Copyright Fight: Hollywood versus a Film School Project

By Richard Stobbe

In 2015 Pixar, Disney’s animation company, released INSIDE OUT, a feature-length animated film featuring a character whose emotions of Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust take the form of personified characters.  Did Pixar’s 2015 production infringe the copyright in the film school project from fifteen years earlier? That’s what Mr. Pourshian alleges, claiming that he is the owner of copyright in his original screenplay, live theatrical production, and short film, each of which are titled “Inside Out“, and that Pixar infringed those copyrights “by production, reproduction, distribution and communication to the public by telecommunication of the film INSIDE OUTâ€.

This case is more akin to Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73 (CanLII), where the infringement claim did not involve direct cut-and-paste copying, but rather was based on an assessment of the cumulative effect of the features copied from the original work, to determine whether those features amount to a substantial part of the skill and judgment of the original author, expressed in the original work as a whole. This involves a review of whether there is substantial copying of elements like particular visual elements of setting and character, content, theme and pace. Compare this one with Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc. (Anne with a © : Copyright infringement and the setting of a Netflix series).

The Pourshian case was a preliminary motion about whether the claim can proceed in Canada, or whether it should be heard in the US. The Court found that there was a real and substantial connection in relation to the claims and Ontario, and the case will be permitted to continue against Pixar Animation Studios, Walt Disney Pictures Inc. and Disney Shopping Inc.

If this case proceeds to trial, it will be fascinating to watch.

Mr. Pourshian did pursue a separate claim in California (Pourshian v. Disney, Case No. 5:18-cv-3624), which was voluntarily withdrawn in 2018.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAnne with a © : Copyright infringement and the setting of a Netflix series

By Richard Stobbe

Is there copyright in the setting of a Netflix series?

It’s time for a dose of stereotypical Canadian culture, and you can’t do much better than another copyright battle over Anne of Green Gables! With Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc., 2019 ONSC 9 (CanLII) we can add to the  long list of cases surrounding the fictional character Anne. This newest case deals with a copyright claim by Sullivan Entertainment against the producers of a CBC / Netflix version entitled “ANNE with an E†(2017).

First, a newsflash: The Anne of Green Gables books were written by Lucy Maud Montgomery and originally published beginning in 1908.

Sullivan, of course, is known as the producer of a popular television version of the Anne of Green Gables novels, starting with “Anne of Green Gables†(1985), the copyright in which is registered under Canadian Copyright Registration No. 358612.

Enter the latest incarnation of the AGG story, a CBC series produced by Northwood Media, now streaming on Netflix.

Sullivan alleges that Northwood, the producer of the latest Netflix version, has copied certain elements that were created by Sullivan in its TV series from the 1980s, elements that were not in the original novels. This copyright claim forces an examination of the scope or range of copying that is permitted around setting, plot concepts, imagery, and production or design elements.

Wait… are plot concepts and settings even protectable? In copyright law, we know that ideas are not, on their own, protectable; copyright protects the expression of ideas. Here, Sullivan as the owner of the copyright in its television production alleges that the Netflix series infringes copyright by copying scenes, not literally but through non-literal copying of a substantial part of the original protected work.

For example, Sullivan alleges that the Netflix version copies settings or conceptual elements such as:

- the decision to set the story in the late 1890s (the choice made in the Sullivan version), as opposed to the 1870s (the choice made by the original author in the Anne of Green Gables novel).

- the use of steam trains, replicated from a scene in one of the Sullivan episodes (apparently steam trains would not have been historically accurate in a 1870s setting);

- copying the concept and scene of a class spelling bee, to establish the rivalry between Anne Shirley and Gilbert Blythe;

- depictions and staging of scenes such as Anne’s life with the Hammond family or Matthew Cuthbert passing by the hose of Mrs. Lynde’s on his way to the train station to pick up Anne.

The allegations are not that the scenes are literally cut-and-paste from the original, but that the copying of settings, concepts and staging is copying of “a substantial part” of the original for the purposes of establishing copyright infringement.

In the words of the court in Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73, copyright can protect “a feature or combination of features of the work, abstracted from it rather than forming a discrete part…. [T]he original elements in the plot of a play or novel may be a substantial part, so that copyright may be infringed by a work which does not reproduce a single sentence of the original.â€

(See our earlier article: Â Supreme Court on Copyright Infringement & Protection of Ideas )

The preliminary decision in Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc. is about a pre-trial procedure related to document discovery, and once it goes to trial, the outcome will be interesting to see. This case is a series worth watching.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsMeeting Mike Tyson does not constitute consideration for Canadian copyright assignment

By Richard Stobbe

When is a contract really a contract and when is it just a type of unenforceable promise that can be revoked or cancelled?

Glasz c. Choko, 2018 QCCS 5020 (CanLII) is a case about ownership of raw documentary footage of Mike Tyson, the well-known boxer, and whether an email exchange was enough to form a binding contract between a promoter and a filmmaker.

The idea of “consideration” is supposed to be one of the important elements of an enforceable contract. There must be something of value exchanging hands between two parties as part of a contract. But that “something of value” can take many forms. The old English cases talk about a mere peppercorn as sufficient consideration.

In this case, a boxing the promoter, Mr. Choko, promised a pair of filmmakers that he had a special relationship with Mike Tyson, and could give them special access to obtain behind-the-scenes footage of Mr. Tyson during his visit to Toronto in 2014. An email was exchanged on September 4, 2014, in which the filmmakers agreed that, in exchange for gaining this access, the copyright in the footage would be owned by the promoter, Mr. Choko.

The filmmakers later revoked their assignment.

The parties sued each other for ownership of the footage. Let’s unpack this dispute: the footage is an original cinematographic work within the meaning of section 2 of the Copyright Act. The issues are: Was the work produced in the course of employment? If not, was the copyright ownership to the footage assigned to Mr. Choko by virtue of the Sept. 4th email? And were the filmmakers entitled to cancel or revoke that assignment?

There was no employment relationship, that much was clear. And the filmmaker argued that the agreement was not an enforceable contract since there was a failure of consideration, and that the promoter misrepresented the facts when he insisted on owning the footage personally. In fact, he misrepresented how well he really knew the Tyson family, and mislead the filmmakers when he said that Mrs. Tyson has specifically requested that the promoter should be the owner of the footage. She made no such request.

The promoter, Mr. Choko, argued that these filmmakers would never had the chance to meet Mike Tyson without his introduction: thus, the experience of meeting Mr. Tyson should be enough to meet the requirement for “consideration†in exchange for the assignment of copyright. However, the court was not convinced: “every creative work can arguably be said to involve an experience…” If we accepted an “experience” as sufficient consideration then there would never be a need to remunerate the author for the assignment of copyright in his or her work, since there would always be an experience of some kind.

Take note: Meeting Mr. Tyson was insufficient consideration for the purposes of an assignment Canadian copyright law.

For advice on copyright issues, whether or not involving Mr. Tyson, please contact Richard Stobbe.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsCryptocurrency Decision: Enforcing Blockchain Rights

.

By Richard Stobbe

A seemingly simple dispute lands on the desk of a judge in Vancouver, BC. By analogy, it could be described like this:

- AÂ Canadian purchased 530 units of foreign currency #1 from a Singapore-based currency trader.

- By mistake, the currency trader transferred 530 units of currency #2 to the account of the Canadian.

- It turns out that 530 units of currency #1 are worth $780.

- You guessed it, 530 units of currency #2 are worth $495,000.

- Whoops.

- The Singaporean currency trader immediately contacts the Canadian and asks that the currency be returned, to correct the mistake.

Seems simple, right? The Canadian is only entitled to keep the currency worth $780, and he should be ordered to return the balance.

Now, let’s complicate matters somewhat. The recent decision in Copytrack Pte Ltd. v Wall, 2018 BCSC 1709 (CanLII), one of the early decisions dealing directly with blockchain rights, addresses this scenario but with a few twists:

Copytrack is a Singapore-based company which has established a service to allow copyright owners, such as photographers, to enforce their copyrights internationally. Copyright owners do this by registering their images with Copytrack, and then deploying software to detect instances of online infringement. When infringement is detected, the copyright owner extracts a payment from the infringer, and Copytrack earns a fee. This copyright enforcement business is not new. However, riding the wave of interest in blockchain and smart contracts, Copytrack has launched a new blockchain-based copyright registry coupled with a set of cryptocurrency tokens, to permit the tracking of copyrights using a blockchain ledger, and payments using blockchain-based cryptocurrency.  Therefore, instead of traditional fiat currency, like US dollars and Euros, which is underpinned by a highly regulated international financial services industry, this case involves different cryptocurrency tokens.

When Copytrack started selling CPY tokens to support their new system, a Canadian, Mr. Wall, subscribed for 580 CPY tokens at a price of about $780. Copytrack transferred 580 Ether tokens to his online wallet by mistake, enriching the account with almost half a million dollars worth of cryptocurrency. Mr. Wall essentially argued that someone hacked into his account and transferred those 530 Ether tokens out of his virtual wallet. Since he lacked control over those units of cryptocurrency, he was unable to return them to Copytrack.

The argument by Copytrack was based in an old legal principle of conversion – this is the idea that an owner has certain rights in a situation where goods (including funds) are wrongfully disposed of, which has the effect of denying the rightful owner of the benefit of those goods. With a stretch, the court seemed prepared to apply this legal principle to intangible cryptocurrency tokens, even though the issue was not really argued, legal research was apparently not presented, the proper characterization of cryptocurrency tokens was unclear to the court, the evidentiary record was inadequate, and in the words of the judge the whole thing “is a complex and as of yet undecided question that is not suitable for determination by way of a summary judgment application.”

Nevertheless, the court made an order on this summary judgement application. Perhaps this illustrates how usefully flexible the law can be, when it wants to be. The court ordered “that Copytrack be entitled to trace and recover the 529.8273791 Ether Tokens received by Wall from Copytrack on 15 February 2018 in whatsoever hands those Ether Tokens may currently be held.”

How, exactly, this order will be enforced remains to be seen. It is likely that the resolution of this particular dispute will move out of the courts and into a private settlement, with the result that these issues will remain complex and undecided as far as the court is concerned. A few takeaways from this decision:

- As with all new technologies, the court requires support and, in some cases, expert evidence, to understand the technical background and place things in context. This case is no different, but the comments from the court suggest something was lacking here: “Nowhere in its submission did Copytrack address the question of whether cryptocurrency, including the Ether Tokens, are in fact goods or the question of if or how cryptocurrency could be subject to claims for conversion and wrongful detention.”

- It is interesting to note that blockchain-based currencies, such as the CPY and Ether tokens at issue in this case, are susceptible to claims of hacking. “The evidence of what has happened to the Ether Tokens since is somewhat murky”, the court notes dryly. This flies in the face of one of the central claims advanced by blockchain advocates: transactions are stored on an immutable open ledger that tracks every step in a traceable, transparent and irreversible record. If the records are open and immutable, how can there be any confusion about these transfers? How do we reconcile these two seemingly contradictory positions? The answer is somewhere in the ‘last mile’ between the ledgerized tokens (which sit on a blockchain), and the cryptocurrency exchanges and virtual wallets (using ‘non-blockchain’ user-interface software for the trading and management of various cryptocurrency accounts). It may be infeasible to hack blockchain ledgers, but it’s relatively feasible to hack the exchange or wallet. This remains a vulnerability in existing systems.

- Lastly, this decision is one of the first in Canada directly addressing the enforcement of rights to ownership of cryptocurrency. Clearly, the law in this area requires further development – even in answering the basic questions of whether cryptocurrency qualifies as an asset covered by the doctrines of conversion and detinue (answer: it probably does). This also illustrates the requirement for traditional dispute resolution mechanisms between international parties, even in disputes involving a smart-contract company such as Copytrack. The fine-print in agreements between industry players will remain important when resolving such disputes in the future.

Seek experienced counsel when confronting cryptocurrency issues, smart contracts and blockchain-based rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAI and Copyright and Art

.

By Richard Stobbe

At the intersection of this Venn diagram  [ Artificial Intelligence + Copyright + Art ] lies the work of a Paris-based collective.

By means of an AI algorithm, these artists have generated a series of portraits that have caught the attention of the art world, mainly because Christie’s, the auction house,  has agreed to place these works of art on the auction block. Christie’s markets themselves as “the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm”. The series of portraits is notionally “signed” (ð’Žð’Šð’ ð‘® ð’Žð’‚ð’™ ð‘« ð”¼ð’™ [ð’ð’ð’ˆ ð‘« (ð’™))] + ð”¼ð’› [ð’ð’ð’ˆ(ðŸ − ð‘«(ð‘®(ð’›)))]), denoting the algorithm as the author.

We have an AI engine that was programmed to analyze a range of prior works of art and create a new work of art. So where does this leave copyright? Clearly, the computer software that generated the artwork was authored by a human; whereas the final portrait (if it can be called that) was generated by the software. Can a work created by software enjoy copyright protection?

While Canadian courts have not yet tackled this question, the US Copyright Office in its Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices has made it clear that copyright requires human authorship: “…when a work is created with a computer program, any elements of the work that are generated solely by the program are not registerable…”

This is reminiscent of the famous “Monkey Selfie” case that made headlines a few years ago, where the Copyright Office came to the same conclusion: without a human author, there’s no copyright.

Calgary – 0:700 MST

Photo Credit: Obvious Art

No comments

Artist Sues for Infringement of “Moral Rights”

By Richard Stobbe

AÂ professional photographer sued the gallery that sold his works, and won a damage award for copyright infringement, infringement of moral rights, and punitive damages. In this case (Collett v. Northland Art Company Canada Inc., 2018 FC 269 (CanLII)), Mr. Collett, the photographer, alleged that his former gallery, Northland, infringed his rights after their business relationship broke down.

We don’t see many “moral rights” infringement cases in Canada, so this case is of interest for artists and other copyright holders for this reason alone. What are “moral rights”?

In Canada the Copyright Act tells us that the author of a work has certain rights to the integrity of the work, the right to be associated with the work as its author by name or under a pseudonym and the right to remain anonymous.

These so-called moral rights of the author to the integrity of a work can be infringed where the work is “distorted, mutilated or otherwise modified” ina way that compromises or prejudices the author’s honour or reputation, or where the work is used in association with a product, service, cause or institution that harms the authors reputation. Determining infringement has a highly subjective aspect, which must be established by the author. But this type of claim also has an objective element requiring a court to evaluate the prejudice or harm to the author’s “honour or reputation” which can be supported by public or expert opinion.

Here, the court found that the gallery had infringed Mr. Collett’s moral rights when the gallery intentionally reproduced one print entitled “Spirit of Our Land†and attributed the work to another artist. By reproducing “Spirit of Our Land†without Mr. Collett’s permission, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in the work. By attributing the reproductions to another artist, the gallery infringed the artist’s moral right “to be associated with the work as its authorâ€. This is actually a useful illustration of the difference between these different types of artist’s rights.

The unauthorized reproductions sold by the gallery were apparently taken from a copy resulting in images of lower resolution and therefore inferior quality, compared to authorized prints; unfortunately, we don’t have any insight into whether inferior quality would also infringed the artist’s moral right to the integrity of the work. The court declined to comment on this aspect since it had already concluded that moral rights were infringed when the prints were sold under the name of another artist.

Lastly, and interestingly, the court found that a link from the gallery’s site to the artist’s website constituted an infringement of copyright. It’s difficult to see how a link, without more, could constitute a reproduction of a work, unless the linked site was somehow framed or otherwise replicated within the gallery’s site. The evidence is not clear from reading the decision but the artist’s allegation was that the gallery “reproduced the entirety” of certain pages from the artist’s site, which created the false impression that the gallery still represented the artist. The court noted that the gallery continued to maintain a link to Mr. Collett’s website “knowing it was not authorized to do so.” By doing so, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in his site, including a reproduction of certain prints. Maintaining such a link was not found to constitute a breach of the artist’s moral rights.

In the end, statutory damages of $45,000 were awarded for breach of copyright, $10,000 for infringement of moral rights, and $25,000 for punitive damages to punish the gallery for its planned, deliberate and ongoing acts of infringement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 3)

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1 and Part 2, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

In the final part, we review the next couple of areas:

- Copyright

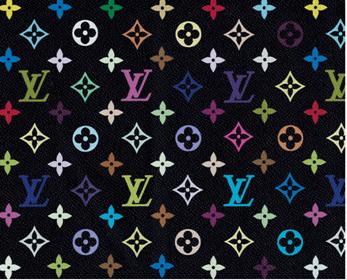

Copyright is a very flexible and wide-ranging tool to use in the fashion and apparel industry.  Under the Copyright Act, a business can use copyright to protect original expression in a range of products including artistic works, fabric designs, two and three-dimensional forms, and promotional materials, such as photographs, advertisements, audio and video content. For example, in Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. et al. and Singga Enterprises (Canada) Inc., the Federal Court sent a strong message to counterfeiters. This was a case of infringement of copyright , arising from the sale of counterfeit copies of Louis Vuitton and Burberry handbags through online sales and operations in Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton. Louis Vuitton owns copyright in the following Multicolored Monogram Print pattern:

Since the Copyright Act provides for an award of both damages and profits from the sale of infringing goods, or statutory damages between $500 to $20,000 per infringed work, the copyright owner had a range of options available to enforce its IP rights. In this case, the Federal Court awarded Louis Vuitton and Burberry a total of over $2.4 million in damages against the defendants, catching both the corporate and personal defendants in the award.

- Personality Rights

In Canada, the use of a famous person’s personality for commercial gain without authorization can lead to liability for “misappropriation of personalityâ€. To establish a case of misappropriation of personality, three elements must be shown:

- The exploitation of personality is for a commercial purpose.

- The person in question is identifiable in the context; and

- The use of personality suggests some endorsement or approval by the person in question.

Just ask William Shatner who objected on Twitter when his name and caricature were used to promote a condo development in Ontario, in a way that suggested that he endorsed the project.

Canadian personality rights benefit from some protection at the federal level through the Trademarks Act and the Competition Act, and are protected in some provinces. B.C., Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec have privacy statutes that restrict the unauthorized commercial use of personality, although the various provincial statutes approach the issue slightly differently. Specific advice is required in different jurisdictions, depending on the circumstances.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright in Architectural Works: an update

By Richard Stobbe

Who owns the copyright in a building?  A few years ago, we looked at the issue of Copyright in House Plans, but let’s look at something bigger. Much bigger.

In Lainco inc. c. Commission scolaire des Bois-Francs, 2017 CF 825, the federal court reviewed a claim by an architectural engineering firm over infringement of copyright in the design for an indoor soccer stadium.

Lainco, the original engineers, sued a school board, an engineering firm, a general contractor and an architect, claiming that this group copied the unique design of Lainco’s indoor soccer complex. The nearly identical copycat structure built in neighbouring Victoriaville was considered by the court to be an infringement of the original Lainco design even though the copying covered functional elements of the structure. The court decided that such functional structures can be protected as “architectural works†under the Copyright Act, provided they comprise original expression, based on the talent and judgment of the author, and incorporate an architectural or aesthetic element.

The group of defendants were jointly and severally liable for the infringement damage award, which was assessed at over $700,000.

Make sure you clarify ownership of copyright in architectural designs with counsel to avoid these pitfalls.

Calgary – 07:00

No comments

Bozo’s Flippity-Flop and Shooting Stars: A cautionary tale about rights management

By Richard Stobbe

If you’ve ever taken piano lessons then titles like “Bozo’s Flippity-Flop”, “Shooting Stars” and “Little Elves and Pixies” may be familiar.

These are among the titles that were drawn into a recent copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the Royal Conservatory against a rival music publisher for publication of a series of musical works. In Royal Conservatory of Music v. Macintosh (Novus Via Music Group Inc.) 2016 FC 929, the Royal Conservatory and its publishing arm Frederick Harris Music sought damages for publication of these works by Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music.

The case serves as a cautionary tale about records and rights management, since much of the confusion between the parties, and indeed within the case itself, could be blamed on missing or incomplete records about who ultimately had the rights to the musical works at issue. In particular, a 1999 agreement which would have clarified the scope of rights, was completely missing. The court ultimately determined that there was no evidence that the defendants Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music could benefit from any rights to publish these songs; the missing 1999 agreement was never assigned or extended to the defendants.

In assessing damages for infringement, the court reviewed the factors set forth in the Copyright Act, including:

- Â the good faith or bad faith of the defendant;

- Â the conduct of the parties before and during the proceedings;

- Â the need to deter other infringements of the copyright in question;

- Â in the case of infringements for non-commercial purposes, the need for an award to be proportionate to the infringements, in consideration of the hardship the award may cause to the defendant, whether the infringement was for private purposes or not, and the impact of the infringements on the plaintiff.

In evaluating the deterrence factor, the court noted: “it is unclear what effect a large damages award would have in deterring further copyright infringement, when the infringement at issue here appears to be the product of poor record-keeping and rights management on the part of both parties.  If anything, this case is instructive that the failure to keep crucial contracts muddies the waters around rights, and any resulting infringement claims. The Respondents should not alone bear the brunt of this laxity, because the Applicants played an equal part in the inability to provide to the Court the key document at issue.” [Italics added]

For these reasons, the court set per work damages at the lowest end of the commercial range ($500 per work), for a total award of $10,500 in damages.

Calgary – o7:00 MST

No commentsArtist Sues Starbucks Claiming Copyright Infringement

New York artist Maya Hayuk was approached by an advertising agency working for Starbucks, to see if she would assist them with a proposed advertising campaign. Ms. Hayuk is known internationally for her paintings using bold colors, and vibrant geometric shapes – rays, lines, stripes and circles.

She declined the offer to work with Starbucks (too busy) and was surprised when she saw the final marketing campaign for the Starbucks Frappuccino product. The marketing materials, including artwork on Frappuccino cups, websites, and on signage at Starbucks’ retail locations and promotional videos, were strikingly similar to Hayuk’s artworks. The artist promptly launched a copyright infringement lawsuit against both Starbucks and its advertising agency, claiming that Starbucks created artwork that was substantially similar to her paintings and further, the Starbucks material appropriated the “total concept and feel†of her paintings, even though there was no “carbon copy” of any particular painting.

Last week, A US District Court handed down its decision in Hayuk v. Starbucks Corp and 71andSunny Partners LLC (PDF) (Case No. 15cv4887-LTS SDNY). It is well settled that copyright does not protect an artist’s style or elements of her ideas. The court denied the claim that any copyright infringement occurred. In analyzing the two images, the court notes that the proper analysis is not to dissect, crop or rotate particular elements or pieces of the two works and lay the isolated parts side-by-side, but rather to look at substantial similarity of the works as a whole. The court concluded that “Although the two sets of works can be said to share the use of overlapping colored rays in a general sense, such elements fall into the unprotectible category of ‘raw materials’ or ideas in the public domain.” [Emphasis added] Thus, there could be no finding of substantial similarity and the claims were dismissed.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsMaking a Monkey Out of Copyright

By Richard Stobbe

The Monkey Selfie Caper apparently has legs, as they say in the news business. Long legs with opposable toes. (For background, see our earlier post: Monkey See, Monkey Do… However Monkey Does Not Enjoy Copyright Protection )

On September 21, PETA announced that it had filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in U.S. federal court in San Francisco. PETA is suing “the owner of the camera, photographer David J. Slater and his company, Wildlife Personalities Ltd., which both claim copyright ownership of the photos that Naruto indisputably took. Also named as a defendant is the San Francisco–based publishing company Blurb, Inc., which published a collection of Slater’s photographs, including two selfies taken by Naruto. The lawsuit seeks to have Naruto declared the “author†and owner of his photograph. … U.S. copyright law doesn’t prohibit an animal from owning a copyright, and since Naruto took the photo, he owns the copyright, as any human would.”

On September 21, PETA announced that it had filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in U.S. federal court in San Francisco. PETA is suing “the owner of the camera, photographer David J. Slater and his company, Wildlife Personalities Ltd., which both claim copyright ownership of the photos that Naruto indisputably took. Also named as a defendant is the San Francisco–based publishing company Blurb, Inc., which published a collection of Slater’s photographs, including two selfies taken by Naruto. The lawsuit seeks to have Naruto declared the “author†and owner of his photograph. … U.S. copyright law doesn’t prohibit an animal from owning a copyright, and since Naruto took the photo, he owns the copyright, as any human would.”

Yes, you heard that right, the crested macaque is the plaintiff in a copyright infringement lawsuit. April 1st is still 5 months away, but with luck the federal court will have ruled on some preliminary motions by then.

Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

2 commentsCanadian Copyright Term Extensions

By Richard Stobbe

As we noted in our earlier post (See: this link) the bill known as Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1 was tabled in the House of Commons on May 7, 2015. It passed Second Reading in the House of Commons on May 25th and is now with the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance.

The bill proposes to amend the Copyright Act to extend the term of copyright protection for sound recordings and performances fixed in sound recordings.

Copyright in a sound recording currently subsists until the end of 50 years after the end of the calendar year in which the first fixation of the sound recording occurs. However, if the sound recording is published before the copyright expires, then copyright protection would be extended to the earlier of the end of 70 years after the end of the calendar year in which the first publication of the sound recording occurs and the end of 100 years after the end of the calendar year in which that first fixation occurs.

The bill is expected to pass. Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsCopyright Implications of a “Right to be Forgotten”? Or How to Take-Down the Internet Archive.

–

By Richard StobbeÂ

They say the internet never forgets. From time to time, someone wants to challenge that dictum.

In our earlier posts, we discussed the so-called “right to be forgotten” in connection with a Canadian trade-secret misappropriation and passing-off case and an EU privacy case. In a brief ruling in October, the Federal Court reviewed a copyright claim that fits into this same category. In Davydiuk v. Internet Archive Canada, 2014 FC 944 (CanLII), the plaintiff sought to remove certain pornographic films that were filmed and posted online years earlier. By 2009, the plaintiff had successfully pulled down the content from the original sites on which the content had been hosted. However, the plaintiff discovered that the Internet Archive’s “Wayback Machine” had crawled and retained copies of the content as part of its archive.

If you’re not familiar with the Wayback Machine, here is the court’s description: “The ‘Wayback Machine’ is a collection of websites accessible through the websites ‘archive.org’ and ‘web.archive.org’. The collection is created by software programs known as crawlers, which surf the internet and store copies of websites, preserving them as they existed at the time they were visited. According to Internet Archive, users of the Wayback Machine can view more than 240 billion pages stored in its archive that are hosted on servers located in the United States. The Wayback Machine has six staff to keep it running and is operated from San Francisco, California at Internet Archive’s office. None of the computers used by Internet Archive are located in Canada.”

The plaintiff used copyright claims to seek the removal of this content from the Internet Archive servers, and these efforts included DMCA notices in the US. Ultimately unsatisfied with the results, the plaintiff commenced an action in Federal Court in Canada based on copyrights. The Internet Archive disputed that Canada was the proper forum: it argued that California was more appropriate since all of the servers in question were located in the US and Internet Archive was a California entity.

Since Internet Archive raised a doctrine known as “forum non conveniens”, it had to convince the court that the alternative forum (California) was “clearly more appropriate†than the Canadian court. It is not good enough to simply that there is an appropriate forum elsewhere, rather the party making this argument has to show that clearly the other forum is more appropriate, fairer and more efficient. The Federal Court was not convinced, and it concluded that there was a real and substantial connection to Canada. The case will remain in Canadian Federal Court. A few interesting points come out of this decision:

- This is not a privacy case. It turns upon copyright claims, since the plaintiff in this case had acquired the copyrights to the original content. Nevertheless, the principles in this case (to determine which court is the proper place to hear the case) could be applied to any number of situations, including privacy, copyright or personality rights.

- Interestingly, the fact that the plaintiff had used American DMCA notices did not, by itself, convince the court that the US was the best forum for this case.

- The court looked to a recent trademark decision (Homeaway.com Inc. v. Hrdlicka) to show that a trademark simply appearing on the computer screen in Canada constituted use and advertising in Canada for trademark law purposes. Here, accessing the content in Canada from servers located in the US constituted access in Canada for copyright purposes.

- While some factors favoured California, and some favoured Canada, the court concluded that California was not clearly more appropriate. This shows there is a first-mover advantage in commencing the action in the preferred jurisdiction. Â

Get advice on internet copyright claims by contacting our Intellectual Property & Technology Group.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

Â

No commentsOwnership of Photograph by Employee

–

By Richard Stobbe

While our last post dealt with the creation of photographs and other works of authorship by primates, robots and divine beings, this story is a little more grounded in facts that you might see in the average work day.

When an employee takes a photograph, who owns copyright in the image?

In Mejia v. LaSalle College International Vancouver Inc., 2014 BCSC 1559, a BC court reviewed this question in the context of an employment-related complaint (there were other issues including wrongful dismissal and defamation which we won’t go into). Here, an instructor at LaSalle College in Vancouver took a photograph, and later alleged that the college infringed his copyright in the picture after he discovered that it was being used on LaSalle’s Facebook page.

The main issue was whether the picture was taken in the course of employment. The instructor argued that the photograph was taken during his personal time, on his own camera. He tendered evidence from camera metadata to establish the details of the camera, time and date. He argued that s. 13(3) of the Copyright Act did not apply because he was not employed to take photos. He sought $20,000 in statutory damages. The college argued that the photo was taken of students in the classroom and was within the scope of employment, and copyright would properly belong to the college as the employer, under s. 13(3) of the Act.

The court, after reviewing all of this, decided that the instructor was not hired as a photographer. While an instructor could engage in a wide variety of activities during his employment activities, the court decided that “the taking of photographs was not an activity that was generally considered to be within the duties of the plaintiff instructor, and there was no contractual agreement that he do so.” It was, in short, not connected with the instructor’s employment. In the end, the photograph was not made in the course of employment. Therefore, under s. 13(1) of the Copyright Act, the instructor was the first owner of copyright, and the college was found to have infringed copyright by posting it to Facebook.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsMonkey See, Monkey Do… However Monkey Does Not Enjoy Copyright Protection

By Richard Stobbe

I know this story crested a few weeks ago, but who can resist it? A famous 1998 Molson Canadian ad posed a Canadian version of the infinite monkey theorem. The cheeky ad, showing a seemingly endless array of monkeys on typewriters, sidestepped the more important question about whether the monkeys as authors would enjoy copyright protection over the works they created.

A wildlife photographer’s dispute with Wikimedia over ownership of photographs taken by primates in Indonesia has brought international attention to this pressing issue. The “Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition†now explicitly states that photographs by monkeys are not eligible for copyright protection. Nor are elephant-paintings deserving of copyright. “Likewise,” the Compendium notes dryly, “the Office cannot register a work purportedly created by divine or supernatural beings.” Robots are also out of luck.

There is no word on whether Canada is directly addressing this question.

Calgary – 09:00 MST

No commentsCopyright Litigation and the Risk of Double Costs

–

By Richard Stobbe

An American photojournalist, Ms. Leuthold, was on the scene in New York City on September 11, 2001. She licensed a number of still photographs to the CBC for use in a documentary about the 9/11 attacks. The photos were included in 2 versions of the documentary, and the documentary was aired a number of times betwen 2002 and 2004. We originally wrote about this in an earlier post: Copyright Infringement & Licensing Pitfalls. The court found that the CBC had infringed copyright in the photographs in six broadcasts which were not covered by the licenses. Though Leuthold claimed damages of over $20 million, only $20,000 was awarded as damages by the court.

In Leuthold v. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2014 FCA 174, the Federal Court of Appeal upheld an award of double costs against Leuthold. Early in the litigation process, the CBC had formally offered to settle for $37,500 plus costs. Ms. Leuthold did not accept the CBC’s offer and went to trial where she was awarded $20,000. Ms. Leuthold’s total recovery was substantially less that the amount of the CBC’s offer. When this happens, a plaintiff can be liable under Rule 420 for double costs, which was awarded in this case. Double costs amounted to approximately $80,000 in these circumstances, which means Ms. Leuthold is liable for about 4 times the amount of the damage award. Although Ms. Leuthold objected that such a disproportionate costs award was “punitive”, the court concluded:

“The sad fact of the matter is that litigation produces winners and losers; that is why it is such a blunt tool in the administration of justice. But justice is not served by allowing persons who have imposed costs on others by pursuing or defending a claim which lacks merit to avoid the consequences of their behaviour. Such a policy would be more likely to bring the administration of justice into disrepute than the result in this case.”

For copyright litigation and licensing advice, contact the Field Law Intellectual Property & Technology Group.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsSupreme Court on Copyright Infringement & Protection of Ideas

Let’s say you pitch a story idea to a TV production company – and not just an idea, but a complete set of storyboards, characters and scripts. You would be surprised if one day you saw that story idea come to life in a TV production that gave no credit to you as the orginal creator of the materials. That’s what happened to Claude Robinson and his idea for a children’s TV program inspired by Robinson Crusoe.

One of the most important copyright decisions in 2013 was issued by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) in late December: In Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73, the court reviewed Mr. Robinson’s claim that Cinar Corp. infringed copyright in his original story materials by copying a substantial part of those materials in the new TV production called “Robinson Sucroë”.

I am often asked when or why someone can copy the ideas of someone else. Ideas themselves are not protected by copyright law. Many features of a TV show or a movie are simply non-protectable, including ideas, elements drawn from the public domain or generic components of a story, like heroes, villains, conflict and resolution. However, in this case, the idea was articulated and expressed in a set of original written materials which resulted from the skill and judgement of the author.

The court framed this fascinating issue in this way: “The need to strike an appropriate balance between giving protection to the skill and judgement exercised by authors in the expression of their ideas, on the one hand, and leaving ideas and elements from the public domain free for all to draw upon, on the other, forms the background against which the arguments of the parties must be considered.”

In the end, the court rejected the notion that the two works must be compared piecemeal to determine if protectable elements of the original work were similar to the copy. Instead, the court reviewed the “cumulative effect” of the features copied from the original, to determine if those features amount to a substantial part of the original work as a whole. Thus the court approved a “qualitative and holistic assessment of the similarities between the works”, rather than dissecting both works to compare individual features in isolation.

This decision will be applied in other copyright infringement situations in Canada, including art, media, music and software.

Calgary – 05:00 MST

2 commentsApp Developer Wins in SCRABBLE Battle

–

Zynga, the world’s largest app-developer has scored a win against the owner of the SCRABBLE brand. This case brings up several interesting points about international trade-mark protection in the era of apps.

The well known SCRABBLE® brand is a registered trade-mark owned by different owners in different parts of the world. Hasbro Inc. owns the intellectual property rights in the U.S.A and Canada. In the rest of the world, the brand is owned by J.W. Spear & Sons Limited, a subsidiary of Mattel Inc. Mattel is not affiliated with Hasbro – in fact, the two companies are long-time rivals.

In JW Spear v. Zynga, a UK court has decided that the use of the SCRAMBLE brand by Zynga for its word-based app game does not infringe the SCRABBLE trade-mark in the UK, nor does it constitute passing-off. However, the court did consider Zynga’s SCRAMBLE logo design (above left) to constitute an infringement, since the stylized M appears at first glance to resemble a letter B. A few interesting points on this long-running battle:

- As we’ve seen in other IP disputes covered by ipblog, this litigation is part of a wider dispute in multiple jurisdictions, including France and Germany.

- Mattel was chastised by the court for its delay in responding to Zynga’s earlier use of the SCRAMBLE mark, in late 2007. This delay influenced the court’s conclusion that Mattel did not truly perceive SCRAMBLE to be a threat to the SCRABBLE mark. This in turn influenced the court’s opinion that the public would not be confused by the use of the 2 marks.

- Mattel’s delay was likely caused by the efforts of the parties to negotiate a license agreement to produce a physical board-game version of the SCRAMBLE app.  The litigation followed a break-down in negotiations, when Zynga concluded a deal with Mattel’s rival Hasbro.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsClick Here to Transfer Copyright

–

When you upload your pictures to a website, you might click through some terms of use…Did you just transfer ownership of the copyright in your pictures?

In a recent US case (Metropolitan Regional Information Systems, Inc. v. American Home Realty Network, Inc., No. 12-2102, Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals) the court dealt with a copyright infringement claim over photos uploaded to a real estate website. Users were required to click-through the website terms of use (TOU) prior to uploading, and those terms clearly indicated that copyright in the images was transferred to the website owner.

In the course of the infringement lawsuit, this was challenged, so the court had to squarely address the question of whether copyright can be validly transferred via online terms. “The issue we must yet resolve,” said the Court, “is whether a subscriber, who ‘clicks yes’ in response to MRIS’s electronic TOU prior to uploading copyrighted photographs, has signed a written transfer of the exclusive rights of copyright ownership in those photographs consistent with” the Copyrght Act.

In Canada, the equivalent section of the Act says “The owner of the copyright in any work may assign the right, either wholly or partially …but no assignment or grant is valid unless it is in writing signed by the owner of the right…”.

The Court in the Metropolitan Regional case decided that yes, an electronic agreement in this case was effective to transfer copyright for the purposes of the Copyright Act.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsThe Bluenose Copyright Fight

When it comes to Canadian IP battles, neither The Great Olympic Sweater Debate nor the Distinctly Canadian Patent Fight can rival the court battle over the design of the Bluenose for sheer Canadianess.

In Nova Scotia v. Roué, 2013 NSCA 94 (CanLII) the court addressed the copyright in the design of the famous schooner Bluenose. This is the ship that graces the back of the Canadian dime. Certain descendants of the vessel’s original designer, William J. Roué, launched an action against the Province of Nova Scotia, claiming that the Province was infringing copyright and moral rights in the original design drawings of their ancestor, by restoring or rebuilding the Bluenose vessel.

A little history is in order: The original Bluenose was launched in 1921. A legendary racing schooner, the ship was undefeated for 17 years straight. The original Bluenose sank on a reef off Haiti in 1946. A replica Bluenose II was constructed in 1963, with access to Mr. Roué’s original designs. The Province took ownership in 1971 and now the Province describes its current efforts as a restoration of Bluenose II. Mr. Roué’s descendants allege that the Province is in fact creating an entirely new vessel and thus infringing copyright and moral rights in the original drawings. The Province responded by arguing, among other things, that the restoration of the Bluenose II is not a “substantial reproduction” of the original Bluenose, but rather an independent design, and if any of the original design was used “it was only dictated by the utilitarian function of the article”, and thus outside the purview of copyright.

As with many fascinating copyright battles, this one turned on relatively mundane court rules. Here, the application and the appeal centred on the question of whether the case could proceed as an application rather than by means of a full trial. Weighing all of the factors, the court suggested that the application could go ahead, without the need to convert it to a full trial. Stay on this tack… the case will continue.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No comments