all of those petty concerns regarding geographical locations, ‘clearly descriptive’ and ‘deceptively misdescriptive’.

By virtue of its status as a government entity, the City can assert rights in certain marks that it adopts under Section 9 of the Trademarks Act.  These rights form the legal basis for the City’s recent cease and desist letter regarding the FORT CALGARY beer label.

This case has some unique elements due to the special rights that the City claims under the Trademarks Act, but the general message is the same: craft brewers can benefit from some preliminary trademark clearance searching when they launch a brand or a new beer name. And they should seek advice if they’re on the receiving end of this kind of letter.

In the end, the brewers reportedly agreed to sell out their remaining stock and refrain from further use of the Fort Calgary label, and the City agreed not to commence a lawsuit.

Need advice on beer trademarks and clearance searching? Contact craftlawyers.ca.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

No commentsAttacking Bad Faith Trademark Registrations in Canada

By Richard Stobbe

There are a number of monumental changes coming soon (June, 2019) to the trademark regime in Canada. One small change was actually first introduced in 2018, a change that may come in handy in some trademark disputes once the rest of the new provisions are in force.Â

The concept of “bad faith†became a formal part of the Trademarks Act in Canada in late 2018, and it remains to be seen how it might be developed as a tool to prevent unmeritorious applications or registrations.Â

One of the fears among some trademark owners is the perception that “use†has been dropped as a requirement for registration, clearing a pathway for trademark squatters who file extortionist or opportunistic applications where legitimate use was never intended. In fact, “use†remains a fundamental requirement under Canadian trademark law, but it is true that under the revised Act, a “Declaration of Use†will be dropped as a necessary step before registration; it is currently required for applications filed on the basis of proposed use, and that requirement falls away under the revised  Act.

The ability to attack a trademark on the basis of “bad faith†is supposed to provide an easier way to challenge opportunistic applications which might be filed without any intention of actual commercial use. This is a new ground for invalidating a trademark registration or opposing an application, which is embedded in Section 18 of the Act (“The registration of a trade-mark is invalid …. if the application for registration was filed in bad faithâ€). There is no definition of “bad faith†in the Act but at least one Canadian case considered the issue several years ago:  HomeAway.com, Inc. v. Hrdlicka, 2012 FC 1467 (CanLII) Â

In HomeAway, the Federal Court considered a case where an individual, Mr. Hrdlicka, filed an application for the mark VRBO, and obtained a registration for that mark in association with “Vacation real estate listing servicesâ€.Â

The VRBO mark is, of course, an acronym for “vacation rental by ownerâ€, and a well-known brand owned by HomeAway.com Inc. Mr. Hrdlicka obtained registration of the mark in Canada because he apparently filed a blank “Declaration of Useâ€, thus somehow securing the registration despite the lack of any declaration of use, or any actual evidence of use in Canada. The Federal Court found that the applicant never used VRBO as a trade-mark in Canada (until dubious evidence emerged after the dispute arose), and that, at the time he applied to register that trade-mark in Canada, Mr. Hrdlicka was aware of HomeAway’s business. The evidence showed that he registered the mark for the purpose of selling it back to HomeAway “for a large sum of money and/or for employment or royalties.† This is reminiscent of many dot-ca domain name disputes.Â

As a result, the Federal Court concluded that Mr. Hrdlicka, in filing the application for registration, “had no bona fide intent of using it in a legitimate commercial way in Canada. His intent was to extort money or other consideration from HomeAway. Such activity should not be condoned or encouraged.†The court decided to expunge the registration, relying on its general powers under Section 57 of the Act.Â

This is precisely the circumstance that concerns current brand owners in light of the pending changes to the Trademarks Act: opportunistic registration, no bona fide purpose, and no evidence of actual use.

While the term “bad faith†does not actually appear in the HomeAway judgement, the result is clear: the application or registration of a mark without any bona fide intent or legitimate commercial use, will be considered to be filed for an improper purpose, and such conduct lacking good faith intent should be considered “bad faith†within the scope of Section 18(e). Â

It remains to be seen whether courts apply this decision to future Section 18(e) challenges.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsPour a Glass of Trademarks

By Richard Stobbe

In time for the holidays, this is tale of competing brands sloshing around the marketplace. Please enjoy responsibly.

Diageo North America, Inc. is purveyor of some of the world’s best-known brands of spirits and beer, some of which are probably in your cupboard somewhere: Crown Royal, Baileys, Smirnoff, Johnny Walker, Captain Morgan, Tanquery and Gordon’s Gin, Guinness and Kilkenny, among many others. In two parallel trademark disputes, Diageo recently faced off with Constellation Brands, one of Canada’s largest producers and distributors of wines.

In Constellation Brands Canada, Inc. v Diageo North America, Inc., 2018 TMOB 133 (CanLII), Diageo applied for the trademarks:

- MAKE IT NAKED for use in association with distilled spirits, namely rum and rum-flavoured beverages.

- DON’T WORRY DRINK NAKED & Design also for use in association with distilled spirits, namely rum and rum-flavoured beverages.

In Arterra Wines Canada, Inc. v Diageo North America, Inc., 2018 TMOB 134 (CanLII), Diageo applied to register three variations of the trademark:

- THE NAKED TURTLE for use in association with distilled spirits, namely rum and rum-flavoured beverages (vodka and beer excluded).

Constellation Brands/Arterra Wines owns the popular NAKED GRAPE family of trademarks, for use in association with wine, wine spritzers, and icewine.  These guys sell a lot of wine: between 2008-2015 yearly sales of NAKED GRAPE branded wines ranged between $16-26 million across Canada.

Are the Diageo marks confusing with the NAKED GRAPE marks?

Interestingly, the legal test for confusion reflects the modern consumer: The test to be applied is a matter of first impression in the mind of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry who sees the mark at a time when he or she has no more than an imperfect recollection of the prior brand, and does not pause to give the matter any detailed consideration or scrutiny. Hmmm.. apparently we’re a nation of consumers in a hurry and we don’t pause to give things any detailed scrutiny. Let’s leave the philosophical implications for a future discussion.

Test to Determine Confusion

The test to determine the issue of confusion is found in the Trademarks Act: the use of one trademark causes confusion with another trademark if the use of both marks in the same area would likely lead a consumer to infer that the associated goods are both manufactured and sold by the same person. Courts look at:

- the inherent distinctiveness of the trade-marks and the extent to which they have become known;

- the length of time the trade-marks have been in use;

- the nature of the goods and services or business;

- the nature of the trade; and

- the degree of resemblance between the trade-marks in appearance, or sound or in the ideas suggested by them; oh, and don’t forget

- “all the relevant surrounding circumstances.”

In the end, three of the five Diageo marks were refused. For the marks MAKE IT NAKED, DON’T WORRY DRINK NAKED & Design and THE NAKED TURTLE Design, the final decision was that a casual consumer with an imperfect recollection of the NAKED GRAPE trademark who encounters rum or rum flavoured beverages sold under any of these brands may think that these goods are sold by the owner of the NAKED GRAPE mark, due to resemblance between the marks.

One Design Survives

However, one of the design marks was permitted to go ahead: The Naked Turtle Design – front label (Application No. 1592265) was one of the variations among Diageo’s applications. Here, the decision was different since the most striking aspect of this mark was the phrase THE NAKED TURTLE and the depiction of the turtle lounging in a hammock between two palm trees. As turtles do. For this mark, it was considered to be more different than alike as a matter of first impression.

One Word Mark Survives

The opposition was also refused for one of the word marks ( THE NAKED TURTLE) (Application No. 1561944). For this application, there was no reasonable likelihood of confusion between the trade-marks even though the nature of the goods and channels of the trade overlaps.

What are the lessons in this case?

- Sub-brands are becoming more and more important within a competitive marketplace such as sales of alcoholic beverages.

- This illustrates the extent to which highly competitive industry subsectors will clash even where the products are different within the sector – distilled spirits, such as rum, are very different from wines, wine spritzers, and icewine. One is an alcoholic beverage made from the fermentation of grapes and one is a spirit produced through distillation. However, the goods and channel of trade are considered to overlap, even though the products are sold in different areas of the store.

- In its defence, Diageo tried to cite other alcoholic beverages where the word “naked” appears in the label: Back Forty Naked Pig Pale Ale, Four Vines Naked Chardonnay, Naked on Roller Skates, Naked Winery wines, Nøgne Ø Naked Kiss Imperial Porter, Barenaked Vodka, and Snoqualmie Naked Riesling. This is considered “cheeky advertising” according to the decision. Diageo argued that because there are other such brands available, consumers are accustomed to seeing this term with alcoholic beverages and thus can distinguish between marks that include this element. The decision-maker was not convinced, and dismissed this as “limited evidence” of the use of this term by other parties in Canada.

- Diageo pursued a strategy of filing a range of applications, both word marks and design marks, including both the front and back labels of the bottle. This strategy proved to be successful – or, at least it help avert complete disaster. Unless it’s challenged on appeal, two of Diageo’s marks will proceed to registration, permitting Diageo to carve out registered trademark protection for its NAKED TURTLE brand.

To review trademark strategies for distilled, brewed or fermented products, contact us at craftlawyers.ca or visit us on the Instagram.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

LEGO vs. LEPIN: Battle of the Brick Makers!

By Richard Stobbe

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

The LEGO Group recently announced a win in Guangzhou Yuexiu District Court in China, based on unfair competition and infringement of its intellectual property rights in 3-dimensional artworks of 18 LEGO sets, and a number of LEGO Minifigures. This resulted in an injunction prohibiting the production, sale or promotion of the infringing sets, and a damage award of RMB 4.5 million.

While this decision is hailed as a win for LEGO, and a blow in favour of IP rights enforcement in China, the commercial reality is that 18 sets is a drop in the proverbial ocean of counterfeits for LEGO. A quick spin around the Lepin website shows that there is a sprawling product line available to the marketplace, most of which are direct copies of the corresponding LEGO sets. These are copies in appearance at least, since the quality of the Lepin product is … different, when compared to the quality of LEGO branded merchandise, according to some online reviews.

The connectable plastic brick which was popularized by LEGO is not, in itself, protectable from the IP perspective (patents expired long ago, and the trademarks in the brick shape were struck down in Canada). This permits entry by competitors such as MEGA-BLOKS, a company that sells a virtually identical interlocking brick, but under a distinctive brand, with original set designs, and rival licensing deals of its own Рfeaturing the likes of Pok̩mon, Sesame Street, John Deere and Star Trek.

While the bricks are just bricks, the LEGO trademarks are protectable, and as LEGO established, so are the rights in three-dimensional set designs, packaging art and other elements that were shamelessly copied by the busy folks at Lepin.

Protection of market share is a complex undertaking, where an intellectual property strategy is one element.  Looking for advice on how to protect your business using IP as a tool? Contact our IP advisors to start the conversation.

Related Reading: Battle of the Blocks (looking at the battle between Lego and Mega Blocks in Canada).

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Can an old trademark be reborn… with a new owner?

By Richard Stobbe

When a Canadian woman looked to buy CUBAN LUNCH brand chocolate bars for her mother, she found the product was discontinued.

It appears that an Albertan, Crystal Regehr Westergard, saw an entrepreneurial opportunity.  After realizing the product had been abandoned by the original manufacturer, and the Winnipeg factory that made Cuban Lunch closed down nearly three decades ago, she decided to remake the product herself, and revive the trademark. The original trademark CUBAN LUNCH was registered in Canada in 1983 for “Confectionery namely chocolate bars”, claiming use in Canada since December 1948. After being passed through a number of different owners throughout the late 1990s up until 2013, the original trademark was finally expunged from the register at the Canadian Intellectual Property Office in 2015 for failure to renew. 1948-2015. Not a bad run for a candy bar brand.  This is usually the end of the line for an aging trademark, where the product has been discontinued.

The Westergards submitted a new trademark application to the Canadian Intellectual Property Office for the CUBAN LUNCH trademark, listing the same goods, and claiming use since May 2017.

This raises an interesting trademark question: Can an old, retired trademark be reborn with a new owner?

In Canada, trademark rights are based on use. Once use begins, trademark rights come alive. When use ceases, trademark rights die out. It’s important to remember that the registered rights recorded in the trademarks office are merely reflective of the actual use of that mark in the marketplace.  To use the more eloquent phrasing of the Supreme Court of Canada: “Registration itself does not confer priority of title to a trade-mark. At common law, it was use of a trade-mark that conferred the exclusive right to the trade-mark. While the Trade-marks Act provides additional rights to a registered trade-mark holder than were available at common law, registration is only available once the right to the trade-mark has been established by use.” (Emphasis added) (Masterpiece Inc. v. Alavida Lifestyles Inc., [2011] 2 SCR 387, 2011 SCC 27 (CanLII))

Trademark rights lapse and die all the time, where the rights are no longer used, and are therefore legally extinguished. In theory, there is no reason why a new business owner cannot commence use of a “dead” mark and notionally adopt that mark as their own, breathing new life into the trademark rights through their own use of the mark with their own product. Of course, it’s important to note that even if registered rights lapse (for example, for failure to pay renewal fees), the underlying common law rights might continue. Let’s say a registration lapsed because of a clerical oversight; this oversight alone would not impact the underlying commercial use of the mark which might be alive and well. As noted above, registration is merely an official recordal of the rights endowed by actual use.

In the case of the CUBAN LUNCH mark, the reports appear to indicate that the original mark suffered a death both in actual commercial use and in registration. If that’s the case, then the original trademark is no longer a trademark, and those words are free to be adopted by a new owner.

Now… it’s high noon. Where do we buy a CUBAN LUNCH ?

Calgary – 07:00

No comments

BEER BEER as a trademark… for “beerâ€?

By Richard Stobbe

There is a rule in Canadian trademarks law that you can’t get a trademark for a word that describes the product you’re selling. Makes sense, right? No-one should have a monopoly over a word that is descriptive of the thing they’re selling. Such a term should be open to everyone to use.

Drummond Brewing applied to register BEER BEER as a trademark for “beerâ€.  Wait, let’s re-read the paragraph above. Isn’t BEER BEER clearly descriptive when used in association with the sale of beer?  Drummond, apparently, did not think so when it filed its application claiming use since 2009. They held this opinion despite an earlier decision (Coors Global Properties, Inc. v. Drummond Brewing Company, 2011 TMOB 44 (March 11, 2011)) which found BEER BEER to be clearly descriptive.

There is well-known decision from the early 1980s (Pizza Pizza Ltd. v. Registrar of Trade Marks (1982), 67 C.P.R. (2d) 202), where the court decided that the mark PIZZA PIZZA was found not to be clearly descriptive of “pizza†since the expression PIZZA PIZZA was not a linguistic construction that is a part of normally acceptable spoken or written English. If it works for pizza, why not beer?

In the decision Molson Canada 2005 v Drummond Brewing Company Ltd., 2017 TMOB 78 (CanLII),  Molson opposed this trademark, and Drummond fought back, insisting that the mark was not descriptive. Numerous experts from both sides weighed in on the meaning of the term BEER BEER as a linguistic construction. One expert provided an opinion as a sociolinguist after  consulting scholarly literature, fellow linguists, and the Corpus of English Contrastive Focus Reduplications, a collection of 203 examples of naturally occurring utterances featuring contrastive reduplicative constructions, as published in the scholarly journal Natural language and Linguistic Theory (NLLT), 2004.

I’m not making this stuff up.

In the end, common-sense prevailed and the decision-maker found that the mark BEER BEER was clearly descriptive of the product. The mark was found to be unregistrable as a trademark.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Canadian Beer Trademarks: When is a moose just a moose?

HEAD OF MOOSE DESIGN

By Richard Stobbe

When is a moose just a moose?

Apparently when it is reclined in a parlour sipping gin.

In Moosehead Breweries Limited v Eau Claire Distillery Ltd., 2018 TMOB 24 (CanLII), Canadian brewer Moosehead Breweries, the oldest, privately owned, independent brewery in Canada complained about confusion based on its well-known moose marks for beer (including Registration number TMA667312, as shown above).

Moosehead alleged that the PARLOUR GIN DESIGN for gin (Application No. 1,667,113) owned by Alberta’s own Eau Claire Distillery Ltd., was confusing with Moosehead’s own moose marks for beer.  In Eau Claire’s mark, an anthropomorphic moose character and anthropomorphic bear character are seated in formal clothing amidst Victorian parlour furnishings, sipping gin and engaging in polite conversation. Does the use of the moose for gin make this mark confusing with Moosehead’s brand for beer?

Canadian courts tell us that the test for confusion is “a matter of first impression in the mind of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry who sees the [mark], at a time when he or she has no more than an imperfect recollection of the [prior] trade-marks, and does not give pause to give the matter any detailed consideration or scrutiny, nor to examine closely the similarities and differences between the marks.”

In this case, the decision-maker dismissed Moosehead’s opposition, after going through the factors, namely: (a) the inherent distinctiveness of the trade-marks and the extent to which they have become known; (b) the length of time each has been in use; (c) the nature of the goods, services or business; (d) the nature of the trade; and (e) the degree of resemblance between the trade-marks in appearance or sound or in the ideas suggested by them. There is no reasonable likelihood of confusion since the marks bear little resemblance in appearance, sound, and in the ideas suggested by them.

Moosehead’s challenge was rejected, and the Eau Claire mark will proceed.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 2, let’s review the next couple of areas:

- Industrial Design or “Design Patentâ€:

I always tell my clients not to underestimate this lesser-known area of IP protection. It can be a very powerful tool in the IP toolbox. In both Canada (which uses the term industrial design) and the US (which refers to a design patent), this category of intellectual property only provides protection for ornamental aspects of the design of a product as long as they are not purely functional . To put this another way, features that are dictated solely by a utilitarian function of the article are ineligible for protection.

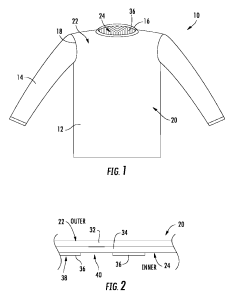

Registration is required and protection expires after 10 years. A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration. Some examples:  This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

The solid lines on the image above represents a protected design registration filed by Nike.

TIP: Placement of a pocket on a t-shirt may not be considered innovative, but even minor differentiators can help distinguish a product in a crowded field. A design registration can support a blended strategy which also deploys other IP protection, such as trademark rights.

- Trademarks:

Every consumer will be intuitively familiar with the power of a brand name such as LULULEMON or NIKE, or the well-known Nike Swoosh Design. That topic is well-covered elsewhere. However, some brands take advantage of a lesser-known area of trademark rights: distinguishing guise protects the shape of the product or its packaging. It differs from industrial design, and one way to consider the distinction is that an industrial design protects new ornamental features of a product from when it is first used, whereas a distinguishing guise can be registered once it has been used in Canada so long that becomes a brand, distinctive of a manufacturer due to extensive use of the mark in the marketplace. It’s worth noting that the in-coming amendments to the Trademarks Act will do away with distinguishing guises.

One good example is the well-known shape of CROCS-brand sandals. The shape and appearance of the footwear itself has been used so long that it now functions as a brand to distinguish CROCS from other sandals. Just as with industrial design, the protected features cannot be dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.

Others have filed distinguishing guise registrations in Canada, including Canada Goose Inc. for coats and Hermès International for handbags.

TIP: For a distinguishing guise application, each applicant will have to file evidence to show that the mark is distinctive in the marketplace in Canada. That is not the case with a regular trademark, such a word mark or regular logo design.

We review the final areas of IP protection in Part 3.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Evolution: Part 2 (When Technology Changes)

By Richard Stobbe

Technology certainly evolves. Can a trademark evolve? In the world of intellectual property rights, a registered trademark can live on for a hundred years or more. If you registered a trademark in the 1800s, it could still be valid today. But will the underlying product be delivered to customers the same way? (See: Goodbye Floppy Disk, Hello Streaming Video: Trademark Evolution, Part 2).

- In the 1980s Canadian courts recognized that service delivery can evolve in the decision in BMB Compuscience Canada Ltd v Bramalea Ltd. (1988), 22 CPR (3d) 561 (FCTD). In that case, BMB applied to register the mark NETMAIL in association with a computer program. But the NETMAIL product was not sold as a physical object, and courts have recognized that software vendors can experience “unique difficulties†when attempting to associate a trade-mark with its software, since there is no label, packaging or hang-tag, as with other types of goods. The court in BMB Compuscience was prepared to take a flexible approach and permit a software vendor like BMB to demonstrate “use†of its mark for the purposes of the Trade-marks Act where the brand was shown on a computer screen during product demonstrations.

- This concept was more recently applied in Davis LLP vs. 819805 Alberta Ltd., 2016 TMOB 64, a Section 45 challenge to the registered trademark BIBLIOTECA. The mark BIBLIOTECA was registered in association with certain software “goodsâ€. The goods were described as “Computer software, namely a computer database containing information for use in the field of building design and construction.â€Â During the relevant period, the database was accessed by customers as part of an online service, without the sale of any tangible or physical product. The BIBLIOTECA decision adopted the reasoning in BMB Compuscience to allow the trademark owner to demonstrate “use†of the mark in ways that reflected technological changes in the way this product was delivered to customers.

- In the United States, the USPTO is running a pilot program to allow amendments to identifications of goods and services in trademark registrations due to changes in technology, including many cases where floppy disks and cartridges are being updated to reflect online streaming. For example, the mark PHOTODISC, owned by Getty Images, was originally registered in association with stock photography “contained in digital format on CD-ROMs.â€Â Through the amendment process, Getty Images is proposing an amendment to reflect the changes in how its stock photo products are delivered: “in digital format on electronic or computer media or downloadable from databases or other facilities provided over global computer networks, wide area networks, local area networks, or wireless networks…â€

- Perhaps the best reflection of this is the US registered mark for THE MARCH OF TIME, used in association with newsreels and originally registered in 1935. Embedded in the original trademark application is a description of the technological breakthrough of allowing motion pictures to be broadcast with sound: “motion picture films for use in connection with synchronized apparatus for simultaneously reproducing coordinated light and sound effect.â€Sadly, this piece of history is now being replaced with the bland description “Providing non-downloadable online videos featuring historical newsreel.†I guess that evokes the march of time !

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 1)

.

By Richard Stobbe

Complex technology like blockchain is in fashion. What about IP protection for seemingly simple items like shirts, shoes and undergarments? As competitors jostle for position in the fashion and apparel marketplace, how do intellectual property rights apply? Make no mistake, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patent”

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 1, let’s review the first two areas:

- Confidential Information

Confidential information or ‘trade secrets’ refers simply to information that has value to a designer or manufacturer because competitors don’t have access to the information. As long as the information is kept secret, and is only disclosed to others in confidence, then the secrets may remain protected as ‘trade secrets’ for many years. The confidential information may be made up of related business information, such as contacts of suppliers, pricing margins, new product ideas or prototype designs. The period of confidentiality may be short-lived in the case of a new product design: once the product is released to customers, it’s no longer confidential.

An owner of confidential information must take steps to maintain confidentiality, and the information should only be disclosed under strict terms of confidentiality (as part of a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), or confidentiality agreement).

If the confidential information is misappropriated, the owner can seek to enforce its rights by proving that the information has the required quality of confidentiality, the information was disclosed in confidence, and there was an unauthorized use or disclosure in a way that caused harm to the owner.

TIP: Ensure that you take practical steps to limit access to the confidential info. And when signing an NDA, make sure it doesn’t contain any terms that might inadvertently compromise confidentiality or give away IP rights.

- Patents

Many apparel and footwear companies rely heavily on patent protection to block competitors and gain an advantage in the marketplace.

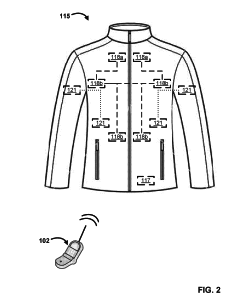

Let’s take a few examples. In pursuing the ‘holy grail’ of outdoor activewear, many manufacturers are seeking a comfortable, breathable jacket that can keep a wearer warm without overheating. The North Face System recently filed an application for a smart-sensing jacket using sensors to determine a “comfort signature” based on differences in environmental conditions between the sensors and making adjustments for the wearer.

A competitor – Under Armour Inc. – is seeking patent protection for garments incorporating printed ceramic materials to retain heat, without sacrificing other performance qualities such as  water and dirt repellency, durability, breathability and moisture-wicking qualities. In this patent application, Under Armour is seeking protection not only for the fabric but also the innovative method of manufacturing the fabric.

From high-tech jackets to innovative shoe designs, to more specific components, such as garment linings, or improved fasteners, patents can provide a valuable tool to ensure that a company’s research-and-development initiatives can bear fruit in the marketplace. By providing a period of exclusivity for the patent holder, this category of IP protection keeps the field clear of infringing replicas while the company recoups its investments and turns a profit on a successful product technology.

In the case of many fashion or apparel products, the time and cost of patent protection – it may take several years before a valid patent is issued – may not be justified in light of the high turn-over in seasonal product lines, and the ever-shifting tastes of consumers.

TIP: Make sure you consider both sides of the patent issue: as an inventor, an investment in patent protection may be worth considering, particularly in a product area where the underlying ‘technology’ or innovation may be commercialized over a number of years, such as the famous Gore-Tex fabric, even though superficial fashions may change during that time. On the flip side, manufacturers should take care to ensure that their own designs are not infringing the patent rights of some other patent holder.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 commentsCraft Beer Branding

By Richard Stobbe

In one of the more absurd episodes of bureaucratic overreach, craft brewer Stalwart Brewing Company ran into a regulatory headache when the LCBO raised concerns about the regulatory prohibition on health claims related to Stalwart’s label for ” Dr. Feelgood India Pale Ale”.

The regulator’s complaint was that the label – featuring a tongue-in-cheek portrayal of a snake wrapped around a mash-paddle-medieval-sword, mimicking a Rod of Asclepius – was somehow crossing the line by making unsubstantiated medical claims…Because apparently Canadian beer consumers wouldn’t be able to decipher that “Dr. Feelgood” is not a real physician, and might think that the IPA contained in the can was real medicine.

Leaving aside the thorny question of whether IPA qualifies as medicine, the branding and trademark issues arises in a number of ways:

- Trademark  searches can clear a proposed brand as against other similar marks which may be registered or pending for similar products;

- Trademark searches can be done in conjunction with the process of meeting federal and provincial labelling requirements;

- This case is a reminder that trademark preclearance must also take into account other rules, such as:

- alcohol by volume declarations;

- the correct naming for “low alcohol beer” vs. “light beer” vs. “extra strong beer”;

- “Lager” on its own is not an acceptable common name for beer. The common name “beer” must be listed in addition to the description “lager”;

- naming conventions related to gluten-free beer.

On a positive note, the original Dr. Feelgood cans should now be a collector’s item.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTrademark Evolution: Part 1 (When Trademarks Change)

By Richard Stobbe

The famous Toblerone bar is so distinctive in shape and design that it serves as a great example of a “distinguishing guise†trademark. It has been used as a  trademark since 1910 in Canada, and during that time has maintained the same “tread design†of chocolate peaks, which has been a registered trademark in Canada since 1969.

It’s the actual shape of the bar that functions as a trademark. The bar is really a whole trademark treasure-trove since the unique shape of the triangular box, the colour scheme of the lettering, and the word TOBLERONE, are all separate trademarks, registered in a number of countries around the world.

The Swiss chocolatier redesigned the famous bar for the UK marketplace (reportedly in response to price adjustments required in the wake of Brexit). The newly redesigned bar expanded the valleys, resulting in fewer peaks, all to shave costs.  This of course resulted in a minor scandal in the UK, as well as some heartburn for the company’s trademark counsel.

If the mark-as-used departs from the mark-as-registered, there is a risk that the original registered mark has been abandoned, putting the strength of the registered rights at risk. This is a basic tenet of trademark law. While minor changes are permitted as a brand evolves, there is a point at which the changes go too far, essentially resulting in the adoption of a new mark.

Seeing this vulnerability, a competitor entered the marketplace with a bar “inspired by†the original Toblerone bar. Poundland, a UK discount retailer, introduced a double-peaked chocolate bar complete with knock-off packaging that mimics the distinctive gold background and red lettering of the original Toberlone package.

After a legal wrangle that reportedly kept the Poundland product off store shelves for several months, the dispute was settled and Poundland introduced modified packaging, featuring gold lettering against a blue background.

The lessons for business?

- In the field of consumer products, this is a good reminder that the shape of the product or its packaging can serve as a trademark, and can be registered as a means of  protecting brand rights.

- When a product or trademark evolves over time – whether in response to cost pressures, as in the Toblerone case, or in response to changes in the marketplace, or consumer demands – it’s important to measure the modified mark against the original mark, as it was registered. If the departure is too great, the rights to the original mark may be placed at risk.

Calgary – 09:00 MST

No commentsWait… “GOOGLE” is not a generic word?

By Richard Stobbe

Is Google a brand or just a word meaning “conduct an online search”?

A trademark can suffer “genericide” when it becomes so commonly used that it transforms from a unique brand name into a generic word which is synonymous with a product or service. In a very interesting decision from the US Ninth Circuit Court Court of Appeals in Elliott and Gillespie v. Google Inc. , the trademark GOOGLE was challenged on this basis: that it had become a word describing “searching on the internet” in a general sense, rather than a being distinctive of search services provided through the GOOGLE-brand search engine.

The court had a good description of “genericide”: “Genericide occurs when the public appropriates a trademark and uses it as a generic name for particular types of goods or services irrespective of its source. For example, ASPIRIN, CELLOPHANE, and THERMOS were once protectable as arbitrary or fanciful marks because they were primarily understood as identifying the source of certain goods. But the public appropriated those marks and now primarily understands aspirin, cellophane, and thermos as generic names for those same goods.”

This case arose due to an underlying domain name complaint. Google asserted its trademark rights against Elliott and Gillespie based on their registration of hundreds of domain names that included the word “googleâ€; for example, “googledisney.com,†“googlebarackobama. net,†and “googlenewtvs.com.† Elliott and Gillespie fought back because hey, if you’re going to fight back, why not take on Google? They petitioned to cancel the trademark registrations for GOOGLE, which would in turn eliminate the basis for Google’s domain name complaint.

Elliott and Gillespie argued the “indisputable fact that a majority of the relevant public uses the word ‘google’ as a verb—i.e., by saying ‘I googled it,’ and … verb use constitutes generic use.”

The court reviewed the history of genericide under trademark law and applied a test of whether the relevant public understands a mark as describing where a product comes from, or what a product is.  Put another way, if a word still describes where the product comes from, then the term is still valid as a trademark.  But if consuming public understands the word to have become the product itself (and not the producer of the product), then the mark slips into being a generic term. Escalator is another example. It became synonymous with a moving staircase product, rather than distinctive of the Otis Elevator Company as the producer of that product.

In Google’s case, the court  asserted that verb use (the use of the mark as a verb instead of an adjective) does not automatically result in a finding of genericness. The court also noted that a claim of genericide must relate to a particular type of product or service. “In order to show that there is no efficient alternative for the word “google†as a generic term,” the court argued, “Elliott must show that there is no way to describe ‘internet search engines’ without calling them ‘googles.’ Because not a single competitor calls its search engine ‘a google,’ and because members of the consuming public recognize and refer to different ‘internet search engines,’ Elliott has not shown that there is no available substitute for the word ‘google’ as a generic term.”

Compare this to the case of Q-TIPS which concluded that “medical swab” and “cotton-tipped applicator” are efficient alternatives for the brand Q-TIPS, whereas a US case involving the ASPIRIN mark concluded that, at the time, there was no efficient substitute for the term “aspirin†because consumers did not know the term “acetylsalicylic acidâ€, so they used “aspirin” in a generic sense.  Interestingly, the brand ASPIRIN remains a registered mark in Canada, although Bayer lost its trademark rights to genericide in the US.

Google survived the genericide test this time. To keep track of future attempts to challenge Google’s trademark rights, please conduct an internet search using a GOOGLE® brand search engine.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsVCC vs. VCC: Where’s the Confusion?

.

By Richard Stobbe

When we’re talking about trademarks, at which point do we measure whether there is confusion in the mind of the consumer?

We reviewed this issue in 2015 (See: No copyright or trademark protection for metatags). In that earlier decision, Vancouver Community College sued a rival college for trademark infringement, on the basis of the rival college using “VCC†as part of a search-engine optimization and keyword advertising strategy. The court in that case said: “The authorities on passing off provide that it is the ‘first impression’ of the searcher at which the potential for confusion arises which may lead to liability. In my opinion, the ‘first impression’ cannot arise on a Google AdWords search at an earlier time than when the searcher reaches a website.â€Â In other words, it is the point at which a searcher reaches the website when this “first impression†is gauged. Where the website is clearly identified without the use of any of the competitor’s trademarks, then there will be no confusion. That was then.

That decision was appealed and reversed in Vancouver Community College v. Vancouver Career College (Burnaby) Inc., 2017 BCCA 41 (CanLII). The BC Court of Appeal decided that the moment for assessing confusion is not when the searcher lands on the ‘destination’ website, but rather when the searcher first encounters the search results on the search page.  This comes from an analysis of the Trade-marks Act (Section 6) which says confusion occurs where “the use of the first mentioned trade-mark … would cause confusion with the last mentioned trade-mark.”

And it draws upon the mythical consumer or searcher – the “casual consumer somewhat in a hurry“. The BC court reinforced that “the test to be applied is a matter of first impression in the mind of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry”, and as applied to the internet search context, this occurs when the searcher sees the initial search results.

To borrow a few phrases from other cases, trade-marks have a particular function: they provide a “shortcut to get consumers to where they want to goâ€Â and “Leading consumers astray in this way is one of the evils that trade-mark law seeks to remedy.” (As quoted in the VCC case at paragraph 68).  Putting this another way, the ‘evil’ of leading casual consumers astray occurs when the consumer sees the search results displaying the confusing marks.

On the subject of whether bidding on keywords constitutes an infringement of trademarks or passing-off, the court was clear: “More significantly, the critical factor in the confusion component is the message communicated by the defendant. Merely bidding on words, by itself, is not delivery of a message. What is key is how the defendant has presented itself, and in this the fact of bidding on a keyword is not sufficient to amount to a component of passing off…” (Paragraph 72, emphasis added).

The BC Court issued a permanent injunction against Vancouver Career College, restraining them from use of the mark “VCC†and the term “VCCollege†in connection with its internet presence.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments“Place of origin” as a trademark in Canada

By Richard Stobbe

The Canadian trademarks office has released a Practice Notice in order to clarify current practice with respect to applying the descriptiveness analysis to geographical names.

In our earlier post on this topic (Trademark Series: Can a Geographical Name be a Trademark?), we noted that a geographical name can be registrable as a trademark in Canada. The issue is whether the term is “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive†in the English or French languages of the place of origin of the goods or services.

The Practice Notice tells us that a trademark will be considered a “geographic name” if the examiner’s research shows “that the trademark has no meaning other than as a geographic name.” It’s unclear what this research would consist of. (A search in Google Maps? An atlas?)

Even if the mark does have other meanings, other than as a place name, the mark will be still considered a geographical name if the trademark “has a primary or predominant meaning as a geographic name. The primary or predominant meaning is to be determined from the perspective of the ordinary Canadian consumer of the associated goods or services. If a trademark is determined to be a geographic name, the actual place of origin of the associated goods or services will be ascertained by way of confirmation provided by the applicant.” (Emphasis added)

In some case, the “actual origin” of products may be easy to determine – where, for example, apples are grown in British Columbia, then it stands to reason that “British Columbia” would be clearly descriptive of the place of origin and thus clearly descriptive of the goods. Apples are likely to be grown and harvested in one location. But how would one determine the “actual origin” of, say, a laptop which is designed in California, with parts from Taiwan and China, assembled in Thailand?

If the examiner decides that the geographic name is the same as the actual place of origin of the products, the trademark will be considered “clearly descriptive” and unregistrable. If the geographic name is NOT the same as the actual place of origin of the goods and services, the trademark will be considered “deceptively misdescriptive” since the ordinary consumer would be misled into the belief that the products originated from the location of that geographic name.

It’s worth noting that the place of origin of the products is not the same as the address of the applicant. The applicant’s head office is irrelevant for these purposes.

Need assistance navigating this area? Contact experienced trademark counsel.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsUse of a Trademark on Software in Canada

.

By Richard Stobbe

Xylem Water Solutions is the owner of the registered Canadian trademark AQUAVIEW in association with software for water treatment plants and pump stations. Â Xylem received a Section 45 notice from a trademark lawyer, probably on behalf of an anonymous competitor of Xylem, or an anonymous party who wanted to claim the mark AQUAVIEW for themselves. This is a common tactic to challenge, and perhaps knock-out, a competitor’s mark.

A Section 45 notice under the Trade-marks Act requires the owner of a registered trademark to prove that the mark has been used in Canada during the three-year period immediately before the notice date. As readers of ipblog.ca will know, the term “use” has a special meaning in trademark law. In this case, Xylem was put to the task of showing “use” of the mark AQUAVIEW in association with software.

How does a software vendor show “use” of a trademark on software in Canada?

The Act tells us that “A trade-mark is deemed to be used in association with goods if, at the time of the transfer of the property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade, it is marked on the goods themselves or on the packages in which they are distributed…” (Section 4)

The general rule is that a trademark should be displayed at the point of sale (See: our earlier post on Scott Paper v. Georgia Pacific). In that case, involving a toilet paper trademark, Georgia-Pacific’s mark had not developed any reputation since it was not visible until after the packaging was opened. As we noted in our earlier post, if a mark is not visible at the point of purchase, it can’t function as a trade-mark, regardless of how many times consumers saw the mark after they opened the packaging to use the product.

The decision in Ashenmil v Xylem Water Solutions AB, 2016 TMOB 155 (CanLII),  tackles this problem as it relates to software sales. In some ways, Xylem faced a similar problem to the one which faced Georgia-Pacific. The evidence showed that the AQUAVIEW mark was displayed on website screenshots, technical specifications, and screenshots from the software.

The decision frames the problem this way: “…even if the Mark did appear onscreen during operation of the software, it would have been seen by the user only after the purchaser had acquired the software. Â … seeing a mark displayed, when the software is operating without proof of the mark having been used at the time of the transfer of possession of the ware, is not use of the mark” as required by the Act.

The decision ultimately accepted this evidence of use and upheld the registration of the AQUAVIEW mark. It’s worth noting the following take-aways from the decision:

- The display of a mark within the actual software would be viewed by customers only after transfer of the software. Â This kind of display might constitute use of the mark in cases where a customer renews its license, but is unlikely to suffice as evidence of use for new customers.

- In this case, the software was “complicated” software for water treatment plants. The owner sold only four licenses in Canada within a three-year period.  In light of this, it was reasonable to infer that purchasers would take their time in making a decision and would have reviewed the technical documentation prior to purchase.  Thus, the display of the mark on technical documentation was accepted as “use” prior to the purchase. This would not be the case for, say, a 99¢ mobile app or off-the-shelf consumer software where technical documentation is unlikely to be reviewed prior to purchase.

- Website screenshots and digital marketing brochures which clearly display the mark can bolster the evidence of use. Again, depending on the software, purchasers can be expected to review such materials prior to purchase.

- Software companies are well advised to ensure that their marks are clearly displayed on materials that the purchaser sees prior to purchase, which will differ depending on the type of software. The display of a mark on software screenshots is not discouraged; but it should not be the only evidence of use. If software is downloadable, then the mark should be clearly displayed to the purchaser at the point of checkout.

- The cases have shown some flexibility to determine each case on its facts, but don’t rely on the mercy of the court: software vendors should ensure that they have strong evidence of actual use of the mark prior to purchase. Clear evidence may even prevent a section 45 challenge in the first place.

To discuss protection for your software and trademarks, Â contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTrader Joe’s vs. Irate Joe’s

By Richard Stobbe

In a long-running battle between Trader Joe’s and _Irate Joe’s (formerly Pirate Joe’s, a purveyor of genuine Trader Joe’s products in Vancouver, B.C.), the US Circuit Court of Appeals recently weighed in. We originally covered this story a few years ago.

In Trader Joe’s Company v. Hallatt, an individual, dba Pirate Joe’s, aka Transilvania Trading [PDF], the court considered the extraterritorial reach of US trademarks laws. The Defendant, Michael Hallatt, didn’t deny that he purchased Trader Joe’s-branded groceries in Washington state, smuggled this contraband across the border, and then resold it in a store called “Pirate Joe’s” (although Hallatt later dropped the “P” to express his frustration with TJ’s). Trader Joe’s sued in U.S. federal court for trademark infringement and unfair competition under both the federal Lanham Act and Washington state law. Since Mr. Hallatt’s allegedly infringing activity took place entirely in Canada, the question was whether U.S. federal trademarks law would extend to provide a remedy in a U.S. Court.

In the wake of this decision, Trader Joe’s federal claims are kept alive, although the court dismissed the state law claims against Hallatt.

The court concluded: “We resolve two questions to decide whether the Lanham Act reaches Hallatt’s allegedly infringing conduct, much of which occurred in Canada: First, is the extraterritorial application of the Lanham Act an issue that implicates federal courts’ subject-matter jurisdiction? Second, did Trader Joe’s allege that Hallatt’s conduct impacted American commerce in a manner sufficient to invoke the Lanham Act’s protections? Because we answer “no†to the first question but “yes†to the second, we reverse the district court’s dismissal of the federal claims and remand for further proceedings.”

In plain English, the appeals court has asked the lower court to reconsider the federal claims and make a final decision. Grab a bag of Trader Joe’s Pita Crisps with Cranberries & Pumpkin Seeds … and stay tuned!

Calgary – 08:00 MST

No comments

Happy Birthday… in Trademarks

ipbog.ca turns 10 this month. It’s been a decade since our first post in October 2006 and to commemorate this milestone …since no-one else will… let’s have a look at IP rights and birthdays.

You may have heard that the lyrics and music to the song “Happy Birthday” were the subject of a protracted copyright battle. The lawsuit came as a surprise to many people, considering this is the “world’s most popular song” (apparently beating out Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven, but that’s another copyright story for another time).  Warner Music Group claimed that they owned the copyright to “Happy Birthday”, and when the song was used for commercial purposes (movies, TV shows, commercials), Warner Music extracted license fees, to the tune of $2 million each year. When this copyright claim was finally challenged, a US court ruled that Warner Music did not hold valid copyright, resulting in a $14 million settlement of the decades-old dispute in 2016.

In the realm of trademarks, a number of Canadian trademark owners lay claim to HAPPY BIRTHDAY including:

- The Section 9 Official Mark below, depicting a skunk or possibly a squirrel with a top hat, to celebrate Toronto’s sesquicentennial. Hey, don’t be too hard on Toronto, it was the ’80s.

- Another Section 9 Official Mark, the more staid “HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986” to celebrate that city’s centennial. Because nothing says ‘let’s party’ like the words HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986.

- Cartier’s marks HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA511885 and TMA779496) in association with handbags, eyeglasses and pens.

- Mattel’s mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA221857) in association with dolls and doll clothing.

- The mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY VINEYARDS (pending) for wine, not to be confused with BIRTHDAY CAKE VINEYARDS (also pending) also for wine.

- FTD’s marks BIRTHDAY PARTY (TMA229547) and HAPPY BIRTHTEA! (TMA484760) for “live cut floral arrangements”

- And for those who can’t wait until their full birthday there’s the registered mark HALFYBIRTHDAYÂ Â (TMA833899 and TMA819609) for greeting cards and software.

- The registered mark BIRTHDAY BLISS (TMA825157) for “study programs in the field of spiritual and religious development”.

- Let’s not forget BIRTHDAYTOWN (TMA876458) for novelty items such as “key chains, crests and badges, flags, pennants, photos, postcards, photo albums, drinking glasses and tumblers, mugs, posters, pens, pencils, stick pins, window decals and stickers”.

- Of course, no trademark list would be complete without including McDonald’s MCBIRTHDAY mark (TMA389326) for restaurant services.

So, pop open a bottle of branded wine and enjoy some live cut floral arrangements and a McBirthday® burger as you peruse a decade’s worth of Canadian IP law commentary.

Calgary – 10:00 MST