Oh Canada! … in Trademarks

By Richard Stobbe

In honour of Canada Day tomorrow (for our American readers, that’s the equivalent of Independence Day, with the beer, hotdogs and fireworks, but without the summer blockbuster movie to go along with it), here is our venerable national anthem… in trademarks:

OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey), our HOME AND NATIVE LAND (registered for key chains, mugs, coasters and place mats, but expunged for failure to renew in 2012), TRUE PATRIOT LOVE (registered for accepting and administering charitable contributions to support the Canadian Military and their families) in all our sons command (until the lyrics are amended through a private members bill)! WITH GLOWING HEARTS (abandoned) we see thee rise, the TRUE NORTH (registered for footwear namely shoes, boots, slippers and sandals) STRONG AND FREE (registered for T-shirts, sweaters, and hats)! From far and wide, OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey),  WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee! God keep OUR LAND (registered for fresh fruit), GLORIOUS AND FREE (registered for athletic wear, beachwear, casual wear, golf wear, gym wear, outdoor winter clothing and fridge magnets)! OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey) we stand ON GUARD FOR THEE (registered for travel health insurance services, but abandoned in 1996)! WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee!

Happy Canada Day!

Calgary – 12:00 MST

No comments“Wow Moments” and Industrial Design Infringement

By Richard Stobbe

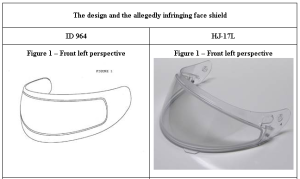

An inventor had a “wow” moment when he came across a design improvement for cold-weather visors – something suitable for the snowmobile helmet market. The helmet maker brought the improved helmet to market and also pursued both patent and industrial design protection. The patent application was ultimately abandoned, but the industrial design registration was issued in 2010 for the “Helmet Face Shield†design, which purports to protect the visor portion of a snowmobile helmet.

AFX Licensing, the owner of the invention, sued a competitor for infringement of the registered industrial design. AFX sought an injunction and damages for infringement under the Industrial Design Act.  The competitor – HJC America – countered with an application to expunge the registration on the basis of invalidity. HJC argued that the design was invalid due to a lack of originality and due to functionality.

Can a snowmobile visor be protected using IP rights?

A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration.

In AFX Licensing Corporation v. HJC America, Inc., 2016 FC 435 (CanLII),  the court decided that AFX’s industrial design registration was valid but was not infringed by the HJC product because the court saw “substantial differences” between the two designs. In summarizing, the court noted the following:

“First, the protection offered by the industrial design regime is different from that of the patent regime…Â the patent regime protects functionality and the design regime protects the aesthetic features of any given product.” (Emphasis added)

The industrial design registration obtained by AFXÂ does “not confer on AFX a monopoly over double-walled anti-fogging face shields in Canada. Rather, it provides a measure of protection for any shield that is substantially similar to that depicted in the ID 964 illustrations, and it cannot be said that the HJ-17L meets that threshold.”

The infringement claim and the expungement counter-claim were both dismissed.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsBREXIT and IP Rights for Canadian Business

By Richard Stobbe

Yesterday UK voters elected to approve a withdrawal from the EU.  What does this mean for Canadian business owners who have intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK?

The first message for Canadian IP rights holders is (in true British style) remain calm and keep a stiff upper lip. All of this is going to take a while to sort out and rights holders will have advance notice of the various means to protect their rights in an orderly fashion. The British are not known for rash actions — ok, other than the Brexit vote.

Rights granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), will be impacted, although the extent of the impact is still to be negotiated and settled. The UK’s membership in WIPO (the World International Property Organisation) is independent of EU membership and so will not be affected by this process. Similarly, the UK’s participation in the European Patent Convention is not dependent on EU membership.

Current speculation is that EU Trade Marks will continue to be recognized as valid in the EU, although such rights will not be recognized in the UK. This may require Canadian rights holders to submit new applications for those marks in the UK, or there may be a negotiated conversion of those EUIPO rights into national UK rights, permitting these registered marks to be recognized both in the EU and the UK.

Copyright law should not be dramatically impacted, since many of the rights of Canadian copyright holders would benefit from international copyright conventions that predate the EU era. However, UK copyright law was undergoing a process to become aligned with EU laws. For example, recent amendments to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were enacted in 2014 to implement EU Directive 2001/29, and the fate of these statutory amendments remains unclear at the moment.

Again, this won’t happen overnight.  Many bureaucrats must debate many regulations before the way forward becomes clear. That’s not much of a rallying cry but it is the reality for an unprecedented event such as this. The good news? If you are a EU IP rights negotiator, you will have steady employment for the next few years.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Series: Words in a foreign language

By Richard Stobbe

A word that clearly describes a particular product or service cannot function as a trademark for that product or service. The Trademarks Act phrases this idea in a more formal way: section 12(1)(b) says that a trade-mark is registrable if it is not … “whether depicted, written or sounded, either clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive in the English or French language of the character or quality of the wares or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used or of the conditions of or the persons employed in their production or of their place of origin”. (Emphasis added)

The case of  Primalda Industries Corp v Morinda, Inc., 2004 CanLII 71759 (CA TMOB), reviewed an application for the trade-mark TAHITIAN NONI Design, for the following wares: “skin care preparations; namely, cleansers, lotions, gels, moisturizing creams” and similar products. The term TAHITIAN NONI refers to the morinda citrifolia tree, which is commonly known as ‘NONI’ in the Polynesian language.  The application was opposed based on a challenge that the mark offended section 12(1)(b) since it was “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive” of the products, by virtue of the fact that the name is a clear description of ingredients in the skin care products, which are derived from the fruit of the ‘Tahitian NONI’ tree.

This might be like trying to register the word CANADIAN MAPLE in association with skin care products derived from, say, the syrup from the maple tree.

However, after reviewing the Act, the court rejected this ground of opposition. Why?

“It is self-evident from the legislation,” the Court said, “that words that might be descriptive in a language other than French or English are not subject to paragraph 12(1)(b). As the opponent alleges in its statement of opposition that ‘NONI’ is a Polynesian word and there is no evidence that it is an English or French word, I conclude that TAHITIAN NONI Design cannot be unregistrable pursuant to paragraph 12(1)(b).”

In short, a clearly descriptive word can be registrable in Canada as long as it is not descriptive in the English of French language.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright and the Creative Commons License

By Richard Stobbe

There are dozens of online photo-sharing platforms. When using such photo-sharing venues, photographers should take care not to make the same mistake as Art Drauglis, who posted a photo to his online account through the photo-sharing site Flickr, and then discovered that it had been published on the cover of someone else’s book. Mr. Drauglis made his photo available through a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which permitted reproduction of his photo, even for commercial purposes.

You might be surprised to find out how much online content is licensed through the “Creative Commons†licensing regime. According to recent estimates, adoption of Creative Commons (CC) has expanded from 140 million licensed works in 2006, to over 1 billion today, including hundreds of millions of images and videos.

In the decision in Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group LLC (U.S. District Court D.C., cv-14-1043, Aug. 18, 2015), the federal court acknowledged that, under the terms of the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, the photo was licensed for commercial use, so long as proper attribution was given according to the technical requirements in the license. The court found that Kappa Map Group complied with the attribution requirements by listing the essential information on the back cover. The publisher’s use of the photo did not exceed the scope of the CC license; the copyright claim was dismissed.

There are several flavours of CC license:

- The Attribution License (known as CC BY)

- The Attribution-ShareAlike License (CC BY-SA)

- The Attribution-NoDerivs License (CC BY-ND)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial License (CC BY-NC)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (CC BY-NC-ND)

- Lastly, a so-called Public Domain (CC0) designation permits the owner of a work to make it available with “No Rights Reservedâ€, essentially waiving all copyright claims.

Looks confusing? Even within these categories, there are variations and iterations. For example, there is a version 1.0, all the way up to version 4.0 of each license. The licenses are also translated into multiple languages.

Remember: “available on the internet†is not the same as “free for the takingâ€. Get advice on the use of content which is made available under any Creative Commons license.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments