Click-Through Agreements

.

By Richard Stobbe

Sierra Trading Post is an Internet retailer of brand-name outdoor gear, family apparel, footwear, sporting goods. Sierra lists comparison prices on its site to show consumers that its goods are competitively priced.

Chen, the plaintiff, sued Sierra, claiming the website’s comparison prices were false, deceptive, or misleading. The internet retailer defended by asserting that the lawsuit should be dismissed: Sierra pointed out that users of its site agreed to binding arbitration in the Terms of Use. Chen countered, arguing that he had never seen the Terms of Use and so they were not binding.

In Chen v. Sierra Trading Post, Inc., 2019 WL 3564659 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 6, 2019), a US court decision, the court reviewed the issues. There was no disagreement that the choice-of-law and arbitration clauses appeared in the Terms of Use. The question, as with so many of these cases, is around the set-up of Sierra’s check-out screen. Were the Terms of Use brought to the attention of the user, so that the user consented to those terms at the point of purchase, thus evidencing a mutual agreement between the parties to be bound by those terms?

Both Canadian and US cases have been tolerant of a range of possibilities for a check-out procedure, and the placement of “click-through” terms. This applies equally to e-commerce sites, software licensing, subscription services, or online waivers. Ideally, the terms are made available for the user to read at the point of checkout, and the user or consumer has a clear opportunity to indicate assent to those terms. In some cases, the courts have accepted terms that are linked, where assent is indicated by a check-box.

While there is no specific bright-line test, the idea is to make it as easy as possible for a consumer to know (1) that there are terms and (2) that they are taking a positive step to agree to those terms.

In this case, STP claimed that Chen would have had notice of the Terms of Use via the website’s “Checkout†page where, a few lines below the “Place my order†button, a line says “By placing your order you agree to our Terms & Privacy Policyâ€. The court noted that “The Consent line contains hyperlinks to STP’s TOU and Privacy Policy.”

On balance, the court agreed to uphold the Terms of Use and compel arbitration. While this was a win for Sierra, the click-through process could easily have been much more robust. For example, rather than “Place my order”, the checkout button could have said said “By Placing my order I agree to the Terms of Use” or a separate radio button could have been placed beside the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy to indicate assent.

Internet retailers, online service providers, software vendors and anyone imposing terms through click-through contracts should ensure that their check-out process is reviewed: make it as easy as possible for a court to agree that those terms are binding.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsClarity on IP Licenses and Bankruptcy

By Richard Stobbe

As we wrote about a year ago (See: What happens to IP on bankruptcy? ), we have been anticipating amendments to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) and Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) relating to IP licenses in cases where the IP licensor becomes insolvent. We now know that these changes will come into force November 1, 2019.

When it becomes law, Bill C-86 will enact changes to Canadian bankruptcy laws to clarify that intellectual property users can preserve their usage rights, even if:

- intellectual property rights are sold or disposed of in the course of a bankruptcy or insolvency proceeding, or

- if the trustee or receiver seeks to disclaim or cancel the license agreement relating to IP rights.

If the bankrupt company is an owner of IP, that owner has licensed the IP to a user or licensee, and the intellectual property is included in a sale or disposition by the trustee, the changes in Bill C-86 make it clear that the sale or disposition does not affect the licensee’s right to continue to use the IP during the term of the agreement. This is conditional on the licensee continuing to perform its obligations under the agreement in relation to the use of the intellectual property.

For more background, see:

Calgary 07:00 MST

No commentsLEGO vs. LEPIN: Battle of the Brick Makers!

By Richard Stobbe

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

The LEGO Group recently announced a win in Guangzhou Yuexiu District Court in China, based on unfair competition and infringement of its intellectual property rights in 3-dimensional artworks of 18 LEGO sets, and a number of LEGO Minifigures. This resulted in an injunction prohibiting the production, sale or promotion of the infringing sets, and a damage award of RMB 4.5 million.

While this decision is hailed as a win for LEGO, and a blow in favour of IP rights enforcement in China, the commercial reality is that 18 sets is a drop in the proverbial ocean of counterfeits for LEGO. A quick spin around the Lepin website shows that there is a sprawling product line available to the marketplace, most of which are direct copies of the corresponding LEGO sets. These are copies in appearance at least, since the quality of the Lepin product is … different, when compared to the quality of LEGO branded merchandise, according to some online reviews.

The connectable plastic brick which was popularized by LEGO is not, in itself, protectable from the IP perspective (patents expired long ago, and the trademarks in the brick shape were struck down in Canada). This permits entry by competitors such as MEGA-BLOKS, a company that sells a virtually identical interlocking brick, but under a distinctive brand, with original set designs, and rival licensing deals of its own Рfeaturing the likes of Pok̩mon, Sesame Street, John Deere and Star Trek.

While the bricks are just bricks, the LEGO trademarks are protectable, and as LEGO established, so are the rights in three-dimensional set designs, packaging art and other elements that were shamelessly copied by the busy folks at Lepin.

Protection of market share is a complex undertaking, where an intellectual property strategy is one element.  Looking for advice on how to protect your business using IP as a tool? Contact our IP advisors to start the conversation.

Related Reading: Battle of the Blocks (looking at the battle between Lego and Mega Blocks in Canada).

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

What happens to IP on bankruptcy?

By Richard Stobbe

The government introduced changes to some of the rules governing what happens to intellectual property on bankruptcy. If it becomes law, Budget Bill C-86 would enact changes to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) and the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) to clarify that intellectual property users can preserve their usage rights, even if:

- intellectual property rights are sold or disposed of in the course of a bankruptcy or insolvency proceeding, or

- if the trustee or receiver seeks to disclaim or cancel the license agreement relating to IP rights.

If the bankrupt company is an owner of IP, that owner has licensed the IP to a user or licensee, and the intellectual property is included in a sale or disposition by the trustee, the proposed changes in Bill C-86 make it clear that the sale or disposition does not affect the licensee’s right to continue to use the IP during the term of the agreement. This is conditional on the licensee continuing to perform its obligations under the agreement in relation to the use of the intellectual property.

The same applies if the trustee seeks to disclaim or resiliate the license agreement – such a step won’t impact the licensee’s right to use the IP during the term of the agreement as long as the licensee continues to perform its obligations under the agreement in relation to the use of the intellectual property.

These changes clarify and expand the 2009 rules in Section 65.11(7) of the BIA  and a similar provision in s. 32(6) of the CCAA. In particular, these amendments would extend the rules to cover sale, disposition, disclaimer or resiliation of an IP license agreement, whether by a trustee or a receiver.

This will solve the problem encountered in Golden Opportunities Fund Inc. v Phenomenome Discoveries Inc., 2016 SKQB 306 (CanLII), where the court noted that section 65.11(7) of the BIA was narrowly construed to only apply to trustees, and thus has no bearing on a court-appointed receivership.

Stay tuned for the progress of these proposed amendments.

Related Reading, if you’re into this sort of thing:

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentCryptocurrency Decision: Enforcing Blockchain Rights

.

By Richard Stobbe

A seemingly simple dispute lands on the desk of a judge in Vancouver, BC. By analogy, it could be described like this:

- AÂ Canadian purchased 530 units of foreign currency #1 from a Singapore-based currency trader.

- By mistake, the currency trader transferred 530 units of currency #2 to the account of the Canadian.

- It turns out that 530 units of currency #1 are worth $780.

- You guessed it, 530 units of currency #2 are worth $495,000.

- Whoops.

- The Singaporean currency trader immediately contacts the Canadian and asks that the currency be returned, to correct the mistake.

Seems simple, right? The Canadian is only entitled to keep the currency worth $780, and he should be ordered to return the balance.

Now, let’s complicate matters somewhat. The recent decision in Copytrack Pte Ltd. v Wall, 2018 BCSC 1709 (CanLII), one of the early decisions dealing directly with blockchain rights, addresses this scenario but with a few twists:

Copytrack is a Singapore-based company which has established a service to allow copyright owners, such as photographers, to enforce their copyrights internationally. Copyright owners do this by registering their images with Copytrack, and then deploying software to detect instances of online infringement. When infringement is detected, the copyright owner extracts a payment from the infringer, and Copytrack earns a fee. This copyright enforcement business is not new. However, riding the wave of interest in blockchain and smart contracts, Copytrack has launched a new blockchain-based copyright registry coupled with a set of cryptocurrency tokens, to permit the tracking of copyrights using a blockchain ledger, and payments using blockchain-based cryptocurrency.  Therefore, instead of traditional fiat currency, like US dollars and Euros, which is underpinned by a highly regulated international financial services industry, this case involves different cryptocurrency tokens.

When Copytrack started selling CPY tokens to support their new system, a Canadian, Mr. Wall, subscribed for 580 CPY tokens at a price of about $780. Copytrack transferred 580 Ether tokens to his online wallet by mistake, enriching the account with almost half a million dollars worth of cryptocurrency. Mr. Wall essentially argued that someone hacked into his account and transferred those 530 Ether tokens out of his virtual wallet. Since he lacked control over those units of cryptocurrency, he was unable to return them to Copytrack.

The argument by Copytrack was based in an old legal principle of conversion – this is the idea that an owner has certain rights in a situation where goods (including funds) are wrongfully disposed of, which has the effect of denying the rightful owner of the benefit of those goods. With a stretch, the court seemed prepared to apply this legal principle to intangible cryptocurrency tokens, even though the issue was not really argued, legal research was apparently not presented, the proper characterization of cryptocurrency tokens was unclear to the court, the evidentiary record was inadequate, and in the words of the judge the whole thing “is a complex and as of yet undecided question that is not suitable for determination by way of a summary judgment application.”

Nevertheless, the court made an order on this summary judgement application. Perhaps this illustrates how usefully flexible the law can be, when it wants to be. The court ordered “that Copytrack be entitled to trace and recover the 529.8273791 Ether Tokens received by Wall from Copytrack on 15 February 2018 in whatsoever hands those Ether Tokens may currently be held.”

How, exactly, this order will be enforced remains to be seen. It is likely that the resolution of this particular dispute will move out of the courts and into a private settlement, with the result that these issues will remain complex and undecided as far as the court is concerned. A few takeaways from this decision:

- As with all new technologies, the court requires support and, in some cases, expert evidence, to understand the technical background and place things in context. This case is no different, but the comments from the court suggest something was lacking here: “Nowhere in its submission did Copytrack address the question of whether cryptocurrency, including the Ether Tokens, are in fact goods or the question of if or how cryptocurrency could be subject to claims for conversion and wrongful detention.”

- It is interesting to note that blockchain-based currencies, such as the CPY and Ether tokens at issue in this case, are susceptible to claims of hacking. “The evidence of what has happened to the Ether Tokens since is somewhat murky”, the court notes dryly. This flies in the face of one of the central claims advanced by blockchain advocates: transactions are stored on an immutable open ledger that tracks every step in a traceable, transparent and irreversible record. If the records are open and immutable, how can there be any confusion about these transfers? How do we reconcile these two seemingly contradictory positions? The answer is somewhere in the ‘last mile’ between the ledgerized tokens (which sit on a blockchain), and the cryptocurrency exchanges and virtual wallets (using ‘non-blockchain’ user-interface software for the trading and management of various cryptocurrency accounts). It may be infeasible to hack blockchain ledgers, but it’s relatively feasible to hack the exchange or wallet. This remains a vulnerability in existing systems.

- Lastly, this decision is one of the first in Canada directly addressing the enforcement of rights to ownership of cryptocurrency. Clearly, the law in this area requires further development – even in answering the basic questions of whether cryptocurrency qualifies as an asset covered by the doctrines of conversion and detinue (answer: it probably does). This also illustrates the requirement for traditional dispute resolution mechanisms between international parties, even in disputes involving a smart-contract company such as Copytrack. The fine-print in agreements between industry players will remain important when resolving such disputes in the future.

Seek experienced counsel when confronting cryptocurrency issues, smart contracts and blockchain-based rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsA Software Vendor and its Customer: “like ships passing on a foggy nightâ€

By Richard Stobbe

When a customer got into a dispute with the software vendor about the license fees, the resulting case reads like a cautionary tale about software licensing. In ProPurchaser.com Inc. v. Wifidelity Inc., 2017 ONSC 7307 (CanLII), the court reviewed a dispute about a Software License Agreement. The customer, ProPurchaser, signed a license agreement with Wifidelity for the license of certain custom software at a rate of $6,000 per month. Over time, this fee increased and at the time the dispute commenced in 2017, ProPurchaser was paying a monthly fee of about $42,000.  The customer paid this fee, but apparently had no way of telling what it was paying for.

Detailed invoices were never submitted and so it was impossible to tell objectively how this fee should be broken down between license fees, support fees, expenses, or commissions.  The customer had formed the impression that this increase was due to support fees at an hourly rate, since the original license of $6,000 per month remained in effect and had never been amended in writing.

The software vendor, on the other hand, gave evidence that the license fee had increased under a verbal agreement between the parties.  “Based on the conflicting evidence,†the court mused, “it seems that the parties, much like ships passing on a foggy night, proceeded for several years unaware of the other’s different understanding about what was being charged by Wifidelity and paid for by ProPurchaser.â€

Under the Software License, either party was entitled to terminate without cause, by providing 14 days’ written notice to the other party. Eventually, the software vendor, Wifidelity, exercised the right of termination, triggering the lawsuit. ProPurchaser immediately sought a court order preserving the status quo, to prevent the software vendor from shutting down the software. In August, the court granted that order for a period of six months, subject to continuing payment of the $42,000 monthly license fee by ProPurchaser.  In November, ProPurchaser again approached the court, this time for an order extending the order until trial. Such an order could, in effect, be tantamount to a final resolution of the dispute, forcing the license to remain in effect. However, this would fly in the face of the clear terms of the agreement, which permitted for termination on 14 days’ notice.

While the dispute has yet to go to trial, there are some interesting lessons for software vendors and licensees:

- From a legal perspective, in order to succeed in its injunction application, ProPurchaser had to convince the court that termination of the license caused “irreparable harmâ€. However, the agreement itself allowed each party to terminate for no reason on very short notice, making it difficult to argue that this outcome – one that both sides had agreed to – would cause harm. If it caused so much harm, why did ProPurchaser agree to it in the first place? And in any event, any harm was compensable in damages and therefore not “irreparableâ€.

- That was a problem for the customer, when making a fairly narrow legal argument, but it’s also a problem from a business perspective. If the licensed software supports mission-critical functions within the licensee’s business, then make sure it’s not terminable for convenience by the software vendor.

- If changes are made to the software license agreement, particularly regarding the essential business terms like license fees and support fees, make sure these amendments are captured in writing, through a revised pricing schedule, or detailed invoicing that has been accepted by both sides.

Calgary – 13:00Â MST

No comments

Copyright in Seismic Data is Confirmed

By Richard Stobbe

In a decision last year, GSI (Geophysical Service Incorporated) sued to win control over seismic data that it claimed to own. GSI used copyright principles to argue that by creating databases of seismic data, it was the proper owner of the copyright in such data. GSI argued that Encana, by copying and using that data without the consent of GSI, was engaged in copyright infringement. That was the core of GSI’s argument in multi-party litigation, which GSI brought against Encana and about two dozen other industry players, including commercial copying companies and data resellers. The data, originally gathered and “authored” by GSI, was required to be disclosed to regulators under the regime which governs Canadian offshore petroleum resources. Seismic data is licensed to users under strict conditions, and for a fee. Copying the seismic data, by any method or in any form, is not permitted under these license agreements. However, it is customary for many in the industry to acquire copies of the data from the regulator, after the privilege period expired, and many took advantage of this method of accessing such data.

A lower court decision in April 2016 (see: Geophysical Service Incorporated v Encana Corporation, 2016 ABQB 230 (CanLII)) Â agreed with GSI that seismic data could be protected by copyright. However, the court rejected the copyright infringement claims, saying that the regulatory regime permits the regulator to make such materials available for anyone – including industry stakeholders – to view and copy. Thus, GSI’s central infringement claim was dismissed.

GSI appealed, and in April, 2017 the Alberta Court of Appeal (Geophysical Service Incorporated v EnCana Corporation, 2017 ABCA 125 (CanLII)) unanimously agreed to uphold the lower court decision and reject GSI’s appeal. The decision confirmed that industry players have a legal right to use and copy such data after expiry of the confidentiality period, and the court was clear that regulators have the “unfettered and unconditional legal right … to disseminate, in their sole discretion as they see fit, all materials acquired … and collected under the Regulatory Regimeâ€. While the regulatory regime in this case does not specify that seismic data may be “copiedâ€, there are extensive provisions about “disclosureâ€, none of which list any restrictions after expiry or the confidentiality or privilege period. Thus, the ability to copy data is the only rational interpretation which aligns with the objectives of the legislation.

This decision will apply not only to the specific area of seismic data, but to any materials which are released to the public pursuant to a similar regulatory regime.

Field Law acted for two of the successful respondents in the appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

IP Licenses & Bankruptcy (Part 2 – Seismic Data)

By Richard Stobbe

What happens to a license for seismic data when the licensee suffers a bankruptcy event?

In Part 1, we looked at a case of bankruptcy of the IP owner.

However, what about the case where the licensee is bankrupt? In the case of seismic, we’re talking about the bankruptcy of the company that is licensed to use the seismic data. Most seismic data agreements are licenses to use a certain dataset subject to certain restrictions. Remember, licences are simply contractual rights.  A trustee or receiver of a bankrupt licensee is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the trustee or receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts.

The only limitation is that a trustee cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, a seismic data license agreement does not grant a property right; it does not transfer a property interest in the data. It’s merely a contractual right to use. Bankruptcy trustees have the ability to disclaim these license agreements.

Can a trustee transfer the license to a new owner? If the seismic data license is not otherwise terminated on bankruptcy of the licensee, and depending on the assignment provisions within that license agreement, then it may be possible for the trustee to transfer the license to a new licensee. Transfer fees are often payable under the terms of the license. Assuming transfer is permitted, the transfer is not a transfer of ownership of the underlying dataset, but a transfer of the license agreement which grants a right to use that dataset.

The underlying seismic data is copyright-protected data that is owned by a particular owner. Even if a copy of that dataset is “sold” to a new owner in the course of a bankruptcy sale, it does not result in a transfer of ownership of the copyright in the seismic data, but rather merely a transfer of the license agreement to use that data subject to certain restrictions and conditions.

A purchaser who acquires a seismic data license as part of a bankruptcy sale is merely acquiring a limited right to use, not an unrestricted ownership interest in the data. The purchaser is stepping into the shoes of the bankrupt licensee and can only acquire the scope of rights enjoyed by the original licensee – neither more nor less. Any use of that data by the new licensee outside the scope of those rights would be a breach of the license agreement, and may constitute copyright infringement.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

No commentsIP Licenses & Bankruptcy Laws (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

When a company goes through bankruptcy, it’s a process that can up-end all of the company’s contractual relationships. When that bankrupt company is a licensor of intellectual property, then the license agreement can be one of the contracts that is impacted. A recent decision has clarified the rights of licensees in the context of bankruptcy.

In our earlier post – Changes to Canada’s Bankruptcy Laws – we reviewed changes to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) back in 2009. These changes have now been interpreted by the courts, some seven years later.

In Golden Opportunities Fund Inc. v Phenomenome Discoveries Inc., 2016 SKQB 306 (CanLII),  the court reviewed a license between a parent and its wholly-owned subsidiary. Through a license agreement, a startup licensor, which was the owner of a patent covering an invention pertaining to the testing and analysis of blood samples, licensed a patented invention to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Phenomenome Discoveries Inc. (PDI). PDI, in turn was the owner of any improvements that it developed in the patented invention, subject to a license of those improvements back to the parent company.

PDI went bankrupt. The parent company objected when the court-appointed receiver tried to sell the improvements to a new owner, free and clear of the obligations in the license agreement. In other words, the parent company wanted the right to continue its use of the licensed improvements and objected that the court-appointed receiver tried to sell those improvements without honoring the existing license agreement.

In particular, the parent company based its argument on those 2009 changes to Canada’s bankruptcy laws, arguing that licensees were now permitted keep using the licensed IP, even if the licensor went bankrupt, as long as the licensee continues to perform its obligations under the license agreement. Put another way, the changes in section 65.11 of the BIA should operate to prohibit a receiver from disclaiming or cancelling an agreement pertaining to intellectual property. The court disagreed.

The court clarified that “Section 65.11(7) of the BIA has no bearing on a court-appointed receivership.” Instead the decision in “Body Blue continues to apply to licences within the context of court-appointed receiverships. Licences are simply contractual rights.” (Note, the Body Blue case is discussed here.)

The court went on to note that a receiver is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts. The only limitation is that a receiver cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, IP license agreements do not grant a property right, but are merely a contractual right to use. Court-appointed receivers can disclaim these license agreements and can sell or dispose of the licensed IP free and clear of the license obligations, despite the language of Section 65.11(7) of the BIA.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

3 comments

Licensees Beware: assignment provisions in a license agreement

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say a company negotiates a patent license agreement with the patent owner. The agreement includes a clear prohibition against assignment – in other words, for either party to transfer their rights under the agreement, they have to get the consent of the other party. Â So what happens if the underlying patent is transferred by the patent owner?

The clause in a recent case was very clear:

Neither party hereto shall assign, subcontract, sublicense or otherwise transfer this Agreement or any interest hereunder, or assign or delegate any of its rights or obligations hereunder, without the prior written consent of the other party. Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect. This Agreement shall be binding upon, and shall inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective successors and heirs. [Emphasis added]

That was the clause appearing in a license agreement for a patented waterproof zipper between YKK Corp. and Au Haven LLC, the patent owner.  YKK negotiated an exclusive license to manufacture the patented zippers in exchange for a royalty on sales. Through a series of assignments, ownership of the patent was transferred to a new owner, Trelleborg. YKK, however, did not consent to the assignment of the patent to Trelleborg. The new owner later joined Au Haven and they both sued YKK for breach of the patent license agreement as well as infringement of the licensed patent.

YKK countered, arguing that Trelleborg (the patent owner) did not have standing to sue, since the purported assignment was void, according to the clause quoted above, due to the fact that YKK’s consent was never obtained: “Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect.” (Emphasis added) In other words, Â YKK argued that since the attempted assignment of the patent was done without consent, it was not an effective assignment, and thus Trelleborg was not the proper owner of the patent, and thus had no right to sue for infringement of that patent.

The court considered this in the recent US decision in Au New Haven LLC v. YKK Corporation (US District Court SDNY, Sept. 28, 2016) (hat tip to Finnegan). Rejecting YKK’s argument, the court found that the clause did not prevent assignments of the underlying patent or render assignments of the patent invalid, since the clause only prohibited assignments of the agreement and of any interest under the agreement, and it did not specifically mention the assignment of the patent itself.

Thus, the transfer of the patent (even though it was done without YKK’s consent) was valid, meaning Trelleborg had the right to sue for infringement of that patent.

Both licensors and licensees should take care to consider the consequences of the assignment provisions of their license, whether assignment is permitted by the licensee or licensor, and whether assignment of the underlying patent should be controlled under the agreement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsBozo’s Flippity-Flop and Shooting Stars: A cautionary tale about rights management

By Richard Stobbe

If you’ve ever taken piano lessons then titles like “Bozo’s Flippity-Flop”, “Shooting Stars” and “Little Elves and Pixies” may be familiar.

These are among the titles that were drawn into a recent copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the Royal Conservatory against a rival music publisher for publication of a series of musical works. In Royal Conservatory of Music v. Macintosh (Novus Via Music Group Inc.) 2016 FC 929, the Royal Conservatory and its publishing arm Frederick Harris Music sought damages for publication of these works by Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music.

The case serves as a cautionary tale about records and rights management, since much of the confusion between the parties, and indeed within the case itself, could be blamed on missing or incomplete records about who ultimately had the rights to the musical works at issue. In particular, a 1999 agreement which would have clarified the scope of rights, was completely missing. The court ultimately determined that there was no evidence that the defendants Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music could benefit from any rights to publish these songs; the missing 1999 agreement was never assigned or extended to the defendants.

In assessing damages for infringement, the court reviewed the factors set forth in the Copyright Act, including:

- Â the good faith or bad faith of the defendant;

- Â the conduct of the parties before and during the proceedings;

- Â the need to deter other infringements of the copyright in question;

- Â in the case of infringements for non-commercial purposes, the need for an award to be proportionate to the infringements, in consideration of the hardship the award may cause to the defendant, whether the infringement was for private purposes or not, and the impact of the infringements on the plaintiff.

In evaluating the deterrence factor, the court noted: “it is unclear what effect a large damages award would have in deterring further copyright infringement, when the infringement at issue here appears to be the product of poor record-keeping and rights management on the part of both parties.  If anything, this case is instructive that the failure to keep crucial contracts muddies the waters around rights, and any resulting infringement claims. The Respondents should not alone bear the brunt of this laxity, because the Applicants played an equal part in the inability to provide to the Court the key document at issue.” [Italics added]

For these reasons, the court set per work damages at the lowest end of the commercial range ($500 per work), for a total award of $10,500 in damages.

Calgary – o7:00 MST

No commentsCopyright and the Creative Commons License

By Richard Stobbe

There are dozens of online photo-sharing platforms. When using such photo-sharing venues, photographers should take care not to make the same mistake as Art Drauglis, who posted a photo to his online account through the photo-sharing site Flickr, and then discovered that it had been published on the cover of someone else’s book. Mr. Drauglis made his photo available through a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which permitted reproduction of his photo, even for commercial purposes.

You might be surprised to find out how much online content is licensed through the “Creative Commons†licensing regime. According to recent estimates, adoption of Creative Commons (CC) has expanded from 140 million licensed works in 2006, to over 1 billion today, including hundreds of millions of images and videos.

In the decision in Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group LLC (U.S. District Court D.C., cv-14-1043, Aug. 18, 2015), the federal court acknowledged that, under the terms of the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, the photo was licensed for commercial use, so long as proper attribution was given according to the technical requirements in the license. The court found that Kappa Map Group complied with the attribution requirements by listing the essential information on the back cover. The publisher’s use of the photo did not exceed the scope of the CC license; the copyright claim was dismissed.

There are several flavours of CC license:

- The Attribution License (known as CC BY)

- The Attribution-ShareAlike License (CC BY-SA)

- The Attribution-NoDerivs License (CC BY-ND)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial License (CC BY-NC)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (CC BY-NC-ND)

- Lastly, a so-called Public Domain (CC0) designation permits the owner of a work to make it available with “No Rights Reservedâ€, essentially waiving all copyright claims.

Looks confusing? Even within these categories, there are variations and iterations. For example, there is a version 1.0, all the way up to version 4.0 of each license. The licenses are also translated into multiple languages.

Remember: “available on the internet†is not the same as “free for the takingâ€. Get advice on the use of content which is made available under any Creative Commons license.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

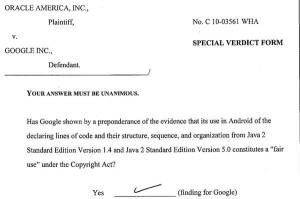

No commentsAndroid vs. Java: Copyright Update

By Richard Stobbe

In a sprawling,  billion-dollar lawsuit that started in 2010, a jury yesterday returned a verdict in favour of Google, delivering a blow to Oracle.  (For those who have lost the thread of this story, see : API Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round).

The essence of Oracle America Inc. v. Google Inc. is a claim by Oracle that Google’s Android operating system copied a number of APIs from Oracle’s Java code, and this copying constituted copyright infringement. Infringement, Oracle argued, that should give rise to damages based on Google’s use of Android. Now think for a minute of the profits that Google might attribute to its use of Android, which has dominated mobile operating system since its introduction in 2007. Oracle claimed damages of almost $10 billion.

In prior decisions, the US Federal Court decided that Google’s copying did infringe Oracle’s copyright. The central issue in this phase was whether Google could sustain a ‘fair use’ defense to that infringement. Yesterday, the jury sided with Google, deciding that Google’s use of the copied code constituted ‘fair use’, effectively quashing Oracle’s damages claim.

Oracle reportedly vowed to appeal.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsClickwrap Agreement From a Paper Contract?

By Richard Stobbe

Can a binding contract be formed merely with a link to another set of terms? (For background on this topic, check out our earlier post What, exactly, is a browsewrap? which reviews browsewraps, clickwraps, clickthroughs, terms of use, terms of service and EULAs).

The answer is clearly… it depends. Consider the American case of Holdbrook Pediatric Dental, LLC, v. Pro Computer Service, LLC (PCS), a New Jersey decision which considered the enforceability of a set of terms which were linked from a paper hard-copy version of the contract. In this case, PCS sent a contract to its customer electronically. The customer printed out the paper version and signed it in hard copy. A hyperlink appeared near the signature line, pointing to a separate set of Terms and Conditions in HTML code. Of course on the paper copy these terms cannot be hyperlinked.

PCS asserted that these separate terms were incorporated into the signed paper contract, since they function as a clickable hyperlink in the electronic version.  The court disagreed: “In order for there to be a proper and enforceable incorporation by reference of a separate document . . . the party to be bound by the terms must have had ‘knowledge of and assented to the incorporated terms.’”  Here, there was no independent assent to the additional Terms and Conditions, and the mixed media nature of the contracting process worked against PCS. In addition to the fact that the separate terms were not easily accessible by the customer, the text was not clear. It merely said “Download Terms and Conditions”, without providing reasonable notice to the customer that assent to the main contract included assent to these additional terms. The additional terms were not binding on the customer.

Lessons for business? Get legal advice!

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsFacebook Follows Google to the SCC

By Richard Stobbe

A class action case against Facebook (see our previous posts for more background) is heading to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The BC Court of Appeal in Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2015 BCCA 279 (CanLII)  had reviewed the question of whether the Facebook terms (which apply California law) should be enforced in Canada or whether they should give way to local B.C. law. The appeal court reversed the trail judge and decided that the Facebook’s forum selection clause should be enforced.

Facebook now joins Google, whose own internet jurisdiction is also going up to the Supreme Court of Canada this year.

These are two cases to watch.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 comment

CASL Enforcement (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As reviewed in Part 1, since July 1, 2014, Canada’s Anti-Spam Law (or CASL) has been in effect, and the software-related provisions have been in force since January 15, 2015.

In January, 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) executed a search warrant at business locations in Ontario in the course of an ongoing investigation relating to the installation of malicious software (malware) (See: CRTC executes warrant in malicious malware investigation). The allegations also involve alteration of transmission data (such as an email’s address, date, time, origin) contrary to CASL. This represents one of the first enforcement actions under the computer-program provisions of CASL.

The first publicized case came in December, 2015, when the CRTC announced that it took down a “command-and-control server” located in Toronto as part of a coordinated international effort, working together with Federal Bureau of Investigation, Europol, Interpol, and the RCMP. This is perhaps the closest the CRTC gets to international criminal drama. (See: CRTC serves its first-ever warrant under CASL in botnet takedown).

Given the proliferation of malware, two actions in the span of a year cannot be described as aggressive enforcement, but it is very likely that this represents the visible tip of the iceberg of ongoing investigations.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentCBC v. SODRAC: Supreme Court on Canadian Copyright

By Richard Stobbe

The CBC, like all television broadcasters, makes copies of various works – such as music and other content – in the course of preparing programs for broadcast. So-called “synchronization copies†are used to add musical works to a program. Then a “master copy†is made, when the music synchronization is complete. The master copy of the completed program is loaded for broadcast, and various internal copies are made of the master copy. These copies are called “broadcast‑incidental copiesâ€. In a nutshell, these are copies made in the process of production of a program, as distinct from the broadcast of the program.

In one of the more esoteric copyright topics to make it to the Supreme Court, the decision in Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. SODRAC 2003 Inc., 2015 SCC 57 (CanLII), examined whether these “broadcast‑incidental copies†require a separate license because they would constitute an infringement of copyright if made without consent of the copyright owner. Or, rather, are they caught within the standard broadcast license that CBC would have negotiated with rightsholders, such as SODRAC, and thus they wouldn’t require a separate license… Still with me?

The Court decided that “broadcast‑incidental copying” engages the reproduction right in Section 3 of the Copyright Act. These so-called “ephemeral copies” are not exempted by ss. 30.8 and 30.9 of the Act. The Court noted that “While balance between user and right‑holder interests and technological neutrality are central to Canadian copyright law, they cannot change the express terms of the Act.” Importantly, the Court also cautioned that “The principle of technological neutrality recognizes that, absent parliamentary intent to the contrary, the Act should not be interpreted or applied to favour or discriminate against any particular form of technology.”

In the end the decision was sent back down to the Copyright Board for reconsideration of valuation of the license in accordance with the principles of technological neutrality and the balance between balance between user and right‑holder interests.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsLimitations of Liability: Do they work in the Alberta Oilpatch?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s consider that contract you’re about to sign. Does it contain a limitation of liability? And if so, are those even enforceable? It’s been several years since we last wrote about limitations of liability and exclusion clauses (See: Limitations of Liability: Do they work?) and it’s time for another look.

A limitation of liability seeks to reduce or cap one party’s liability to a certain dollar amount – usually a nominal amount. An exclusion clause is a bit different – the exclusion clause seeks to preclude any contractual claim whatsoever.

To understand the current state of the law, we have to look at the decision in Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. British Columbia (Transportation and Highways), 2010 SCC 4 (CanLII), 315 D.L.R. (4th) 385, where the Supreme Court of Canada laid down a three-part framework. This test requires the court to determine:

(a) whether, as a matter of interpretation, the exclusion clause applies to the circumstances established in the evidence;

(b) if the exclusion clause applies, whether the clause was unconscionable and therefore invalid, at the time the contract was made; and

(c) if the clause is held to be valid under (b), whether the Court should nevertheless refuse to enforce the exclusion clause, because of an “overriding public policy, proof of which lies on the other party seeking to avoid enforcement of the clause, that outweighs the very strong public interest in the enforcement of contractsâ€.

We can illustrate this if we apply these concepts to a recent Alberta case. In this case, the court considered a limitation of liability in the context of a standard form industry contract, the terms of which were negotiated between the Canadian Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Anyone doing business in the Alberta oilpatch will have seen one of these agreements, or something similar.

The court describes this agreement as a bilateral no-fault contract, where one party takes responsibility for damage or loss of its own equipment, regardless of how that damage or loss was caused. Precision Drilling Canada Limited Partnership v Yangarra Resources Ltd., 2015 ABQB 433 (CanLII) dealt with a situation where one of Precision’s employees caused damage to Yangarra’s well. In the end Yangarra lost $300,000 worth of equipment down the well, which was abandoned. Add the cost of fishing operations to retrieve the lost equipment (about $720,000), and add the cost of drilling a relief well (about $2.5 million). All of this could be traced to the conduct of one of Precision’s employees – ouch.

Despite all of this, the court decided that the bilateral risk allocation (exclusion of liability) clauses in the contract between Yangarra and Precision applied to allocate these costs to Yangarra, regardless of who caused the losses. The court decided that enforcing this limitation of liability clause was neither unconscionable nor contrary to public policy. The clause was upheld, and Precision escaped liability.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsApple’s Liability for the Xcode Hack

.

By Richard Stobbe

I don’t think I’m going out on a limb by speculating that someone, somewhere is preparing a class-action suit based on the recently disclosed hack of Apple’s app ecosystem.

How did it happen? In a nutshell, hackers were able to infect a version of Apple’s Xcode software package for iOS app developers. A number of iOS developers – primarily in China, according to recent reports – downloaded this corrupted version of Xcode, then used it to compile their apps. This corrupted version was not the “official” Apple version; it was accessed from a third-party file-sharing site. Apps compiled with this version of Xcode were infected with malware known as XcodeGhost. These corrupted apps were uploaded and distributed through Apple’s Chinese App Store. In this way the XcodeGhost malware snuck past Apple’s own code review protocols and, through the wonder of app store downloads, it infected millions of iOS devices around the world.

The malware does a number of nasty things – including fishing for a user’s iCloud password.

This case provides a good case study for how risk is allocated in license agreements and terms of service. What do Apple’s terms say about this kind of thing? In Canada, the App Store Terms and Conditions govern a user’s contractual relationship with Apple for the use of the App Store. On the face of it, these terms disclaim liability for any “…LOSS, CORRUPTION, ATTACK, VIRUSES, INTERFERENCE, HACKING, OR OTHER SECURITY INTRUSION, AND APPLE CANADA DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY RELATING THERETO.”

Apple could be expected to argue that this clause deflects liability. And if Apple is found liable, then it would seek the cover of its limitation of liability clause. In the current version of the terms, Apple claims an overall limit of liability of $50. Let’s not forget that “hundreds of millions of users” are potentially affected.

As a preliminary step however, Apple would be expected to argue that the law of the State of California governs the contract, and Apple would be arguing that any remedy must be sought in a California court (see our post the other day: Forum Selection in Online Terms).

Will this limit of liability and forum-selection clause hold up to the scrutiny of Canadian courts if there is a claim against Apple?

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsForum Selection in Online Terms

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say you’re a Canadian company doing business with a US supplier – which law should govern the contract? ‘Forum selection’ and ‘governing law’ refer to the practice of choosing the applicable law and venue for resolving disputes in a contract.

Software vendors and cloud service providers often include these clauses in their standard-form contracts as a means of ensuring that they enjoy home-turf advantage in the event of disputes. This is very common in consumer-facing contracts, such as Facebook’s Terms of Service. That contract says: “e laws of the State of California will govern this Statement, as well as any claim that might arise between you and us, without regard to conflict of law provisions.”

In our earlier post (Two Privacy Class Actions: Facebook and Apple), we looked at a BC decision which reviewed the question of whether the Facebook terms (which apply California law) should be enforced in Canada or whether they should give way to local law. The lower court accepted that, on its face, the Terms of Service were valid, clear and enforceable and the lower court went on to decide that Facebook’s Forum Selection Clause should be set aside in this case, and the claim should proceed in a B.C. court.

Facebook appealed that decision: Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2015 BCCA 279 (CanLII), (See this link to the Court of Appeal decision). The appeal court reversed and decided that the Forum Selection Clause should be enforced.

Interestingly, the court said “As a matter of B.C. law, no state (including B.C.) may unilaterally arrogate exclusive adjudicative jurisdiction for itself by purporting to apply its jurisdictional rules extraterritorially.” (See the debate regarding the Google and Equustek decision for a different perspective on the extraterritorial reach of B.C. courts.)

The Douez decision was fundamentally a class-action breach of privacy claim, and that claim was stopped through the Forum Selection Clause.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

2 comments