Click-Through Agreements

.

By Richard Stobbe

Sierra Trading Post is an Internet retailer of brand-name outdoor gear, family apparel, footwear, sporting goods. Sierra lists comparison prices on its site to show consumers that its goods are competitively priced.

Chen, the plaintiff, sued Sierra, claiming the website’s comparison prices were false, deceptive, or misleading. The internet retailer defended by asserting that the lawsuit should be dismissed: Sierra pointed out that users of its site agreed to binding arbitration in the Terms of Use. Chen countered, arguing that he had never seen the Terms of Use and so they were not binding.

In Chen v. Sierra Trading Post, Inc., 2019 WL 3564659 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 6, 2019), a US court decision, the court reviewed the issues. There was no disagreement that the choice-of-law and arbitration clauses appeared in the Terms of Use. The question, as with so many of these cases, is around the set-up of Sierra’s check-out screen. Were the Terms of Use brought to the attention of the user, so that the user consented to those terms at the point of purchase, thus evidencing a mutual agreement between the parties to be bound by those terms?

Both Canadian and US cases have been tolerant of a range of possibilities for a check-out procedure, and the placement of “click-through” terms. This applies equally to e-commerce sites, software licensing, subscription services, or online waivers. Ideally, the terms are made available for the user to read at the point of checkout, and the user or consumer has a clear opportunity to indicate assent to those terms. In some cases, the courts have accepted terms that are linked, where assent is indicated by a check-box.

While there is no specific bright-line test, the idea is to make it as easy as possible for a consumer to know (1) that there are terms and (2) that they are taking a positive step to agree to those terms.

In this case, STP claimed that Chen would have had notice of the Terms of Use via the website’s “Checkout†page where, a few lines below the “Place my order†button, a line says “By placing your order you agree to our Terms & Privacy Policyâ€. The court noted that “The Consent line contains hyperlinks to STP’s TOU and Privacy Policy.”

On balance, the court agreed to uphold the Terms of Use and compel arbitration. While this was a win for Sierra, the click-through process could easily have been much more robust. For example, rather than “Place my order”, the checkout button could have said said “By Placing my order I agree to the Terms of Use” or a separate radio button could have been placed beside the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy to indicate assent.

Internet retailers, online service providers, software vendors and anyone imposing terms through click-through contracts should ensure that their check-out process is reviewed: make it as easy as possible for a court to agree that those terms are binding.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCanadian Smart Contract Law: Is it broke and do we need to fix it?

.

By Richard Stobbe

The idea of a ‘smart contract’ has been a lot of things: it’s upheld as the next big thing, a beacon of change for society, a nail in the coffin of an inefficient legal services profession, and it’s criticized as a misnomer for ‘dumb code’. Our review of smart contracts continues with this question: Are ‘smart contracts’ in need of specific laws and regulations in Canada?

In other words, is ‘smart contract’ law broken and in need of fixing?

(Need a quick primer on smart contracts? Can Smart Contracts Really be Smart?)

For those who may recall, the advent of other technologies has caused similar hand-wringing. For example the courts have, over the years, dealt with contract formation involving the telephone, radio, telex and fax … and email … yes, and the formation of contracts by tapping “I accept” on a screen.

There is a very good argument that the existing electronic transactions laws in Canada adequately cover the most common situations where so-called ‘smart contracts’ would be used in commercial relationships. For example, the Alberta Electronic Transactions Act (a piece of legislation that was introduced almost 20 years ago, when people talked about the “information superhighway”), was intentionally designed to be technology neutral.

The term “electronic signature†is defined in that law as “electronic information that a person creates or adopts in order to sign a record and that is in, attached to or associated with the record”. It’s so broad that the term can arguably apply to any number of possible applications, including situations where someone approves a transactional step within a smart contract work flow. Of course, this still has to be tested in court, where a judge would apply the law in an assessment of the specific facts of a particular dispute.

Does that create uncertainty? Yes, to a degree.

But the risks associated with that approach are preferable to the alternative. The alternative is to go the way of Arkansas, or other jurisdictions who have decided to wade in by prescriptively defining “smart contracts”.  For example, a 2019 law in Arkansas – “An Act Concerning Blockchain Technology†HB 1944 – amends that state’s electronic transactions law by defining “blockchain distributed ledger technology,†“blockchain technology†and “smart contract.â€Â By imposing specific definitions, these laws may have the unintended effect of excluding certain technologies that should be included, or catching use cases that were not intended to be caught. This would be the equivalent of trying, in 2001, to define an electronic transaction by looking at Amazon’s 1-click checkout. Sure, it was innovative at that time, but to peg a legal definition to that technology would have been short-sighted and unnecessarily constraining.

A second problem is a lack of standardization or uniformity in how different jurisdictions are choosing to define these technologies. This creates more uncertainty than a reliance on existing electronic transactions laws.

As blockchain and smart contract technology develops, the rush to have legal definitions cast in stone is premature and unwarranted.

Related Reading:

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsThe law in Canada on internet contracts: Part 2

.

By Richard Stobbe

Go-karting in Saskatchewan as an internet law case? Yes, and you’ll see why. In Quilichini v Wilson’s Greenhouse, 2017 SKQB 10 (CanLII), a go-kart participant is injured and sues the service provider. The service provider holds up the waiver as a complete defence, saying it contains a release of all claims.

In this case, the waiver is  provided to all participants through a kiosk system, where an electronic waiver is presented in a series of electronic pages on a computer screen. Participants have to click “next†to move from one page to the next; and finally click the “I agree†button on the electronic waiver before they can participate in the activity.

Variations of this happen everyday across Canada when users click “I agree”, “I accept” or some variation of a click, tap or swipe to indicate assent to a set of terms.

- Can legally binding contracts be formed in this way?

- And another question, even if it works for common-place transactions like a shopping-cart check-out, does it work for something as important as a release and waiver of the right to sue for personal injury?

The answer is a clear yes, according to the facts of this case. The judge in Quilichini had no trouble finding that the participant’s electronic agreement was just as effective as a signed hard-copy of the agreement. The participant had a full opportunity to read the waiver, and there was nothing obscure in the presentation of the waiver, or the choice whether or not to accept it. The court concluded: “there can be no question but that when the plaintiff clicked ‘I agree’, he was intending to accept and assume responsibility for any possible risk involved and knew he was agreeing to discharge or release the defendants from all claims or liabilities arising, in any way, from his participation.”

This conclusion is based in part on Canadian provincial laws such as Alberta’s Electronic Transactions Act, SA 2001, c E-5.5, (there’s an equivalent in Saskatchewan and other provinces), which generally indicate that if there is a legal requirement that a record be signed, that requirement is satisfied by an electronic signature. There are exceptions of course, such as wills or transfers of land.

In the Quilichini decision, the court didn’t look outside the Saskatchewan Electronic Information and Documents Act, 2000. But there are other authorities to support the proposition that binding contracts can be formed online in a number of ways. Decisions such as Kanitz v. Rogers Cable Inc., 2002 CanLII 49415 (ON SC), even deal with passive assent, where a user is deemed to be bound by something even absent a formal “click-through” button. Kanitz dealt with the question of whether internet service subscribers were bound by a subscription agreement, where that agreement was amended, then merely posted to the service provider’s site, rather than requiring a new signature or a fresh “click-through”. The subscribers were bound by the terms merely by continuing to use the service after the amended terms were posted.

In considering this, the Court in Kanitz said: “…we are dealing in this case with a different mode of doing business than has heretofore been generally considered by the courts. [remember… this was 2002] We are here dealing with people who wish to avail themselves of an electronic environment and the electronic services that are available through it. It does not seem unreasonable for persons who are seeking electronic access to all manner of goods, services and products, along with information, communication, entertainment and other resources, to have the legal attributes of their relationship with the very entity that is providing such electronic access, defined and communicated to them through that electronic format. I conclude, therefore, that there was adequate notice given to customers of the changes to the user agreement which then bound the plaintiffs when they continued to use the defendant’s service.” [Emphasis added]

This is not to say that ALL electronic contracts are always enforceable, or that all amendments will be enforceable even without a proper mechanism to collect the consent of users. However, it does provide a measure of confidence for Canadian internet business, that the underlying legal foundation will support the enforceability of contractual relationships when business is conducted online.

Want to review your own internet agreements and electronic contracting workflows to ensure they are binding and enforceable? Contact Richard Stobbe.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsWhat’s the current state of the law in Canada on internet contracts?

.

E-commerce Legal Review (Part 1): Uber’s Arbitration Clause Struck Down

By Richard Stobbe

Today we start a three-part series reviewing e-commerce agreements, click-through agreements, and online ‘terms of service’ or ‘terms of use’. Users agree to these terms every day.  What’s the current state of the law in Canada on internet contracts? Â

Almost a year ago, we wrote about a case where Uber drivers challenged Uber’s user online terms.  (See: Uber vs. Drivers: Canadian Court Upholds App Terms). Uber drivers claimed that they should have the benefit of local laws which protect employees. This case was at the centre of the debate about whether Uber’s drivers are customers, independent contractors, or employees. Uber’s counter argument was that the drivers’ claim should not proceed because, under the terms of use, all of the drivers agreed to settle disputes by arbitration in the Netherlands.

So the court had to wrestle with this question:  Should the arbitration clause in the terms of use be upheld? Or should the drivers be entitled to have their day in court in Canada?Â

The original class-action case was decided in favour of Uber. The court upheld the app terms of service, and deferred this dispute to an arbitrator in the Netherlands. The court applied the Supreme Court of Canada reasoning in Seidel v. TELUS Communications Inc. (applying the competence-competence analysis). The first Heller decision was appealed.

In the second Heller decision ( Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2019 ONCA 1 (CanLII)), the Ontario Court of Appeal struck down Uber’s mandatory arbitration clause for several reasons:

- The arbitration clause was found to be invalid on the basis of unconscionability. On this point, the court noted that the cost to initiate the mandatory arbitration process under Uber’s terms would cost a driver more than USD$14,000 (noting that the average Uber driver might earn $400 – $600 per week ).

- The court agreed that if the arbitration clause was valid, then the claim would fall within that clause. However, the court said this case fell one step prior to that: the validity of the arbitration clause itself was in issue. In that light, the competence-competence principle had no application to this case. The arbitration clause was not valid, the court decided, therefore the jurisdiction issue did not even arise.

- The court reasoned that employers (with Uber standing in the position of employer for these purposes) should not be entitled to contract out of the Employment Standards Act (ESA) on behalf of their employees. The choice to proceed by way of arbitration should be in the hands of the employee. “It is [the employee’s] choice whether to take that route,” said the Court, “and he is only barred from making a complaint if he chooses to take it. The Arbitration Clause essentially transfers that choice to Uber who then forces the appellant (and all other drivers) out of the complaints process.”

- The court raised a number of public policy considerations – including the problems regarding the result that would come out of the arbitration process in the Netherlands, the problems associated with an arbitration ruling that would not benefit others for a determination of the underlying issues. In other words, other drivers in the class would be deprived of a remedy if each driver was forced through arbitration, whereas a complaint under the Ontario Employment Standards Act would set a precedent that others could rely on. “The issue of whether persons, in the position of the appellant, are properly considered independent contractors or employees is an important issue for all persons in Ontario,” said the Court. “The issue of whether such persons are entitled to the protections of the ESA is equally important. Like the privacy issue raised in Douez, the characterization of these persons as independent contractors or employees for the purposes of Ontario law is an issue that ought to be determined by a court in Ontario.”

In the final result, the Court concluded that the mandatory arbitration clause amounted to an illegal contracting out of an employment standard, contrary to the Employment Standards Act (Ontario), assuming the drivers are indeed employees. Separately, the Court decided the arbitration clause was unconscionable at common law, and therefore invalid under the (Ontario) Arbitration Act.

Lessons for business?

- The court of appeal sent a clear message that expensive and unwieldy mandatory arbitration clauses such as the one used by Uber will risk being struck down for unconcsionability.

- Aside from the issue of unconscionability, such clauses are at risk on other public policy  grounds, where local courts wish to assert local laws. In this case, it was the ESA. Courts have shown themselves to be wary of permitting platform providers (such as Uber and Facebook) to use the terms of service to contract out of local laws. See Douez v. Facebook, Inc., [2017] 1 SCR 751, 2017 SCC 33 (CanLII), where the SCC found that Facebook’s forum selection clause was unenforceable, although for a set of confusing reasons (the majority in Douez did not address the issue of unconscionability). In Douez, it was a local privacy law that was at issue (British Columbia’s Privacy Act).

Get advice on your online contracts to ensure that they will not be at risk of being struck down based on this latest guidance from the Court.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsUber vs. Drivers: Canadian Court Upholds App Terms

.

By Richard Stobbe

One of Uber’s drivers, an Ontario resident named David Heller, sued Uber under a class action claim seeking $400 million in damages. What did poor Uber do to deserve this? According to the claim, drivers should be considered employees of Uber and entitled to the benefits of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act (See: Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2018 ONSC 718 (CanLII)).

As the court phrased it, while “millions of businesses and persons use Uber’s software Apps, there is a fierce debate about whether the users are customers, independent contractors, or employees.” If all of the drivers are to be treated as employees, the costs to Uber would skyrocket. Uber, of course, resisted this lawsuit, arguing that according to the app terms of service, the drivers actually enter into an agreement with Uber B.V., an entity incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands. By clicking or tapping “I agree” in the app terms of service, the drivers also accept a certain dispute resolution clause: by contract, the parties pick arbitration in Amsterdam to resolve any disputes.

Really, at this stage Uber’s defence was not to say “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers are independent contractors, not employees”. Rather, Uber argued that “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers agreed to settle disputes with us by arbitration in the Netherlands.”

So the court had to wrestle with this question:  Should the dispute resolution clause in the click-through terms be upheld? Or should the drivers be entitled to have their day in court in Canada?Â

The law in this area is very interesting and frankly, a bit muddled. This is because there are two distinct issues in this legal thicket: a forum-selection clause (the laws of the Netherlands govern any interpretation of the agreement), and a dispute resolution clause (here, arbitration is the parties’ chosen method to resolve any disputes under the agreement). For these two different issues, Canadian courts have applied different tests to determine whether such clauses should be upheld:

- In the case of forum selection clause, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) tells us that the rule from Z.I. Pompey Industries is that a forum selection clause should be enforced unless there is “strong cause†not to enforce it.  In the context of a consumer contract (as opposed to a “commercial agreement”), the SCC says there may be strong reasons to refrain from enforcing a forum selection clause (such as unequal bargaining power between the parties, the convenience and expense of litigation in another jurisdiction, public policy reasons, and the interests of justice). In the commercial context (as opposed to a consumer agreement), forum selection clauses are generally upheld.

- In the case of upholding arbitration clauses, the courts have applied a different analysis: arbitration is generally favoured as a means to settle disputes, using the “competence-competence principle”. Again, it’s an SCC decision that gives us guidance on this: unless there is clear legislative language to the contrary, or the dispute falls outside the scope of the arbitration agreement, courts must enforce arbitration agreements.

The court said this case “is not about a discretionary court jurisdiction where there is a forum selection clause to refuse to stay proceedings where a strong cause might justify refusing a stay; rather, it is about a very strong legislative direction under the Arbitration Act, 1991 or the International Commercial Arbitration Act, 2017 and numerous cases that hold that courts should only refuse a reference to arbitration if it is clear that the dispute falls outside the arbitration agreement.”

Applying the competence-competence analysis, the court (in my view) properly ruled in favour of Uber, upheld the app terms of service, and deferred this dispute to the arbitrator in the Netherlands. This class action, as a result, must hit the brakes.

The decision is reportedly under appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentA Software Vendor and its Customer: “like ships passing on a foggy nightâ€

By Richard Stobbe

When a customer got into a dispute with the software vendor about the license fees, the resulting case reads like a cautionary tale about software licensing. In ProPurchaser.com Inc. v. Wifidelity Inc., 2017 ONSC 7307 (CanLII), the court reviewed a dispute about a Software License Agreement. The customer, ProPurchaser, signed a license agreement with Wifidelity for the license of certain custom software at a rate of $6,000 per month. Over time, this fee increased and at the time the dispute commenced in 2017, ProPurchaser was paying a monthly fee of about $42,000.  The customer paid this fee, but apparently had no way of telling what it was paying for.

Detailed invoices were never submitted and so it was impossible to tell objectively how this fee should be broken down between license fees, support fees, expenses, or commissions.  The customer had formed the impression that this increase was due to support fees at an hourly rate, since the original license of $6,000 per month remained in effect and had never been amended in writing.

The software vendor, on the other hand, gave evidence that the license fee had increased under a verbal agreement between the parties.  “Based on the conflicting evidence,†the court mused, “it seems that the parties, much like ships passing on a foggy night, proceeded for several years unaware of the other’s different understanding about what was being charged by Wifidelity and paid for by ProPurchaser.â€

Under the Software License, either party was entitled to terminate without cause, by providing 14 days’ written notice to the other party. Eventually, the software vendor, Wifidelity, exercised the right of termination, triggering the lawsuit. ProPurchaser immediately sought a court order preserving the status quo, to prevent the software vendor from shutting down the software. In August, the court granted that order for a period of six months, subject to continuing payment of the $42,000 monthly license fee by ProPurchaser.  In November, ProPurchaser again approached the court, this time for an order extending the order until trial. Such an order could, in effect, be tantamount to a final resolution of the dispute, forcing the license to remain in effect. However, this would fly in the face of the clear terms of the agreement, which permitted for termination on 14 days’ notice.

While the dispute has yet to go to trial, there are some interesting lessons for software vendors and licensees:

- From a legal perspective, in order to succeed in its injunction application, ProPurchaser had to convince the court that termination of the license caused “irreparable harmâ€. However, the agreement itself allowed each party to terminate for no reason on very short notice, making it difficult to argue that this outcome – one that both sides had agreed to – would cause harm. If it caused so much harm, why did ProPurchaser agree to it in the first place? And in any event, any harm was compensable in damages and therefore not “irreparableâ€.

- That was a problem for the customer, when making a fairly narrow legal argument, but it’s also a problem from a business perspective. If the licensed software supports mission-critical functions within the licensee’s business, then make sure it’s not terminable for convenience by the software vendor.

- If changes are made to the software license agreement, particularly regarding the essential business terms like license fees and support fees, make sure these amendments are captured in writing, through a revised pricing schedule, or detailed invoicing that has been accepted by both sides.

Calgary – 13:00Â MST

No comments

Use of a Trademark on Software in Canada

.

By Richard Stobbe

Xylem Water Solutions is the owner of the registered Canadian trademark AQUAVIEW in association with software for water treatment plants and pump stations. Â Xylem received a Section 45 notice from a trademark lawyer, probably on behalf of an anonymous competitor of Xylem, or an anonymous party who wanted to claim the mark AQUAVIEW for themselves. This is a common tactic to challenge, and perhaps knock-out, a competitor’s mark.

A Section 45 notice under the Trade-marks Act requires the owner of a registered trademark to prove that the mark has been used in Canada during the three-year period immediately before the notice date. As readers of ipblog.ca will know, the term “use” has a special meaning in trademark law. In this case, Xylem was put to the task of showing “use” of the mark AQUAVIEW in association with software.

How does a software vendor show “use” of a trademark on software in Canada?

The Act tells us that “A trade-mark is deemed to be used in association with goods if, at the time of the transfer of the property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade, it is marked on the goods themselves or on the packages in which they are distributed…” (Section 4)

The general rule is that a trademark should be displayed at the point of sale (See: our earlier post on Scott Paper v. Georgia Pacific). In that case, involving a toilet paper trademark, Georgia-Pacific’s mark had not developed any reputation since it was not visible until after the packaging was opened. As we noted in our earlier post, if a mark is not visible at the point of purchase, it can’t function as a trade-mark, regardless of how many times consumers saw the mark after they opened the packaging to use the product.

The decision in Ashenmil v Xylem Water Solutions AB, 2016 TMOB 155 (CanLII),  tackles this problem as it relates to software sales. In some ways, Xylem faced a similar problem to the one which faced Georgia-Pacific. The evidence showed that the AQUAVIEW mark was displayed on website screenshots, technical specifications, and screenshots from the software.

The decision frames the problem this way: “…even if the Mark did appear onscreen during operation of the software, it would have been seen by the user only after the purchaser had acquired the software. Â … seeing a mark displayed, when the software is operating without proof of the mark having been used at the time of the transfer of possession of the ware, is not use of the mark” as required by the Act.

The decision ultimately accepted this evidence of use and upheld the registration of the AQUAVIEW mark. It’s worth noting the following take-aways from the decision:

- The display of a mark within the actual software would be viewed by customers only after transfer of the software. Â This kind of display might constitute use of the mark in cases where a customer renews its license, but is unlikely to suffice as evidence of use for new customers.

- In this case, the software was “complicated” software for water treatment plants. The owner sold only four licenses in Canada within a three-year period.  In light of this, it was reasonable to infer that purchasers would take their time in making a decision and would have reviewed the technical documentation prior to purchase.  Thus, the display of the mark on technical documentation was accepted as “use” prior to the purchase. This would not be the case for, say, a 99¢ mobile app or off-the-shelf consumer software where technical documentation is unlikely to be reviewed prior to purchase.

- Website screenshots and digital marketing brochures which clearly display the mark can bolster the evidence of use. Again, depending on the software, purchasers can be expected to review such materials prior to purchase.

- Software companies are well advised to ensure that their marks are clearly displayed on materials that the purchaser sees prior to purchase, which will differ depending on the type of software. The display of a mark on software screenshots is not discouraged; but it should not be the only evidence of use. If software is downloadable, then the mark should be clearly displayed to the purchaser at the point of checkout.

- The cases have shown some flexibility to determine each case on its facts, but don’t rely on the mercy of the court: software vendors should ensure that they have strong evidence of actual use of the mark prior to purchase. Clear evidence may even prevent a section 45 challenge in the first place.

To discuss protection for your software and trademarks, Â contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAndroid vs. Java: Copyright Update

By Richard Stobbe

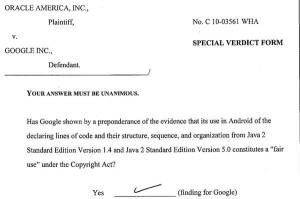

In a sprawling,  billion-dollar lawsuit that started in 2010, a jury yesterday returned a verdict in favour of Google, delivering a blow to Oracle.  (For those who have lost the thread of this story, see : API Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round).

The essence of Oracle America Inc. v. Google Inc. is a claim by Oracle that Google’s Android operating system copied a number of APIs from Oracle’s Java code, and this copying constituted copyright infringement. Infringement, Oracle argued, that should give rise to damages based on Google’s use of Android. Now think for a minute of the profits that Google might attribute to its use of Android, which has dominated mobile operating system since its introduction in 2007. Oracle claimed damages of almost $10 billion.

In prior decisions, the US Federal Court decided that Google’s copying did infringe Oracle’s copyright. The central issue in this phase was whether Google could sustain a ‘fair use’ defense to that infringement. Yesterday, the jury sided with Google, deciding that Google’s use of the copied code constituted ‘fair use’, effectively quashing Oracle’s damages claim.

Oracle reportedly vowed to appeal.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsLiability of Cloud-Based Service Provider For Data Breach

By Richard Stobbe

Silverpop Systems provides digital marketing services through a cloud-based tool called ‘Engage’. Leading Market Technologies, Inc. (“LMT”) engaged Silverpop through a service agreement and during the course of that agreement LMT uploaded digital advertising content and recipient e-mail addresses to the Engage system. A trove of nearly half a million e-mail addresses, provided by LMT, was stored on the Engage online system. In November 2010, Silverpop’s system was hacked, putting LMT’s email list at risk. Silverpop notified LMT of the data breach. After LMT refused to pay for further service, Silverpop suspended the agreement.

Litigation commenced in 2012, with LMT claiming damages for breach of contract and negligence based on Silverpop’s failure to keep the email list secure. Should the service provider be liable? Silverpop argued that it was engaged to provide access to its online system, not specifically to keep data secure. Thus there was no breach of its obligations under the agreement. And anyway, if LMT suffered any damages, they were indirect or consequential and consequential such damages were excluded under the terms of the agreement. LMT countered that, in fact, the agreement quite clearly contained a confidentiality clause, and that the damages suffered by LMT were direct damages, not indirect consequential damages.

The US Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in Silverpop Systems Inc. v. Leading Market Technologies Inc. sided with Silverpop:

- “Here, the parties’ agreement was not one for the safeguarding of the LMT List. Rather, the parties contracted for the providing of e-mail marketing services. While it was necessary for LMT to provide a list of intended recipients (represented as e-mail addresses on the LMT List) to ensure that the service Silverpop provided (targeted e-mail marketing) was carried out, the safe storage of the list was not the purpose of the agreement between the parties.” (Emphasis added)

The court was careful to review both the limit of liability clause (which provided an overall cap on liability to 12 months fees), and the exclusion clause (which barred recovery for indirect or consequential damages). The overall limit of liability had an exception: the cap did not apply to a breach of the confidentiality obligation. However, this exception did not impact the scope of the limit on indirect or consequential damages. Since the court decided that the claimed breach did not result from a failure of performance, and the consequential damages clause applied to LMT’s alleged loss. As a result, LMT’s claims were dismissed.

Lessons for business?

- Those limitation of liability and exclusion clauses are often considered “boilerplate”. But they really do make a difference in the event of a claim. Ensure you have experienced counsel providing advice when negotiating these clauses, from either the customer or service provider perspective.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsApple’s Liability for the Xcode Hack

.

By Richard Stobbe

I don’t think I’m going out on a limb by speculating that someone, somewhere is preparing a class-action suit based on the recently disclosed hack of Apple’s app ecosystem.

How did it happen? In a nutshell, hackers were able to infect a version of Apple’s Xcode software package for iOS app developers. A number of iOS developers – primarily in China, according to recent reports – downloaded this corrupted version of Xcode, then used it to compile their apps. This corrupted version was not the “official” Apple version; it was accessed from a third-party file-sharing site. Apps compiled with this version of Xcode were infected with malware known as XcodeGhost. These corrupted apps were uploaded and distributed through Apple’s Chinese App Store. In this way the XcodeGhost malware snuck past Apple’s own code review protocols and, through the wonder of app store downloads, it infected millions of iOS devices around the world.

The malware does a number of nasty things – including fishing for a user’s iCloud password.

This case provides a good case study for how risk is allocated in license agreements and terms of service. What do Apple’s terms say about this kind of thing? In Canada, the App Store Terms and Conditions govern a user’s contractual relationship with Apple for the use of the App Store. On the face of it, these terms disclaim liability for any “…LOSS, CORRUPTION, ATTACK, VIRUSES, INTERFERENCE, HACKING, OR OTHER SECURITY INTRUSION, AND APPLE CANADA DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY RELATING THERETO.”

Apple could be expected to argue that this clause deflects liability. And if Apple is found liable, then it would seek the cover of its limitation of liability clause. In the current version of the terms, Apple claims an overall limit of liability of $50. Let’s not forget that “hundreds of millions of users” are potentially affected.

As a preliminary step however, Apple would be expected to argue that the law of the State of California governs the contract, and Apple would be arguing that any remedy must be sought in a California court (see our post the other day: Forum Selection in Online Terms).

Will this limit of liability and forum-selection clause hold up to the scrutiny of Canadian courts if there is a claim against Apple?

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsForum Selection in Online Terms

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say you’re a Canadian company doing business with a US supplier – which law should govern the contract? ‘Forum selection’ and ‘governing law’ refer to the practice of choosing the applicable law and venue for resolving disputes in a contract.

Software vendors and cloud service providers often include these clauses in their standard-form contracts as a means of ensuring that they enjoy home-turf advantage in the event of disputes. This is very common in consumer-facing contracts, such as Facebook’s Terms of Service. That contract says: “e laws of the State of California will govern this Statement, as well as any claim that might arise between you and us, without regard to conflict of law provisions.”

In our earlier post (Two Privacy Class Actions: Facebook and Apple), we looked at a BC decision which reviewed the question of whether the Facebook terms (which apply California law) should be enforced in Canada or whether they should give way to local law. The lower court accepted that, on its face, the Terms of Service were valid, clear and enforceable and the lower court went on to decide that Facebook’s Forum Selection Clause should be set aside in this case, and the claim should proceed in a B.C. court.

Facebook appealed that decision: Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2015 BCCA 279 (CanLII), (See this link to the Court of Appeal decision). The appeal court reversed and decided that the Forum Selection Clause should be enforced.

Interestingly, the court said “As a matter of B.C. law, no state (including B.C.) may unilaterally arrogate exclusive adjudicative jurisdiction for itself by purporting to apply its jurisdictional rules extraterritorially.” (See the debate regarding the Google and Equustek decision for a different perspective on the extraterritorial reach of B.C. courts.)

The Douez decision was fundamentally a class-action breach of privacy claim, and that claim was stopped through the Forum Selection Clause.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

2 commentsCASL 2.0: The Computer Program Provisions (Part 3)

–

By Richard Stobbe

The CRTC has released guidelines on the implementation of the incoming computer-program provisions of Canada’s Anti-Spam Law (CASL). Software vendors should review the  CASL Requirements for Installing Computer Programs for guidance on installing software on other people’s computer systems. Remember, the start-date of January 15, 2015 is less than 2 months away. Here are a few highlights:

- CASL prohibits the installation of software to another person’s computing computer – which includes any device, laptop, smartphone, desktop, gaming console, etc.) in the course of commercial activity without express consent;

- Downloading your own app from iTunes or Google Play? CASL does not apply to software, apps or updates that are downloaded by users themselves;Â

- Maybe you still use a CD to install software? CASL does not apply to “offline” installations by a user;

- Where implied consent cannot be relied upon, then express consent is required. The guidelines state the following:

“When seeking consent for the installation you must clearly and simply set out:

- The reason you are seeking consent;

- Who is seeking consent (e.g., name of the company; or if consent is sought on behalf of another person, that person’s name);

- If consent is sought on behalf of another person, a statement indicating which person is seeking consent and which person on whose behalf consent is being sought;

- The mailing address and one other piece of contact information (i.e., telephone number, email address, or Web address);

- A statement indicating that the person whose consent is sought can withdraw their consent; and

- A description in general terms of the functions and purpose of the computer program to be installed.” Â

Â

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTwo Privacy Class Actions: Facebook and Apple (Part 2)

–

By Richard Stobbe

In Part 1, we looked at the B.C. decision in Douez v. Facebook, Inc.

Another proposed privacy class action was heard in the B.C. court a few months later: Ladas v. Apple Inc., 2014 BCSC 1821 (CanLII).

This was a claim by a representative plaintiff, Ms. Ladas, alleging that Apple breached the customer’s right to privacy under the Privacy Act (B.C.), since iOS 4 records the location of the “iDevice” (that’s the term used by the court for any Apple-branded iOS products) by surreptitiously recording and storing locational data in unencrypted form which is “accessible to Apple”. The claim did not assert that this info was transmitted to Apple, merely that it was “accessible to Apple”. This case involved a different section of the Privacy Act (B.C.) than the one claimed in Douez.

The Ladas claim, curiously, referred to a number of public-sector privacy laws as a basis for the class action, and the court dismissed these claims as providing no legal basis. The court did accept that there was a basis for a claim under the Privacy Act (B.C.) and similar legislation in 3 other provinces. However, the claim fell down on technical merit. It did not meet all of the requirements under the Class Proceedings Act: specifically, the court was not convinced that there was an “identifiable class” of 2 or more persons, and did not accept there were “common issues” among the proposed class members (assuming there was an identifiable class).

Thus, the class action was not certified. It was dismissed without leave to amend the pleadings.

Apple’s iOS software license agreement did not come into play, since the claim was dismissed on other grounds. If the claim had proceeded far enough to consider the iOS license, then it would surely have faced the same defences raised by Facebook in Douez. As the judgement noted: Apple argued that “every time a user updates the version of iOS running on the user’s iDevice, the user is prompted to decide whether the user wants to use Location Services by accepting the terms of Apple’s software licensing agreement. Apple relies on users taking such steps in its defence of the plaintiff’s claims. The legal effect of a user clicking on “consent†or “allow†or “ok†or “I agree†would be an issue on the merits in this action.”

Any test of Apple’s license agreement will have to wait for another day.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTwo Privacy Class Actions: Facebook and Apple

–

By Richard Stobbe

Two privacy class actions earlier this year have pitted technology giants Facebook Inc. and Apple Inc. against Canadian consumers who allege privacy violations. The two cases resulted in very different outcomes.

First, the Facebook decision: In Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2014 BCSC 953 (CanLII), the court looked at two basic questions:

- Do British Columbian users of social media websites run by a foreign corporation have the protection of BC’s Privacy Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 373?

- Do the online terms of use for social media override these protections?

The plaintiff Ms. Douez alleged that Facebook used the names and likenesses of Facebook customers for advertising through so-called “Sponsored Storiesâ€. The claim alleges that Facebook ran the “Sponsored Stories” program without the permission of customers, contrary to of s. 3(2) of the B.C. Privacy Act which says:

“It is a tort, actionable without proof of damage, for a person to use the name or portrait of another for the purpose of advertising or promoting the sale of, or other trading in, property or services, unless that other, or a person entitled to consent on his or her behalf, consents to the use for that purpose.”

Interestingly, this Act was first introduced in B.C. in 1968, even before the advent of the primitive internet in 1969 .

Facebook argued that its Terms of Use precluded any claim in a B.C. court, due to the “Forum Selection Clause” which compels action in the State of California. The court accepted that, on its face, the Terms of Service were valid, clear and enforceable. However, the court went on to decide that the B.C. Privacy Act establishes unique claims and specific jurisdiction. The Act mandates that claims under it “must be heard and determined by the Supreme Court†in British Columbia. This convinced the court that Facebok’s Forum Selection Clause should be set aside in this case, and the claim should proceed in a B.C. court.

The class action was certified. Facebook has appealed. Stay tuned.

Next up, the Apple experience.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCASL 2.0: The Computer Program Provisions (Part 2)

–

By Richard Stobbe

In Part 1 we looked at some basic concepts. In Part 2, we look at “enhanced disclosure” requirements.

If the computer program that is to be installed performs one or more of the functions listed below, the person who seeks express consent must disclose additional information. This disclosure must be made “clearly and prominently, and separately and apart from the licence agreement”. In this additional or enhanced disclosure, the software vendor must describe the program’s “material elements” including the nature and purpose of the program, and the impact on the user’s computer system. A software vendor must bring this info to the attention of the user. This applies if you, as the software vendor, want to install a program that does any of the following things, and causes the computer system to operate in a manner that “is contrary to the reasonable expectations of the owner”. (You have to guess at the reasonable expectations of the user.) These are the functions that the legislation is aimed at:

- collecting personal information stored on the computer system;

- interfering with the owner’s or an authorized user’s control of the computer system;

- changing or interfering with settings, preferences or commands already installed or stored on the computer system without the knowledge of the owner or an authorized user of the computer system;

- changing or interfering with data that is stored on the computer system in a manner that obstructs, interrupts or interferes with lawful access to or use of that data by the owner or an authorized user of the computer system;

- causing the computer system to communicate with another computer system, or other device, without the authorization of the owner or an authorized user of the computer system;

- installing a computer program that may be activated by a third party without the knowledge of the owner or an authorized user of the computer system.

If the computer program or app that you, as the software vendor, want to install does any of these things, then you need to comply with the enhanced disclosure obligations, as well as get express consent.

There are some exceptions: A user is considered to have given express consent if the program is

-

a cookie,

-

HTML code,

-

Java Scripts,

-

an operating system,

-

any other program that is executable only through the use of another computer program whose installation or use the person has previously expressly consented to, or

-

a program that is necessary to correct a failure in the operation of the computer system or a program installed on it and is installed solely for that purpose; AND

-

the person’s conduct is such that it is reasonable to believe that they consent to the program’s installation.

Remember: These additional provisions in CASL which deal with the installation of software come into effect on January 15, 2015, in less than 3 months. An offence under CASL can result in monetary penalties as high as $1 million for individuals and $10 million for businesses.

If you are a software vendor selling in Canada, get advice on the implications for automatic installs and updates, and how to structure consents, whether this is for business-to-business, business-to-consumer, or mobile apps. There are already more than 1,000 complaints under the anti-spam provisions of the law. You don’t want to be the test case for the computer program provisions.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCASL 2.0: The Computer Program Provisions (Part 1)

–

By Richard Stobbe

It’s mid-October. Like many businesses in Canada, you may be weary of hearing about CASL compliance. Hopefully that weariness is due to all the hard work you did 3 months ago to bring your organization into compliance for the July 1st start-date.

If you’re a software vendor, then you should gird yourself for round two: Yes, there are additional provisions in CASL which deal with the installation of software, and those rules come on stream in 3 months on January 15, 2015.

Section 8 of CASL ostensibly deals with spyware and malware. Hackers are not the only problem; think of the Sony Rootkit case (See our earlier post here) as another example of the kind of thing that this law was designed to address.

This is the essence of Section 8: “A person must not, in the course of a commercial activity, install …a computer program on any other person’s computer system… unless the person has obtained the express consent of the owner …” This applies only if the computer system is located in Canada, or if the person either is in Canada at the relevant time or is acting under the direction of a person who is in Canada at the time when they give the directions.

This relatively simple idea – get consent if you want to install an application on someone else’s system in Canada – has far-reaching implications due to the way the legislation draws the definitions of “computer program” and “computer system” from the Criminal Code. As you can guess, the Criminal Code definitions are extremely broad. So, what does this mean in real life?

- Certain types of specified programs require “enhanced disclosure” by the software vendor. (I am saying ‘software vendors’ as those are the entities most likely to bring themselves into compliance. Of course, hackers and organized crime syndicates should also take note of the enhanced disclosure requirements);

- Express consent, under this law, means that the consent must be requested clearly and simply, and the purpose of the consent must be described;

- The software vendor requesting consent must describe the function and purpose of the computer program that is to be installed;

- The software vendor requesting consent must provide an electronic address so that the user can request, within a period of one year, that the program be removed or disabled;

- Note that if a computer program is installed before January 15, 2015, then the person’s consent is implied. This implied consent lasts until the user gives notice that they don’t want the installation anymore. Or until January 15, 2018, whichever comes first. I’m not making this stuff up, that’s what the Act says.

- One more thing: Enhanced disclosure does not apply if the computer program only collects, uses or communicates “transmission data”. Transmission data is what you might call envelope information. The Act defines it as data that deals with “dialling, routing, addressing or signalling” and although it might show info like “type, direction, date, time, duration, size, origin, destination or termination of the communication”, it does not reveal “the substance, meaning or purpose of the communication”. So there is effectively a carve-out for the tracking of this category info.

Don’t worry, Canadian anti-spam laws are kind of like Lord of the Rings: Sequels will keep coming whether you like it or not. Once we’re past January 15, 2015, you can look forward to July 1, 2017, which is the day on which sections 47 to 51, 55 of CASL come into force. These provisions institute a private right of action for any breach of the Act.

If you are a software vendor selling in Canada, get advice on the implications for automatic installs and updates, whether this is for business-to-business, business-to-consumer, or mobile apps. There are already more than 1,000 complaints under the anti-spam provisions of the law. You don’t want to be the test case for the computer program provisions.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsWhat, exactly, is a browsewrap?

–

By Richard Stobbe

Browsewrap, clickwrap, clickthrough, terms of use, terms of service, EULA. Just what are we talking about and how did we get here?

In Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2014 WL 4056549 (9th Cir. Aug. 18, 2014) the US Ninth Circuit wades into the subject of online contracting. Law professor Eric Goldman (ericgoldman.org) argues that these terms we’re accustomed to using, to describe ecommerce agreements, only contribute to the confusion. The term “browsewrap” derives from “clickwrap”, which is itself a portmanteau derived from the concept of a shrinkwrap license. As one court described it in 1996: “The ‘shrinkwrap license’ gets its name from the fact that retail software packages are covered in plastic or cellophane shrink wrap, and some vendors… have written licenses that become effective as soon as the customer tears the wrapping from the package.”

The enforceability of a browsewrap – it is argued – is based not on clicking, but on merely browsing the webpage in question. However, the term browsewrap is often used in the context of an online retailer hoping to enforce its terms, in a situation where they should have used a proper click-through agreement.

In Nguyen, the court dealt with a claim by a customer who ordered HP TouchPad tablets from the Barnes & Noble site. Although the customer entered an order through the shopping cart system, Barnes & Noble later cancelled that order. The customer sued. The resulting litigation turned on the enforceability of the online terms of service (TOS). The court reviewed the placement of the TOS link and found a species of unenforceable browsewrap - the TOS link was somewhere near the checkout button, but completion of the sale was not conditional upon acceptance of the TOS.

There is a whole spectrum upon which online terms can be placed. At one end, a click-the-box agreement (in which completion of the transaction is conditional upon acceptance of the TOS) is generally considered to be valid and enforceable. At the other end, we see passive terms that are linked somewhere on the website, usually from the footer, sometimes hovering near the checkout or download button.  In Nguyen, the terms were passive and required no active step of acceptance. The court concluded that: “Where a website makes its terms of use available via a conspicuous hyperlink on every page of the website but otherwise provides no notice to users nor prompts them to take any affirmative action to demonstrate assent, even close proximity of the hyperlink to relevant buttons users must click on —without more — is insufficient…”

This leaves open the possibility that browsewrap terms (where no active step is required) could be enforceable if the user has notice (actual or constructive) of those terms.

In Canada, the concept was most recently addressed by the court in Century 21 Canada Limited Partnership v. Rogers Communications Inc., 2011 BCSC 1196 (CanLII). In that case, there was no active click-the-box terms of use, but the “browsewrap” terms were nevertheless upheld as enforceable, in light of the circumstances. Three particular factors convinced the court that it should uphold the terms: 1. the dispute did not involve a business-to-consumer dispute (as it did in Nguyen). Rather the parties were “sophisticated commercial entities”. 2. The defendants had actual notice of the terms. 3. The defendants employed similar terms on their own site.

The lessons for business?

The “browsewrap” is a passive attempt to impose terms on a site visitor or customer. Such passive terms should not be employed where the party seeking to enforce those terms requires certainty of enforceability. Even where there is a “conspicuous hyperlink” or “notice to users” or “close proximity of the hyperlink”, none of these factors should be relied upon, even if they might create an enforceable contract in special cases. Maybe it is time to retire the term “browsewrap” and replace it with “probably unenforceable”.

Now, do you still want to rely on a browsewrap agreement?

Related Reading: Online Terms – What Works, What Doesn’t

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentConfidentiality & Sealing Orders in Software Disputes

–

Two software companies wanted to integrate their software products. The relationship soured and one of the parties – McHenry – purported to terminate the Software Licensing and Development Agreement and then launched a lawsuit in the Federal Court in the US, claiming copyright infringement and breach of contract. The other party – ARAS – countered by invoking the mandatory arbitration clause in the software agreement. The US court compelled the parties to resolve their dispute through arbitration in Vancouver. After the arbitration, the arbitrator’s decision was appealed in the BC Supreme Court. In that appeal, McHenry sought a “sealing order” asking the BC court, in effect, to order confidentiality over the March 26, 2014 Arbitration Award itself. This is because ARAS, who prevailed at arbitration, circulated the arbitration award to others.

In the recent decision (McHenry Software Inc. v. ARAS 360 Incorporated, 2014 BCSC 1485 (CanLII)) the BC Supreme Court considered the law of “sealing orders” and confidentiality in the context of a dispute between two software companies.

The essence of McHenry’s complaint was that the arbitrator’s award should be treated confidentially, since it contained confidential and sensitive information about the dispute, which could harm or disadvantage McHenry in its negotiations with future software development partners.

The court reviewed the legal principles governing sealing orders. A “sealing order” is simply court-ordered confidentiality over court records or evidence. While there is a presumption in favour of public access in the Canadian justice system, there are times when it is appropriate to deny access to certain records to prevent a “serious risk to an important interest” as long as “the public interest in confidentiality outweighs the public interest in opennessâ€. (To dig deeper on this, see: Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), 2002 SCC 41 (CanLII), 2002 SCC 41.)

If you were hoping for a handy three-part test, you’re in luck:

- First, the risk in question must be real and substantial, and must pose a “serious threat” to the commercial interest in question.

- The interest must be tied to a public interest in confidentiality. The SCC said: “a private company could not argue simply that the existence of a particular contract should not be made public because to do so would cause the company to lose business, thus harming its commercial interests.” Courts must remember that a confidentiality order involves an infringement on freedom of expression, so it should not be undertaken to satisfy purely commercial interests.

- Third, the court must consider whether there are any reasonable alternatives to a confidentiality order, or look for ways to restrict the scope of the order as much as possible in the context.

Ultimately, the BC Court was not sympathetic to McHenry’s arguments for a sealing order. If McHenry was so concerned about the confidentiality of these proceedings, the court argued, then McHenry would not have launched a lawsuit against ARAS in the US Federal Court, where there is no confidentiality. In pursuing litigation, McHenry filed numerous documents in the public record, including its Arbitration Notice, its Statement of Claim in the Arbitration and its petition in the BC Court proceedings, some of which contained potentially sensitive information.

“Moreover,” the court continued, “there is no general principle that the confidentiality of arbitration proceedings carries over to court proceedings when the arbitration is appealed. On the contrary, such court proceedings are generally public.”

This case serves as a reminder of the confidentiality issues that can arise in the conext of a dispute between software companies, both in arbitration proceedings and in the litigation context. Make sure you seek experienced counsel when handling the complex issues of confidentiality, sealing orders and licensing disputes.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsAPI Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round

By Richard Stobbe

The basic question “are APIs eligible for copyright protection?” has consumed much analysis (and legal fees) during the lawsuit between Oracle and Google, which started in 2010. (For more reading on our long-running coverage of the long-running Oracle vs. Google patent and copyright litigation, see below.)

The basic premise of Oracle’s complaint against Google is that the wildly popular Android operating system copied 37 Java API packages verbatim, and inserted the code from those APIs into the Android software. This copying was done without a license from Oracle. Therefore, says Oracle, copyright infringement has occurred. In a 2012 decision, the district court decided that the Java APIs were not subject to copyright protection. Therefore, said the lower court, there was no infringement. The US Federal Court of Appeals has reversed that finding.

In a 69-page decision released on May 9, 2014, the appeal court has decided that these Java APIs are subject to copyright protection, and concluded as follows: “Because we conclude that the declaring code and the structure , sequence, and organization of the API packages are entitled to copyright protection, we reverse the district court’s copyrightability determination with instructions to reinstate the jury’s infringement finding as to the 37 Java packages . Because the jury deadlocked on fair use, we remand for further consideration of Google’s fair use defense in light of this decision.”In short, Google has infringed Oracle’s copyright, and the question to be determined now is whether Google has a “fair use” defense to that infringement.

The EFF has called the decision dangerous since it exposes software developers to copyright infringement lawsuits. However, for software vendors, it may help strengthen the controls they place on developers to maintain standards and cross-compatibility through licensing. After all, that was (in theory) one of the complaints raised by Oracle – that its “write once, run anywhere” Java principle was violated when Google mis-used the Java APIs to essentially bring Android out of compatibility with the Java platform.

Related Reading:

- API Copyright Update: Oracle & Google …and Harry Potter

- Update on Oracle vs. Google

- Copyright: Apps and APIs

- Copyright Protection for APIs

- SDKs and APIs: Do they have copyright protection?

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

1 commentPatent Infringement Lawsuits Against Software End-Users

–

Are you a Canadian software vendor with customers in the USA? Let’s say your US end-user customer is sued for patent infringement in the US based on use of your software, but the lawsuit avoids naming your company. In other words, your customers are sued, but you are not.

Ok, so you avoided a lawsuit. However, for business reasons you may want to be “in the ring” to assist your end-user customers to defend the infringement claims. One of the defences to infringement is to challenge the validity of the patent in question. But if your company is not named, how do you raise that defence? In order to seek a “declaratory judgment” that the patent is invalid, you need something called “standing” – a right to make your case in court. If you are defending an infringement allegation (if you are named in the lawsuit), you have that standing as a defendant. But if not, you have to ask the court for standing… sound complicated?

This is what happened to Microsoft, when its end-users were sued for patent infringement by Datatern. Datatern, not wanting to lock horns with Microsoft (for obvious reasons) just named the software end-users in the patent infringement lawsuit. In Microsoft Corporation v. Datatern, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2014), Microsoft sought standing to have the patents declared invalid.

The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in the US said that Microsoft does not have the “right to bring the declaratory judgment action solely because their customers have been sued for direct infringement”. To bring an invalidity declaratory judgment action against DataTern, Microsoft needed something more. The court indicated that:

- Microsoft would need to show a controversy between Microsoft and the patent holder as to Microsoft’s liability for:

- induced infringement, or

- contributory infringement,

based on the alleged acts of direct infringement by the end-user customers; or

- Microsoft would have standing if it had a contractual obligation to indemnify its customers against the infringement claim. In this case, there was no indemnity obligation.

The use of Microsoft-provided documentation by Datatern in the patent infringement lawsuit was enough to establish standing for Microsoft, since this implied that Microsoft encouraged (or “induced”) the infringing use. However, this only applied to some of the patents in question.

Wherever Datatern used third-party (non-Microsoft) documentation to evidence the alleged infringement, Microsoft was too far removed from the controversy and there was no implied assertion that Microsoft induced the infringement. Microsoft could not establish the necessary controversy between it and Datatern, the patent holder. In connection with that particular patent, Microsoft lacked standing and its declaratory judgment action to challenge the validity of the patent could not proceed.

Remember this is a US case, but Canadian software vendors should review these patent infringement issues with counsel (including the costs and benefits of IP infringement indemnity clauses) to ensure that their end-user license agreements manage the risks in light of this decision.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No comments