The Artificial Intelligence and Data Act… coming soon to AI near you

In June, 2022, the Government introduced Bill C-27, an Act to enact the Consumer Privacy Protection Act, the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act, and the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act. A major component of this proposed legislation is a brand new law on artificial intelligence. This will be, if passed, the first Canadian law to regulate AI systems.

The stated aim of the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) is to regulate international and interprovincial trade and commerce in artificial intelligence systems. The Act requires the adoption of measures to mitigate “risks of harm” and “biased output” related to something called “high-impact systems“.

Ok, so how will this work? First, the Act (since it’s federal legislation) applies to “regulated activity” which refers to specific activities carried out in the course of international or interprovincial trade and commerce. That makes sense since that’s what falls into the federal jurisdiction. Think banks and airlines, for sure, but the scope will be wider than that since any use of a system by private sector organizations to gather and process data across provincial boundaries will be caught. The regulated activities are defined as:

- (a) processing or making available for use any data relating to human activities for the purpose of designing, developing or using an artificial intelligence system;

- (b) designing, developing or making available for use an artificial intelligence system or managing its operations.

That is a purposely broad definition which is designed to catch both the companies that use these systems, and providers of such systems, as well as data processors who deploy AI systems in the course of data processing, where such systems are used in the course of international or interprovincial trade and commerce.

The term “artificial intelligence system” is also broadly defined and captures any “technological system that, autonomously or partly autonomously, processes data related to human activities through the use of a genetic algorithm, a neural network, machine learning or another technique in order to generate content or make decisions, recommendations or predictions.”

For anyone carrying out a “regulated activity” in general, there are record keeping obligations, and regulations regarding the handling of anonymized data that is used in the course of such activities.

For those who are responsible for so-called “high-impact systems“, there are special requirements. First, a provider or user of such a system is responsible to determine if their system qualifies as a “high-impact system” under AIDA (something to be defined in the regulations).

Those responsible for such “high-impact systems” must, in accordance with the regulations, establish measures to identify, assess and mitigate the risks of harm or biased output that could result from the use of the system, and they must also monitor compliance with these mitigation measures.

There’s more: anyone who makes a “high-impact system” available, or who manages the operation of such a system, must also publish a plain-language description of the system that includes an explanation of:

- (a) how the system is intended to be used;

- (b) the types of content that it is intended to generate and the decisions, recommendations or predictions that it is intended to make; and

- (c) the mitigation measures.

- (d) Oh, and any other information that may be prescribed by regulation in the future.

The AIDA sets up an analysis of “harm” which is defined as:

- physical or psychological harm to an individual;

- damage to an individual’s property; or

- economic loss to an individual.

If there is a risk of material harm, then those using these “high-impact systems” must notify the Minister. From here, the Minister has order-making powers to:

- Order the production of records

- Conduct audits

- Compel any organization responsible for a high-impact system to cease using it, if there are reasonable grounds to believe the use of the system gives rise to a “serious risk of imminent harm”.

The Act has other enforcement tools available, including penalties of up to 3% of global revenue for the offender, or $10 million, and higher penalties for more serious offences, up to $25 million.

If you’re keeping track, the Act requires an assessment of:

- plain old “harm” (Section 5),

- “serious harm to individuals or harm to their interests” (Section 4),

- “material harm” (Section 12),

- “risks of harm” (Section 8),

- “serious risk of imminent harm” (Sections 17 and 28), and

- “serious physical or psychological harm” (Section 39).

All of which is to be contrasted with the well-trodden legal analysis around the term “real risk of significant harm” which comes from privacy law.

I can assure you that lawyers will be arguing for years over the nuances of these various terms: what is the difference between “harm” and “material harm”, “risk” versus “serious risk”? and what is “serious harm” versus “material harm” versus “imminent harm”? …and what if one of these species of “harm” overlaps with a privacy issue which also triggers a “real risk of significant harm” under federal privacy laws? All of this could be clarified in future drafts of Bill C-27, which would make it easier for lawyers to advise their clients when navigating the complex legal obligations in AIDA

Stay tuned. This law has some maturing to do, and much detail is left to the regulations (which are not yet drafted).

Calgary – 16:30 MT

No commentsClick-Through Agreements

.

By Richard Stobbe

Sierra Trading Post is an Internet retailer of brand-name outdoor gear, family apparel, footwear, sporting goods. Sierra lists comparison prices on its site to show consumers that its goods are competitively priced.

Chen, the plaintiff, sued Sierra, claiming the website’s comparison prices were false, deceptive, or misleading. The internet retailer defended by asserting that the lawsuit should be dismissed: Sierra pointed out that users of its site agreed to binding arbitration in the Terms of Use. Chen countered, arguing that he had never seen the Terms of Use and so they were not binding.

In Chen v. Sierra Trading Post, Inc., 2019 WL 3564659 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 6, 2019), a US court decision, the court reviewed the issues. There was no disagreement that the choice-of-law and arbitration clauses appeared in the Terms of Use. The question, as with so many of these cases, is around the set-up of Sierra’s check-out screen. Were the Terms of Use brought to the attention of the user, so that the user consented to those terms at the point of purchase, thus evidencing a mutual agreement between the parties to be bound by those terms?

Both Canadian and US cases have been tolerant of a range of possibilities for a check-out procedure, and the placement of “click-through” terms. This applies equally to e-commerce sites, software licensing, subscription services, or online waivers. Ideally, the terms are made available for the user to read at the point of checkout, and the user or consumer has a clear opportunity to indicate assent to those terms. In some cases, the courts have accepted terms that are linked, where assent is indicated by a check-box.

While there is no specific bright-line test, the idea is to make it as easy as possible for a consumer to know (1) that there are terms and (2) that they are taking a positive step to agree to those terms.

In this case, STP claimed that Chen would have had notice of the Terms of Use via the website’s “Checkout†page where, a few lines below the “Place my order†button, a line says “By placing your order you agree to our Terms & Privacy Policyâ€. The court noted that “The Consent line contains hyperlinks to STP’s TOU and Privacy Policy.”

On balance, the court agreed to uphold the Terms of Use and compel arbitration. While this was a win for Sierra, the click-through process could easily have been much more robust. For example, rather than “Place my order”, the checkout button could have said said “By Placing my order I agree to the Terms of Use” or a separate radio button could have been placed beside the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy to indicate assent.

Internet retailers, online service providers, software vendors and anyone imposing terms through click-through contracts should ensure that their check-out process is reviewed: make it as easy as possible for a court to agree that those terms are binding.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsPrivacy Update: Will Consent be Required for Outsourcing Canadian Data?

By Richard Stobbe

Here’s a familiar picture: You are a Canadian business and you use a service provider outside of the country to process data. Let’s say this data includes personal information. This could be as simple as using Gmail for corporate email, or using Amazon Web Services (AWS) for data hosting, or hiring a UK company for CRM data processing services.Â

Until now, the Federal Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) has taken the position that data processing of this type is a “use†of personal information by the entity that collected the data for the purposes of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). Such use would require the consent of the individual for the initial collection, but would not require additional consent for the data processing by an out-of-country service provider, provided there was consent for that use at the time the information was first collected. Â

The privacy laws of some provinces contain notification requirements in certain cases, though not express consent requirements, for the use of service providers outside of Canada. For example, Alberta’s Personal Information Protection Act, Section 13.1, indicates that an organization that transfers personal information to a service provider outside Canada must notify the individual in question.Â

The OPC’s guidance, dating from 2009, took a similar approach, allowing Canadian companies to address the cross-border data processing through notification to the individual. In many cases, a company’s privacy policy might simply indicate in a general way that personal information may be processed in countries outside of Canada by foreign service providers. In the words of the commissioner in 2009: “[a]ssuming the information is being used for the purpose it was originally collected, additional consent for the transfer is not required.â€Â As long as consumers were informed of transborder transfers of personal information, and the risk that local authorities will have access to information, the organization was meeting its obligations under PIPEDA.Â

A recent consultation paper published by the OPC has signalled a potential change to that approach. If the changes are adopted by the OPC, this will represent a significant shift in data-handling practices for many Canadian companies.Â

Draft guidance from the OPC, issued April 9, 2019, indicates that recent high profile cross-border data breaches, such as the incident involving Equifax, have inspired a stricter consent-based approach. Today, the OPC issued a supplementary discussion document to explain the reasons for the proposed changes. (See: Consultation on Transborder Dataflows)

Reversing 10 years of guidance on this issue, the OPC now explains that a transfer of personal information between one organization and another should be understood as a “disclosure†according to the common understanding of that term in privacy laws.Â

If the draft guidelines are adopted by the OPC, any cross-border transfers of personal data to an outsourced service provider would be considered a “disclosureâ€, mandating a new consent, as opposed to a “use†which could be covered by the initial consent at the time of collection. Depending on the circumstances, the type of disclosure and the type of information, this could require express consent, and it’s not clear how this would apply to existing transborder data-processing agreements, or whether additional detail would be required for consent purposes, or if the specific names of the service providers would be required as part of the consent. This could significantly impact data-processing, e-commerce operations, and the consent practices of many Canadian businesses.Â

Consultations are open until June 4, 2019. Please stay tuned for further updates on this issue and if you want to seek advice on your company’s privacy obligations, please contact us.

Calgary – 16:00 MST

No commentsThe law in Canada on internet contracts: Part 2

.

By Richard Stobbe

Go-karting in Saskatchewan as an internet law case? Yes, and you’ll see why. In Quilichini v Wilson’s Greenhouse, 2017 SKQB 10 (CanLII), a go-kart participant is injured and sues the service provider. The service provider holds up the waiver as a complete defence, saying it contains a release of all claims.

In this case, the waiver is  provided to all participants through a kiosk system, where an electronic waiver is presented in a series of electronic pages on a computer screen. Participants have to click “next†to move from one page to the next; and finally click the “I agree†button on the electronic waiver before they can participate in the activity.

Variations of this happen everyday across Canada when users click “I agree”, “I accept” or some variation of a click, tap or swipe to indicate assent to a set of terms.

- Can legally binding contracts be formed in this way?

- And another question, even if it works for common-place transactions like a shopping-cart check-out, does it work for something as important as a release and waiver of the right to sue for personal injury?

The answer is a clear yes, according to the facts of this case. The judge in Quilichini had no trouble finding that the participant’s electronic agreement was just as effective as a signed hard-copy of the agreement. The participant had a full opportunity to read the waiver, and there was nothing obscure in the presentation of the waiver, or the choice whether or not to accept it. The court concluded: “there can be no question but that when the plaintiff clicked ‘I agree’, he was intending to accept and assume responsibility for any possible risk involved and knew he was agreeing to discharge or release the defendants from all claims or liabilities arising, in any way, from his participation.”

This conclusion is based in part on Canadian provincial laws such as Alberta’s Electronic Transactions Act, SA 2001, c E-5.5, (there’s an equivalent in Saskatchewan and other provinces), which generally indicate that if there is a legal requirement that a record be signed, that requirement is satisfied by an electronic signature. There are exceptions of course, such as wills or transfers of land.

In the Quilichini decision, the court didn’t look outside the Saskatchewan Electronic Information and Documents Act, 2000. But there are other authorities to support the proposition that binding contracts can be formed online in a number of ways. Decisions such as Kanitz v. Rogers Cable Inc., 2002 CanLII 49415 (ON SC), even deal with passive assent, where a user is deemed to be bound by something even absent a formal “click-through” button. Kanitz dealt with the question of whether internet service subscribers were bound by a subscription agreement, where that agreement was amended, then merely posted to the service provider’s site, rather than requiring a new signature or a fresh “click-through”. The subscribers were bound by the terms merely by continuing to use the service after the amended terms were posted.

In considering this, the Court in Kanitz said: “…we are dealing in this case with a different mode of doing business than has heretofore been generally considered by the courts. [remember… this was 2002] We are here dealing with people who wish to avail themselves of an electronic environment and the electronic services that are available through it. It does not seem unreasonable for persons who are seeking electronic access to all manner of goods, services and products, along with information, communication, entertainment and other resources, to have the legal attributes of their relationship with the very entity that is providing such electronic access, defined and communicated to them through that electronic format. I conclude, therefore, that there was adequate notice given to customers of the changes to the user agreement which then bound the plaintiffs when they continued to use the defendant’s service.” [Emphasis added]

This is not to say that ALL electronic contracts are always enforceable, or that all amendments will be enforceable even without a proper mechanism to collect the consent of users. However, it does provide a measure of confidence for Canadian internet business, that the underlying legal foundation will support the enforceability of contractual relationships when business is conducted online.

Want to review your own internet agreements and electronic contracting workflows to ensure they are binding and enforceable? Contact Richard Stobbe.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsEnforcing Rights Online: Copyright Infringement & “Norwich Orders”

.

By Richard Stobbe

When a copyright owner seeks to enforce against online copyright infringement, it often faces a problem: who is engaging in the infringing activity?  If the old adage holds true – on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog – then the corollary is that there must be a lot of canines engaged in online copyright infringement.

Of course a copyright owner can only enforce its rights against online infringement if it knows the identity of the infringer.  The Canadian solution, which is enshrined in the Copyright Act,  is the so-called “notice-and-notice” regime, which allows a copyright holder to send a notice to the ISP (internet service provider), and the ISP is obliged by the Copyright Act to send that notice to the alleged infringer, who still remains anonymous.  The notice of infringement is passed along… but the infringing content remains online.  Since the “notice-and-notice” regime is not much of an enforcement tool, the path eventually leads copyright holders to seek a court order (called a Norwich order) to disclose the identity of those alleged infringers.  (See our previous articles about Norwich Orders for background.)

In Rogers Communications Inc. v. Voltage Pictures, LLC, 2018 SCC 38, a film production company (Voltage) alleged copyright infringement by certain anonymous internet users. Allegedly, films were being shared using peer-to-peer file sharing networks. Yes, apparently peer-to-peer file sharing networks are still a thing. Voltage sued one anonymous alleged infringer and brought a motion for a Norwich order to compel the ISP (Rogers) to disclose the identity of the infringer.

Now we get to a practical problem: who pays for the disclosure of these records?

Pointing to sections 41.25 and 41.26 of the Copyright Act, Voltage argued that the disclosure order be made without anything payable to Rogers. In essence, Voltage argued that the “notice and notice†regime does two things: it creates a statutory obligation to forward the notice of claimed infringement to the anonymous infringer. The Act also prohibit ISPs from charging a fee for complying with these “notice-and-notice” obligations. In response, Rogers argued that there is a distinction between sending the notice to the anonymous infringer (for which it cannot charge a fee) and disclosing the identity of that (alleged) infringer pursuant to a Norwich order. The Act does not specify that ISPs are prohibited from charging a fee for this step.

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) agreed that there is a distinction to be made: on the one hand, an ISP has obligations under the Copyright Act to ensure the accuracy of its records for the purposes of the notice and notice regime, and on the other hand, an ISP may be obliged, under a Norwich order to actually identify a person from its records. In a nutshell, the court reasoned that ISPs must retain records under the Act, in a form and manner that permits an ISP to identify the name and address of the person to whom notice is forwarded for the “notice-and-notice” purposes. But the Act does not require that these records be kept in a form and manner which would permit a copyright owner or a court to identify that person.  The copyright owner would only be entitled to receive that kind of information from an ISP under the terms of a Norwich order. The Norwich order is a process that falls outside the ISP’s obligations under the notice and notice regime. In the end, an ISP can recover its costs of compliance with a Norwich order, but ISPs cannot be compensated for every cost that it incurs in complying with such an order:

“Recoverable costs must be reasonable and must arise from compliance with the Norwich order. Where costs should have been borne by an ISP in performing its statutory obligations under the notice and notice regime, these costs cannot be characterized as either reasonable or as arising from compliance with a Norwich order, and cannot be recovered.”

According to Rogers, there are eight steps in its process to disclose the identity of one of its subscribers in response to a Norwich order.  The SCC made reference to this eight-step process, but wasn’t in a position to decide which of these steps overlap with Rogers’ obligations under the Act (for which Rogers was not entitled to reimbursement) and the steps which are “reasonable costs of compliance” (for which Rogers was entitled to reimbursement). The question was returned to the lower court for determination.

For copyright owners, its clear that ISPs will not shoulder the entire cost of disclosing the identity of subscribers at the Norwich stage. How much of that cost will have to borne by copyright holders is, unfortunately, still not very clear.  For ISPs, this decision is a mixed bag – Rogers makes a solid argument that the costs of compliance with Norwich orders are relatively high, compared with the automated notice-and-notice procedures. While it will benefit ISPs to be able to charge some of these fees to the copyright owner, we don’t have clear guidance on the specifics.  The matter will have to be determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the ISP and their own internal procedures.

Looking for advice on Norwich orders and enforcement against online copyright infringement? Look for experienced counsel to guide you through this process.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No commentsGoogle vs. Equustek: Google Loses Another Round

By Richard Stobbe

How far can Canadian courts reach when making orders that seek to control the conduct of foreign companies outside of Canada? This controversial question is still being decided, bit by bit, in both Canadian and US courts. In our past posts we have written about a 2014 pre-trial temporary court order that required Google to de-index certain sites from Google’s worldwide search results, based on an underlying lawsuit that the plaintiff, Equustek, brought against the defendants back in 2011.  Google challenged the order requiring it to delist worldwide search results, and fought this order all the way up to the Supreme Court of Canada… where Google lost.

On July 24, 2017, approximately one month after the SCC decision, Google filed a complaint in US Federal Court, seeking an order that the injunction issued by the BC court is unlawful and unenforceable in the United States. That order was granted, first on a preliminary application on November 2, 2017 and then in a final ruling on December 14, 2017. With that US court decision in hand, Google came back to the BC court which had issued the original order, to vary the scope of that order.

On April 16, 2018, in Equustek Solutions Inc. v Jack, 2018 BCSC 610 (CanLII), the BC court again rejected Google’s requests. The BC court said that the US decision (which was in Google’s favour) did not establish that the injunction requires Google to violate American law. And without any significant change in circumstances, the court reasoned, there was no reason to change the original order. As a result, the temporary order against Google – which has been in place since 2014 – remains in place, pending outcome of the trial.

The outcome of that trial will be closely watched. As I mentioned in my earlier article, there has been very little analysis of Equustek’s IP rights by any of the different levels of court. Since this entire case involved pre-trial remedies, the merits of the underlying allegations and the strength of Equustek’s IP rights have never been tested at trial. In order for the injunction to make sense, one must assume that the IP rights were valid. Even if they are valid, it is questionable whether Equustek’s rights are worldwide in nature since there was no evidence of any worldwide patent rights or international trademark portfolio. We can only hope that the trial decision, and Google’s decision to appeal the latest BC court decision, will clarify these issues.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsGoogle vs. Equustek Saga: The Final Countdown

By Richard Stobbe

Last month we asked: The Google vs. Equustek Decision: What comes next?

Part of the answer was handed down recently by a B.C. court in Equustek Solutions Inc. v Jack, 2018 BCSC 329 (CanLII), after Google applied to vacate or vary the original order of Madam Justice Fenlon, which was granted way back in 2014. That was the order that set off a furious international debate about the reach of Canadian courts, since it required Google to de-index certain sites from Google’s worldwide search results, based on an underlying lawsuit that the plaintiff Equustek brought against the defendants (which is finally set for trial in April, 2018).

Google of course was always invited to seek a variation of that original court order. As noted by the latest judgment, that right to apply to vary has been recognized by the B.C. Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada. After Google received a favourable decision last year from a US court, the way was paved to vary the original order that has caused Google so much heartburn. The next step is that Google will seek a cancellation or limitation of the scope of that original order, so that the order applies only to search results in Canada through google.ca.

The last step, with luck, will be a hearing of the merits of the underlying IP claims; some commentators have questioned why Google was used to obtain a practical worldwide remedy when the IP rights asserted by Equustek do not appear to be global in scope. As I mentioned in my earlier article, there has been very little analysis of Equustek’s IP rights by any of the different levels of court. Since this entire case involved pre-trial remedies, the merits of the underlying allegations and the strength of Equustek’s IP rights have never been tested at trial. In order for the injunction to make sense, one must assume that the IP rights were valid. Even if they are valid, Equustek’s rights couldn’t possibly be worldwide in nature. There was no evidence of any worldwide patent rights or international trademark portfolio. So, the court somehow skipped from “the internet is borderless†to “the infringed rights are borderless†and are deserving of a worldwide remedy.

To be continued…

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Uber vs. Drivers: Canadian Court Upholds App Terms

.

By Richard Stobbe

One of Uber’s drivers, an Ontario resident named David Heller, sued Uber under a class action claim seeking $400 million in damages. What did poor Uber do to deserve this? According to the claim, drivers should be considered employees of Uber and entitled to the benefits of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act (See: Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2018 ONSC 718 (CanLII)).

As the court phrased it, while “millions of businesses and persons use Uber’s software Apps, there is a fierce debate about whether the users are customers, independent contractors, or employees.” If all of the drivers are to be treated as employees, the costs to Uber would skyrocket. Uber, of course, resisted this lawsuit, arguing that according to the app terms of service, the drivers actually enter into an agreement with Uber B.V., an entity incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands. By clicking or tapping “I agree” in the app terms of service, the drivers also accept a certain dispute resolution clause: by contract, the parties pick arbitration in Amsterdam to resolve any disputes.

Really, at this stage Uber’s defence was not to say “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers are independent contractors, not employees”. Rather, Uber argued that “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers agreed to settle disputes with us by arbitration in the Netherlands.”

So the court had to wrestle with this question:  Should the dispute resolution clause in the click-through terms be upheld? Or should the drivers be entitled to have their day in court in Canada?Â

The law in this area is very interesting and frankly, a bit muddled. This is because there are two distinct issues in this legal thicket: a forum-selection clause (the laws of the Netherlands govern any interpretation of the agreement), and a dispute resolution clause (here, arbitration is the parties’ chosen method to resolve any disputes under the agreement). For these two different issues, Canadian courts have applied different tests to determine whether such clauses should be upheld:

- In the case of forum selection clause, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) tells us that the rule from Z.I. Pompey Industries is that a forum selection clause should be enforced unless there is “strong cause†not to enforce it.  In the context of a consumer contract (as opposed to a “commercial agreement”), the SCC says there may be strong reasons to refrain from enforcing a forum selection clause (such as unequal bargaining power between the parties, the convenience and expense of litigation in another jurisdiction, public policy reasons, and the interests of justice). In the commercial context (as opposed to a consumer agreement), forum selection clauses are generally upheld.

- In the case of upholding arbitration clauses, the courts have applied a different analysis: arbitration is generally favoured as a means to settle disputes, using the “competence-competence principle”. Again, it’s an SCC decision that gives us guidance on this: unless there is clear legislative language to the contrary, or the dispute falls outside the scope of the arbitration agreement, courts must enforce arbitration agreements.

The court said this case “is not about a discretionary court jurisdiction where there is a forum selection clause to refuse to stay proceedings where a strong cause might justify refusing a stay; rather, it is about a very strong legislative direction under the Arbitration Act, 1991 or the International Commercial Arbitration Act, 2017 and numerous cases that hold that courts should only refuse a reference to arbitration if it is clear that the dispute falls outside the arbitration agreement.”

Applying the competence-competence analysis, the court (in my view) properly ruled in favour of Uber, upheld the app terms of service, and deferred this dispute to the arbitrator in the Netherlands. This class action, as a result, must hit the brakes.

The decision is reportedly under appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentCopyright Infringement on a Website: the risks of scraping and framing

By Richard Stobbe

If photos are available on the internet, then… they’re free for the taking, right?

Wait, that’s not how copyright law works? In the world of copyright, each original image theoretically has an “author” who created the image, and is the first owner of the copyright. The exception to this rule is that an image (or, indeed, any other copyright-protected work), which is created by an employee in the course of employment is owned by the employer. So, an image has an owner, even if that owner chose to post the image online. And copying that image without the permission of the owner could be an infringement of the owner’s copyright.

That seemingly simple question was the subject of a lawsuit between two rival companies who are in the business of listing online advertisements for new and used vehicles. Trader Corp. had a head start in the Canadian marketplace with its autotrader.ca website. Trader had the practice of training its employees and contractors to take vehicle photos in a certain way, with certain staging and lighting. A U.S. competitor, CarGurus, entered the market in 2015. It was CarGurus practice to obtain its vehicle images by “indexing†or “scraping†Dealers’ websites. Essentially, the CarGurus software would “crawl†an online image to identify data of interest, and then extract the data for use on the CarGurus site.

As part of its “indexing†or “scrapingâ€, the CarGurus site apparently included some photos that were owned by Trader. Although some back-and-forth between the parties resulted in the takedown of a large number of images from the CarGurus site, the dispute boiled over into litigation in late 2015 – the lawsuit by Trader alleged copyright infringement in relation to thousands of photos over which Trader claimed ownership.

Some interesting points arise from the decision in Trader v. CarGurus, 2017 ONSC 1841 (CanLII):

Trader was only able to establish ownership in 152,532 photos. There were thousands of photos for which Trader could not show convincing evidence of ownership. This speaks to the inherent difficulty in establishing a solid evidentiary record of ownership of individual images across a complex business operation.

CarGurus raised a number of noteworthy defences:

- First, CarGurus argued that in the case of some of the photos there was no actual “copying” or “reproduction” of the original image file. Rather, CarGurus argued that it merely framed the image files. Put another way, “although the images from Dealers’ websites appeared to be part of CarGurus’ website, they were not physically present on CarGurus’ server, but located on servers hosting the Dealers’ websites.”

The court was not convinced by the novel argument. “In my view” the court declared, “when CarGurus displayed the photo on its website, it was ‘making it available’ to the public by telecommunication (in a way that allowed a member of the public to have access to it from a place and at a time individually chosen by that member), regardless of whether the photo was actually stored on CarGurus’ server or on a third party’s server.”

The court decided that by making the images available to the public in through its framing technique, CarGurus infringed Trader’s copyright.

This tells us that copyright infringement can occur even where the infringer is not storing or hosting the copyright-protected work on its own server. - Second, CarGurus attempted to mount a “fair dealing” defense. It is not an infringement if the copying is for the purpose of “research or private study.” The court also rejected this argument, saying that even if a consumer was engaged in “research” when viewing the images in the course of car shopping, it would be too much of a stretch to accept that CarGurus was engaged in research. Theirs was clearly a commercial purpose.

- Lastly, the lawyers for CarGuru argued that, even if infringement did occur, CarGurus should be shielded from any damages award by virtue of section 41.27(1) of the Copyright Act. This provision was originally designed as a “safe harbour” for search engines and other network intermediaries who might inadvertently cache or reproduce copyright-protected works in the course of providing services, provided the search engine or intermediary met the definition of an “information location toolâ€. Although CarGurus does assist users with search functions (after all, it searches and finds vehicle listings), the court batted away this argument, pointing out that CarGurus cannot be considered an intermediary in the same way a search engine is. This particular subsection has never been the subject of judicial interpretation until now.

Having dismissed these defences, the Court assessed damages for copyright infringement at $2.00 per photo, for a total statutory damages award in the amount of $305,064.

CALGARY – 07:00 MT

No commentsAnother Canadian Decision Reaches Outside Canada

By Richard Stobbe

This fascinating Ontario case deals with an Alberta-based individual who complained of certain material that was re-published on the website Globe24h.com based in Romania. The server that hosted the website was located in Romania. The material in question was essentially a re-publication of certain publicly available Canadian court and tribunal decisions.

The Alberta individual complained that this conduct – the re-publication of a Canadian tribunal decision on a foreign server – was a breach of his privacy rights since he was named personally in this tribunal decision.

So, let’s get this straight, this is a privacy-based complaint relating to republication in public of a publicly available decision?

Yes, you heard that right. This Romanian site scraped decisions from Canadian court and tribunal websites (information that was already online) and made this content searchable on the internet (making it …available online).

This is an interesting decision, and we’ll just review two elements:

The first issue was whether Canadian privacy laws (such as PIPEDA ) have extraterritorial application to Globe24h.com as a foreign-based organization.  On this point, the Ontario court, citing a range of past decisions (including the Google v. Equustek decision which is currently being appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada) said:

“In this case, the location of the website operator and host server is Romania. However, when an organization’s activities take place exclusively through a website, the physical location of the website operator or host server is not determinative because telecommunications occur “both here and thereâ€: Libman v The Queen, 1985 CanLII 51 (SCC), [1985] 2 SCR 178 at p 208 [Emphasis added]

Secondly, the Ontario court reviewed whether the Romanian business was engaged in “commercial activities” (since that is an element of PIPEDA) . The court noted the Romanian site  “was seeking payment for the removal of the personal information from the website. The fees solicited for doingdoing so varied widely. Moreover, if payment was made with respect to removal of one version of the decision, additional payments could be demanded for removal of other versions of the same information. This included, for example, the translation of the same decision in a Federal Court proceeding or earlier rulings in the same case.”

The Romanian site made a business out of removing data from this content, but the court’s conclusion that “The evidence leads to the conclusion that the respondent was running a profit-making scheme to exploit the online publication of Canadian court and tribunal decisions containing personal information.” [Emphasis added] – in a general sense, that statement could just as easily apply to Google or any of the commercial legal databases which are marketed to lawyers.

The court concluded that it could take jurisdiction over the Romanian website, and ordered the foreign party to take-down the offending content.

This decision represent another reach by a Canadian court to takedown content that has implications outside the borders of Canada. Â From the context, it is likely that this decision is going to stand, since the respondent did not contest this lawsuit. The issue of extra-terrtorial reach of Canadian courts in the internet context is going to be overtaken by the pending Supreme Court decision in Equustek. Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Is there copyright in a screenshot?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Ever wanted to remove something after it had been swallowed up in the gaping maw of the internet? Then you will relate to this story about an individual’s struggle to have certain content deleted from the self-appointed memory banks of the web.

The Federal Court recently rendered a procedural decision in the case of Davydiuk v. Internet Archive Canada and Internet Archive 2016 FC 1313 (for background, visit the Wayback Machine… or see our original post Copyright Implications of a “Right to be Forgottenâ€? Or How to Take-Down the Internet Archive).

For those who forget the details, this case relates to a long-running plan by Mr. Davydiuk to remove certain adult video content in which he appeared about a dozen years ago. He secured the copyright in the videos and all related material including images and photographs, and went about using copyright to remove the online reproductions of the content. In 2009, he discovered that Internet Archive, a defendant in these proceedings, was hosting some of this video material as part of its web archive collection.  It is Mr. Davydiuk’s apparent goal to remove all of the content from the Internet Archive – not only the video but also associated images, photos, and screenshots taken from the video.

The merits of the case are still to be decided, but the Federal Court has decided a procedural matter which touches upon an interesting copyright question:

When a screenshot is taken from a video, is there sufficient originality for copyright to extend to that screenshot? Or is it a “purely mechanical exercise not capable of copyright protection”?

This case is really about the use of copyright in aid of personal information and privacy goals. The Internet Archive argued that it shouldn’t be obliged to remove material for which there is no copyright. Remember, for copyright to attach to a work, it must be “original”. The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has made it clear that:

For a work to be “original†within the meaning of the Copyright Act, it must be more than a mere copy of another work. At the same time, it need not be creative, in the sense of being novel or unique. What is required to attract copyright protection in the expression of an idea is an exercise of skill and judgment. By skill, I mean the use of one’s knowledge, developed aptitude or practised ability in producing the work. By judgment, I mean the use of one’s capacity for discernment or ability to form an opinion or evaluation by comparing different possible options in producing the work. This exercise of skill and judgment will necessarily involve intellectual effort. The exercise of skill and judgment required to produce the work must not be so trivial that it could be characterized as a purely mechanical exercise. For example, any skill and judgment that might be involved in simply changing the font of a work to produce “another†work would be too trivial to merit copyright protection as an “original†work. [Emphasis added]

From this, we know that changing font (without more) is NOT sufficient to qualify for the purposes of originality. Making a “mere copy” of another work is also not considered original. For example, an exact replica photo of a photo is not original, and the replica photo will not enjoy copyright protection.  So where does a screenshot fall?

The Internet Archive argued that the video screenshots were not like original photographs, but more like a photo of a photo – a mere unoriginal copy of a work requiring a trivial effort.

On the other side, the plaintiff argued that someone had to make a decision in selecting which screenshots to extract from the original video, and this represented an exercise of sufficient “skill and judgment”. The SCC did not say that the bar for “skill and judgment” is very high – it just has to be higher than a purely mechanical exercise.

At this stage in the lawsuit, the court merely found that there was enough evidence to show that this is a genuine issue. In other words, the issue is a live one, and it has to be assessed with the benefit of all the evidence. So far, the issue of copyright in a screenshot is still undetermined, but we can see from the court’s reasoning that if there is evidence of the exercise of “skill and judgment” involved in the decision-making process as to which particular screenshots to take, then these screenshots will be capable of supporting copyright protection.

Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsGoogle v. The Court: Free Speech and IP Rights (Part 2)

By Richard Stobbe

Last week, hearings concluded in the important case of Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., et al.  The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) will render its judgment in writing, and the current expectation is that it will clarify the limits of extraterritoriality, and the unique issues of protected expression in the context of IP rights and search engines.

In Part 1, I admonished Google, saying “you’re not a natural person and you don’t enjoy Charter rights.” Some commentators have pointed out that this is too broad, and that’s a fair comment.  Indeed, it’s worth clarifying that corporate entities can benefit from certain Charter rights, and can challenge a law on the basis of unconstitutionality. The Court has also held that freedom of expression under s. 2(b) can include commercial expression, and that government action to unreasonably restrict that expression can properly be the subject of a Charter challenge.

The counter-argument about delimiting corporate enjoyment of Charter rights is grounded in a line of cases stretching back to the SCC’s 1989 decision in Irwin Toy where the court was clear that the term “everyone” in s. 7 of the Charter, read in light of the rest of that section, excludes “corporations and other artificial entities incapable of enjoying life, liberty or security of the person, and includes only human beings”.

Thus, in Irwin Toy and Dywidag Systems v. Zutphen Brothers (see also: Mancuso v. Canada (National Health and Welfare), 2015 FCA 227 (CanLII)), the SCC has consistently held that corporations do not have the capacity to enjoy certain Charter-protected interests – particularly life, liberty and security of the person – since these are attributes of human beings and not artificial persons such as corporate entities.

It is also worth noting that the Charter is understood to place restrictions on government, but does not provide a right of a corporation to enforce Charter rights as against another corporation. Put another way, one corporation cannot raise a claim that another corporation has violated its Charter rights. While there can be no doubt that a corporation cannot avail itself of the protection offered by section 7 of the Charter, a corporate entity can avail itself of Charter protections related to unreasonable limits on commercial expression, where such limits have been placed on the corporate entity by the government – for example, by a law or regulation enacted by provincial or federal governments.

There is a good argument that the limited Charter rights that are afforded to corporate entities should not extend to permit a corporation to complain of a Charter violation where its “commercial expression” is restricted at the behest of another corporation in the context of an intellectual property infringement dispute.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentGoogle v. The Court: Free Speech and IP Rights (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., et al., the long-running case involving a court’s ability to restrict online search results, and Google’s obligations to restrict search results has finally reached the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). Hearings are proceeding this week, and the list of intervenors jostling for position at the podium is like a who’s-who of free speech advocates and media lobby groups. Here is a list of many of the intervenors who will have representatives in attendance, some of whom have their 10 minutes of fame to speak at the hearing:

- The Attorney General of Canada,

- Attorney General of Ontario,

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association,

- OpenMedia Engagement Network,

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press,

- American Society of News Editors,

- Association of Alternative Newsmedia,

- Center for Investigative Reporting,

- Dow Jones & Company, Inc.,

- First Amendment Coalition,

- First Look Media Works Inc.,

- New England First Amendment Coalition,

- Newspaper Association of America,

- AOL Inc.,

- California Newspaper Publishers Association,

- Associated Press,

- Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University,

- Online News Association and the Society of Professional Journalists (joint as the Media Coalition),

- Human Rights Watch,

- ARTICLE 19,

- Open Net (Korea),

- Software Freedom Law Centre and the Center for Technology and Society (joint),

- Wikimedia Foundation,

- British Columbia Civil Liberties Association,

- Electronic Frontier Foundation,

- International Federation of the Phonographic Industry,

- Music Canada,

- Canadian Publishers’ Council,

- Association of Canadian Publishers,

- International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers,

- International Confederation of Music Publishers and the Worldwide Independent Network (joint) and

- International Federation of Film Producers Associations.

The line-up at Starbucks must have been killer.

The case has generated a lot of interest, including this recent article (Should Canadian Courts Have the Power to Censor Search Results?) which speaks to the underlying unease that many have with the precedent that could be set and its wider implications for free speech.

You may recall that this case is originally about IP rights, not free speech rights. Equustek sued Datalink Technologies for infringement of the IP rights of Equustek. The original lawsuit was based on trademark infringement and misappropriation of trade secrets. Equustek successfully obtained injunctions prohibiting this infringement. It was Equustek’s efforts at stopping the ongoing online infringement, however, that first led to the injunction prohibiting Google from serving up search results which directed customers to the infringing websites.

It is common for an intellectual property infringer (as the defendant Datalink was in this case) to be ordered to remove offending material from a website. Even an intermediary such as YouTube or another social media platform, can be compelled to remove infringing material – infringing trademarks, counterfeit products, even defamatory materials. That is not unusual, nor should it automatically touch off a debate about free speech rights and government censorship.

This is because the Charter-protected rights of freedom of speech are much different from the enforcement of IP rights.

The Court of Appeal did turn its attention to free speech issues, noting that “courts should be very cautious in making orders that might place limits on expression in another country. Where there is a realistic possibility that an order with extraterritorial effect may offend another state’s core values, the order should not be made.  In the case before us, there is no realistic assertion that the judge’s order will offend the sensibilities of any other nation. It has not been suggested that the order prohibiting the defendants from advertising wares that violate the intellectual property rights of the plaintiffs offends the core values of any nation. The order made against Google is a very limited ancillary order designed to ensure that the plaintiffs’ core rights are respected.”

Thus, the fear cannot be that this order against Google impinges on free-speech rights; rather, there is a broader fear about the ability of any court to order a search engine to restrict certain search results in a way that might be used to restrict free speech rights in other situations.  In Canada, the Charter guarantees that everyone has the right to: “freedom of …expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication…” It is important to remember that in Canada a corporation is not entitled to guarantees found in Section 7 of the Charter. (See: Irwin Toy Ltd. v. Quebec (Attorney General), 1989 CanLII 87 (SCC), [1989] 1 S.C.R. 927)

So, while there have been complaints that Charter rights have been given short shrift in the lower court decisions dealing with the injunction against Google, it’s worth remembering that Google cannot avail itself of these protections. Sorry Google, but you’re not a natural person and you don’t enjoy Charter rights. [See Part 2 for more discussion on a corporation’s entitlement to Charter protections.]

Although free speech will be hotly debated at the courthouse, the Google case is, perhaps, not the appropriate case to test the limits of free speech. This is a case about IP rights enforcement, not government censorship.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentUse of a Trademark on Software in Canada

.

By Richard Stobbe

Xylem Water Solutions is the owner of the registered Canadian trademark AQUAVIEW in association with software for water treatment plants and pump stations. Â Xylem received a Section 45 notice from a trademark lawyer, probably on behalf of an anonymous competitor of Xylem, or an anonymous party who wanted to claim the mark AQUAVIEW for themselves. This is a common tactic to challenge, and perhaps knock-out, a competitor’s mark.

A Section 45 notice under the Trade-marks Act requires the owner of a registered trademark to prove that the mark has been used in Canada during the three-year period immediately before the notice date. As readers of ipblog.ca will know, the term “use” has a special meaning in trademark law. In this case, Xylem was put to the task of showing “use” of the mark AQUAVIEW in association with software.

How does a software vendor show “use” of a trademark on software in Canada?

The Act tells us that “A trade-mark is deemed to be used in association with goods if, at the time of the transfer of the property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade, it is marked on the goods themselves or on the packages in which they are distributed…” (Section 4)

The general rule is that a trademark should be displayed at the point of sale (See: our earlier post on Scott Paper v. Georgia Pacific). In that case, involving a toilet paper trademark, Georgia-Pacific’s mark had not developed any reputation since it was not visible until after the packaging was opened. As we noted in our earlier post, if a mark is not visible at the point of purchase, it can’t function as a trade-mark, regardless of how many times consumers saw the mark after they opened the packaging to use the product.

The decision in Ashenmil v Xylem Water Solutions AB, 2016 TMOB 155 (CanLII),  tackles this problem as it relates to software sales. In some ways, Xylem faced a similar problem to the one which faced Georgia-Pacific. The evidence showed that the AQUAVIEW mark was displayed on website screenshots, technical specifications, and screenshots from the software.

The decision frames the problem this way: “…even if the Mark did appear onscreen during operation of the software, it would have been seen by the user only after the purchaser had acquired the software. Â … seeing a mark displayed, when the software is operating without proof of the mark having been used at the time of the transfer of possession of the ware, is not use of the mark” as required by the Act.

The decision ultimately accepted this evidence of use and upheld the registration of the AQUAVIEW mark. It’s worth noting the following take-aways from the decision:

- The display of a mark within the actual software would be viewed by customers only after transfer of the software. Â This kind of display might constitute use of the mark in cases where a customer renews its license, but is unlikely to suffice as evidence of use for new customers.

- In this case, the software was “complicated” software for water treatment plants. The owner sold only four licenses in Canada within a three-year period.  In light of this, it was reasonable to infer that purchasers would take their time in making a decision and would have reviewed the technical documentation prior to purchase.  Thus, the display of the mark on technical documentation was accepted as “use” prior to the purchase. This would not be the case for, say, a 99¢ mobile app or off-the-shelf consumer software where technical documentation is unlikely to be reviewed prior to purchase.

- Website screenshots and digital marketing brochures which clearly display the mark can bolster the evidence of use. Again, depending on the software, purchasers can be expected to review such materials prior to purchase.

- Software companies are well advised to ensure that their marks are clearly displayed on materials that the purchaser sees prior to purchase, which will differ depending on the type of software. The display of a mark on software screenshots is not discouraged; but it should not be the only evidence of use. If software is downloadable, then the mark should be clearly displayed to the purchaser at the point of checkout.

- The cases have shown some flexibility to determine each case on its facts, but don’t rely on the mercy of the court: software vendors should ensure that they have strong evidence of actual use of the mark prior to purchase. Clear evidence may even prevent a section 45 challenge in the first place.

To discuss protection for your software and trademarks, Â contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAndroid vs. Java: Copyright Update

By Richard Stobbe

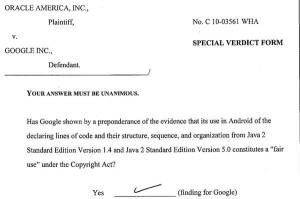

In a sprawling,  billion-dollar lawsuit that started in 2010, a jury yesterday returned a verdict in favour of Google, delivering a blow to Oracle.  (For those who have lost the thread of this story, see : API Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round).

The essence of Oracle America Inc. v. Google Inc. is a claim by Oracle that Google’s Android operating system copied a number of APIs from Oracle’s Java code, and this copying constituted copyright infringement. Infringement, Oracle argued, that should give rise to damages based on Google’s use of Android. Now think for a minute of the profits that Google might attribute to its use of Android, which has dominated mobile operating system since its introduction in 2007. Oracle claimed damages of almost $10 billion.

In prior decisions, the US Federal Court decided that Google’s copying did infringe Oracle’s copyright. The central issue in this phase was whether Google could sustain a ‘fair use’ defense to that infringement. Yesterday, the jury sided with Google, deciding that Google’s use of the copied code constituted ‘fair use’, effectively quashing Oracle’s damages claim.

Oracle reportedly vowed to appeal.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsLiability of Cloud-Based Service Provider For Data Breach

By Richard Stobbe

Silverpop Systems provides digital marketing services through a cloud-based tool called ‘Engage’. Leading Market Technologies, Inc. (“LMT”) engaged Silverpop through a service agreement and during the course of that agreement LMT uploaded digital advertising content and recipient e-mail addresses to the Engage system. A trove of nearly half a million e-mail addresses, provided by LMT, was stored on the Engage online system. In November 2010, Silverpop’s system was hacked, putting LMT’s email list at risk. Silverpop notified LMT of the data breach. After LMT refused to pay for further service, Silverpop suspended the agreement.

Litigation commenced in 2012, with LMT claiming damages for breach of contract and negligence based on Silverpop’s failure to keep the email list secure. Should the service provider be liable? Silverpop argued that it was engaged to provide access to its online system, not specifically to keep data secure. Thus there was no breach of its obligations under the agreement. And anyway, if LMT suffered any damages, they were indirect or consequential and consequential such damages were excluded under the terms of the agreement. LMT countered that, in fact, the agreement quite clearly contained a confidentiality clause, and that the damages suffered by LMT were direct damages, not indirect consequential damages.

The US Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in Silverpop Systems Inc. v. Leading Market Technologies Inc. sided with Silverpop:

- “Here, the parties’ agreement was not one for the safeguarding of the LMT List. Rather, the parties contracted for the providing of e-mail marketing services. While it was necessary for LMT to provide a list of intended recipients (represented as e-mail addresses on the LMT List) to ensure that the service Silverpop provided (targeted e-mail marketing) was carried out, the safe storage of the list was not the purpose of the agreement between the parties.” (Emphasis added)

The court was careful to review both the limit of liability clause (which provided an overall cap on liability to 12 months fees), and the exclusion clause (which barred recovery for indirect or consequential damages). The overall limit of liability had an exception: the cap did not apply to a breach of the confidentiality obligation. However, this exception did not impact the scope of the limit on indirect or consequential damages. Since the court decided that the claimed breach did not result from a failure of performance, and the consequential damages clause applied to LMT’s alleged loss. As a result, LMT’s claims were dismissed.

Lessons for business?

- Those limitation of liability and exclusion clauses are often considered “boilerplate”. But they really do make a difference in the event of a claim. Ensure you have experienced counsel providing advice when negotiating these clauses, from either the customer or service provider perspective.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsClickwrap Agreement From a Paper Contract?

By Richard Stobbe

Can a binding contract be formed merely with a link to another set of terms? (For background on this topic, check out our earlier post What, exactly, is a browsewrap? which reviews browsewraps, clickwraps, clickthroughs, terms of use, terms of service and EULAs).

The answer is clearly… it depends. Consider the American case of Holdbrook Pediatric Dental, LLC, v. Pro Computer Service, LLC (PCS), a New Jersey decision which considered the enforceability of a set of terms which were linked from a paper hard-copy version of the contract. In this case, PCS sent a contract to its customer electronically. The customer printed out the paper version and signed it in hard copy. A hyperlink appeared near the signature line, pointing to a separate set of Terms and Conditions in HTML code. Of course on the paper copy these terms cannot be hyperlinked.

PCS asserted that these separate terms were incorporated into the signed paper contract, since they function as a clickable hyperlink in the electronic version.  The court disagreed: “In order for there to be a proper and enforceable incorporation by reference of a separate document . . . the party to be bound by the terms must have had ‘knowledge of and assented to the incorporated terms.’”  Here, there was no independent assent to the additional Terms and Conditions, and the mixed media nature of the contracting process worked against PCS. In addition to the fact that the separate terms were not easily accessible by the customer, the text was not clear. It merely said “Download Terms and Conditions”, without providing reasonable notice to the customer that assent to the main contract included assent to these additional terms. The additional terms were not binding on the customer.

Lessons for business? Get legal advice!

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCASL Enforcement (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As reviewed in Part 1, since July 1, 2014, Canada’s Anti-Spam Law (or CASL) has been in effect, and the software-related provisions have been in force since January 15, 2015.

In January, 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) executed a search warrant at business locations in Ontario in the course of an ongoing investigation relating to the installation of malicious software (malware) (See: CRTC executes warrant in malicious malware investigation). The allegations also involve alteration of transmission data (such as an email’s address, date, time, origin) contrary to CASL. This represents one of the first enforcement actions under the computer-program provisions of CASL.

The first publicized case came in December, 2015, when the CRTC announced that it took down a “command-and-control server” located in Toronto as part of a coordinated international effort, working together with Federal Bureau of Investigation, Europol, Interpol, and the RCMP. This is perhaps the closest the CRTC gets to international criminal drama. (See: CRTC serves its first-ever warrant under CASL in botnet takedown).

Given the proliferation of malware, two actions in the span of a year cannot be described as aggressive enforcement, but it is very likely that this represents the visible tip of the iceberg of ongoing investigations.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentOnline Infringement and Norwich Orders: an update

.

By Richard Stobbe

This is a case that became something of a lightning rod in the storm of subscriber privacy rights vs. copyright. As we wrote in our earlier post, a copyright owner can only enforce its rights against online infringement if it knows the identity of the infringer. It can seek a court order (called a Norwich order) to disclose the identity of those alleged infringers. Canadian law is clear that “A court order is required in every case as a condition precedent to the release of subscriber information.â€

Such an order was used by Voltage Pictures to obtain the names and addresses of some 2,000 subscribers of an ISP known TekSavvy Solutions Inc. TekSavvy sought reimbursement of its costs for complying with the order: TekSavvy claimed recovery of a total of $346,480.68. Voltage offered to pay $884.00. The lower court concluded that Voltage should pay $21,557.50 to cover TekSavvy’s legal costs, administrative costs, and disbursements of abiding with the Order.

TekSavvy appealed that order.

In Voltage Pictures LLC v. John Doe, 2015 FC 1364 (CanLII), the court awarded TekSavvy an additional amount of $11,822.50. A win? Not really, considering how much they claimed, and what it would have cost to run the appeal.

The court also wagged a finger at TekSavvy. Since TekSavvy was only obliged to deliver the subscriber info after payment of its costs, the payment issue resulted in a significant delay in the supply of the subscriber names. The court complained that “…Voltage has not been able to obtain the information that it was lawfully entitled to for more than two years after Prothonotary Aalto’s Order. The failure to provide this information, on all accounts, appears to be due to TekSavvy’s unwarranted and excessive cost claims in the amount now of $350,000…”

It went on to note that “…the background circumstantial results do not sit well with the Court. They confirm that the policy in these types of motions should normally be to facilitate the plaintiff’s legitimate efforts to obtain the information from ISPs on the prima facie illegal activities of its subscribers. In my view, courts should be careful not to allow the ISP’s intervention to unduly interfere in the copyright holder’s efforts to pursue the subscribers, except where a good case is made out to do so. While it may be a practice to require prepayment of the ISP’s costs of the motion, the court must not let this issue delay unnecessarily the execution of the order to the extent possible. Reasonable security for costs may be preferable in some cases.” [Emphasis added]

As with the earlier decision, this case serves as guidance to copyright holders who are seeking the information of anonymous infringers, and to ISPs who must balance the privacy rights of subscribers.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentLimitations of Liability: Do they work in the Alberta Oilpatch?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s consider that contract you’re about to sign. Does it contain a limitation of liability? And if so, are those even enforceable? It’s been several years since we last wrote about limitations of liability and exclusion clauses (See: Limitations of Liability: Do they work?) and it’s time for another look.

A limitation of liability seeks to reduce or cap one party’s liability to a certain dollar amount – usually a nominal amount. An exclusion clause is a bit different – the exclusion clause seeks to preclude any contractual claim whatsoever.

To understand the current state of the law, we have to look at the decision in Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. British Columbia (Transportation and Highways), 2010 SCC 4 (CanLII), 315 D.L.R. (4th) 385, where the Supreme Court of Canada laid down a three-part framework. This test requires the court to determine:

(a) whether, as a matter of interpretation, the exclusion clause applies to the circumstances established in the evidence;

(b) if the exclusion clause applies, whether the clause was unconscionable and therefore invalid, at the time the contract was made; and

(c) if the clause is held to be valid under (b), whether the Court should nevertheless refuse to enforce the exclusion clause, because of an “overriding public policy, proof of which lies on the other party seeking to avoid enforcement of the clause, that outweighs the very strong public interest in the enforcement of contractsâ€.

We can illustrate this if we apply these concepts to a recent Alberta case. In this case, the court considered a limitation of liability in the context of a standard form industry contract, the terms of which were negotiated between the Canadian Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Anyone doing business in the Alberta oilpatch will have seen one of these agreements, or something similar.

The court describes this agreement as a bilateral no-fault contract, where one party takes responsibility for damage or loss of its own equipment, regardless of how that damage or loss was caused. Precision Drilling Canada Limited Partnership v Yangarra Resources Ltd., 2015 ABQB 433 (CanLII) dealt with a situation where one of Precision’s employees caused damage to Yangarra’s well. In the end Yangarra lost $300,000 worth of equipment down the well, which was abandoned. Add the cost of fishing operations to retrieve the lost equipment (about $720,000), and add the cost of drilling a relief well (about $2.5 million). All of this could be traced to the conduct of one of Precision’s employees – ouch.

Despite all of this, the court decided that the bilateral risk allocation (exclusion of liability) clauses in the contract between Yangarra and Precision applied to allocate these costs to Yangarra, regardless of who caused the losses. The court decided that enforcing this limitation of liability clause was neither unconscionable nor contrary to public policy. The clause was upheld, and Precision escaped liability.

Calgary – 07:00

No comments