Canadian Site-Blocking Decision

By Richard Stobbe

A streaming service known as “GoldTV” was in the business of rebroadcasting television programing through online broadcasting or streaming services to Canadian consumers. This had the effect of eating into the core business model of traditional Canadian broadcasters such as Bell Media and Rogers. Can a broadcast company fight back against this type of streaming service by seeking a site-blocking order?

Based on copyright infringement allegations, the broadcasters took GoldTV to court and obtained interim court orders. Despite the issuance of the interim and interlocutory injunctions directly against GoldTV, some of the offending services remained accessible, and the alleged infringement continued. Basically, GoldTV remained anonymous and (practically speaking) beyond the reach of the Canadian courts. Bell Media and Rogers then sought an order to compel Canadian ISPs to block access to GoldTV’s sites.

We know that, under Canadian law, non-party actors can be ordered by a Canadian court to take certain steps. In Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., 2017 SCC 34 (CanLII), the Supreme Court of Canada approved a court order that required Google to globally de-index the websites of a company in breach of several court orders. The Court affirmed that injunctions can be issued against someone who is not a party to the underlying litigation.

In this recent decision, Bell Media Inc. v. GoldTV.Biz, 2019 FC 1432 (CanLII),  the court confirmed that it can order ISPs, such as Bell Canada, Fido, Telus and Shaw, to block the offending GoldTV sites. Although there are obvious analogies to the Equustek case, the court in GoldTV indicated an order of this nature has not previously issued in Canada but has in other jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom. Equustek involved de-indexing from a search engine, whereas the GoldTV case involves site-blocking. The court issued the site-blocking order, with a 2-year sunset clause.

Teksavvy Solutions (one of the ISPs bound by the order) has appealed this decision to the Federal Court of Appeal (PDF).

Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright Fight: Hollywood versus a Film School Project

By Richard Stobbe

In 2015 Pixar, Disney’s animation company, released INSIDE OUT, a feature-length animated film featuring a character whose emotions of Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust take the form of personified characters.  Did Pixar’s 2015 production infringe the copyright in the film school project from fifteen years earlier? That’s what Mr. Pourshian alleges, claiming that he is the owner of copyright in his original screenplay, live theatrical production, and short film, each of which are titled “Inside Out“, and that Pixar infringed those copyrights “by production, reproduction, distribution and communication to the public by telecommunication of the film INSIDE OUTâ€.

This case is more akin to Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73 (CanLII), where the infringement claim did not involve direct cut-and-paste copying, but rather was based on an assessment of the cumulative effect of the features copied from the original work, to determine whether those features amount to a substantial part of the skill and judgment of the original author, expressed in the original work as a whole. This involves a review of whether there is substantial copying of elements like particular visual elements of setting and character, content, theme and pace. Compare this one with Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc. (Anne with a © : Copyright infringement and the setting of a Netflix series).

The Pourshian case was a preliminary motion about whether the claim can proceed in Canada, or whether it should be heard in the US. The Court found that there was a real and substantial connection in relation to the claims and Ontario, and the case will be permitted to continue against Pixar Animation Studios, Walt Disney Pictures Inc. and Disney Shopping Inc.

If this case proceeds to trial, it will be fascinating to watch.

Mr. Pourshian did pursue a separate claim in California (Pourshian v. Disney, Case No. 5:18-cv-3624), which was voluntarily withdrawn in 2018.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright and Code: Can a Software Developer Take a Shortcut?

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say an employee is hired as a software engineer to develop an application for the employer.  The employee completes the project, and the software program is launched as a commercial product. Copyright is registered in the software, showing the employee as author, and the employer as owner. So far so good.

The employee leaves, and her company launches its own software product, which seems to compete directly with the software that was created for her former employer. Ok, now we have a problem.

Or do we? These are the basic facts in the interesting case of Knowmadics v. Cinnamon and LDX Inc., 2019 ONSC 6549 (CanLII), where an ex-employee left her employment in 2017, and within two months of signing a Non-Disclosure Agreement, her company LDX was offering software products that seemed to contain similar features and competed directly with Knowmadics, the former employer.

Knowmadics sued its former employee, claiming that the LDX software infringed the copyright of Knowmadics. The claim also alleged breach of the Employment Agreement, a Subcontractor Agreement, and a Non-Disclosure Agreement.

An analysis of the code showed that there were similarities and overlap between the software written for Knowmadics, the former employer, and the software sold by Ms. Cinnamon, the former employee through her company LDX.  However, Ms. Cinnamon raised a defence that makes perfect sense in light of the way that many software projects evolve: any similarities, the employee argued, were due to the simple fact that she used her own prior code in developing the program for Knowmadics, during her employment, and that same code was incorporated into a database that she wrote for an earlier client, and the same code was subsequently incorporated into the software she wrote for her own company, LDX. So of course it has similar features, it’s all from the code originally authored by the same developer.

To borrow from the court’s analysis: “The relevant issue as far as the database goes is a legal one for the Court to determine at trial: once Ms. Cinnamon delivered SilverEye to Knowmadics incorporating that prior database without identifying that she was doing so, and Knowmadics copyrighted SilverEye with that database code and schema, was Ms. Cinnamon then permitted under copyright law or her agreements with Knowmadics to take a shortcut and use the same code and schema to create a competing software with the same functionalities? This is a serious issue to be determined at trial…”

The reported decision dealt with a pre-trial injunction application. The order granted by the court simply maintained the status quo pending trial, so the merits of this case are still to be decided. If it does proceed to trial, this case will engage some very interesting issues around copyright, software, originality and licensing of code.

Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsThe Scope of Crown Copyright

By Richard Stobbe

It’s time to update our 2015 post about copyright in survey plans!  In the course of their work, land surveyors in Ontario prepare a survey document, and that document is routinely scanned into the province’s land registry database. Copies of survey documents can be ordered from the registry for a fee.

Land surveyors commenced a copyright class action lawsuit against Teranet Inc., the manager of the land registry system in Ontario.  The case travelled all the way up to Canada’s top court and in Keatley Surveying Ltd. v. Teranet Inc.  2019 SCC 43 the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) rendered a decision on the appeal: Copyright in plans of survey registered or deposited in the land registry office belongs to the Province of Ontario under s. 12 of the Copyright Act.

Section 12 of the Copyright Act provides a statutory basis for Crown copyright.

Under this section, the Crown holds copyright in any work “prepared or published by or under the direction or control of Her Majestyâ€.

The court aimed to balance the rights of the Crown in works that are prepared or published under the control of the Crown, where it’s necessary to guarantee the authenticity, accuracy and integrity of the works. However, the scope of Crown copyright should not expropriate the copyright of creators and authors.

Basically, Crown copyright applies where:

- The work is prepared by a Crown employee in the course of his or her employment or

- The Crown determines whether and how a work will be made, even if the work is produced by an independent contractor.

In both situations, the Crown exercises “direction and control†for the purposes of Section 12 of the Act.

In the Teranet case, the main question was whether the registered and deposited survey plans were published by or under the “direction or control†of the Crown. The court concluded that “When either the Crown or Teranet publishes the registered or deposited plans of survey, copyright vests in the Crown because the Crown exercises direction or control over the publication process.â€

Applying the principle of technological neutrality, the court indicated that the province’s use of new technologies (after digitization of the survey plans and publication process) did not change the court’s assessment of whether the Crown has copyright by virtue of s. 12. Finally, because the Crown owns copyright in the survey plans pursuant to s. 12 of the Act, there could be no infringement under the electronic registry system, and the class action was dismissed.

Background Reading:

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAnne with a © : Copyright infringement and the setting of a Netflix series

By Richard Stobbe

Is there copyright in the setting of a Netflix series?

It’s time for a dose of stereotypical Canadian culture, and you can’t do much better than another copyright battle over Anne of Green Gables! With Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc., 2019 ONSC 9 (CanLII) we can add to the  long list of cases surrounding the fictional character Anne. This newest case deals with a copyright claim by Sullivan Entertainment against the producers of a CBC / Netflix version entitled “ANNE with an E†(2017).

First, a newsflash: The Anne of Green Gables books were written by Lucy Maud Montgomery and originally published beginning in 1908.

Sullivan, of course, is known as the producer of a popular television version of the Anne of Green Gables novels, starting with “Anne of Green Gables†(1985), the copyright in which is registered under Canadian Copyright Registration No. 358612.

Enter the latest incarnation of the AGG story, a CBC series produced by Northwood Media, now streaming on Netflix.

Sullivan alleges that Northwood, the producer of the latest Netflix version, has copied certain elements that were created by Sullivan in its TV series from the 1980s, elements that were not in the original novels. This copyright claim forces an examination of the scope or range of copying that is permitted around setting, plot concepts, imagery, and production or design elements.

Wait… are plot concepts and settings even protectable? In copyright law, we know that ideas are not, on their own, protectable; copyright protects the expression of ideas. Here, Sullivan as the owner of the copyright in its television production alleges that the Netflix series infringes copyright by copying scenes, not literally but through non-literal copying of a substantial part of the original protected work.

For example, Sullivan alleges that the Netflix version copies settings or conceptual elements such as:

- the decision to set the story in the late 1890s (the choice made in the Sullivan version), as opposed to the 1870s (the choice made by the original author in the Anne of Green Gables novel).

- the use of steam trains, replicated from a scene in one of the Sullivan episodes (apparently steam trains would not have been historically accurate in a 1870s setting);

- copying the concept and scene of a class spelling bee, to establish the rivalry between Anne Shirley and Gilbert Blythe;

- depictions and staging of scenes such as Anne’s life with the Hammond family or Matthew Cuthbert passing by the hose of Mrs. Lynde’s on his way to the train station to pick up Anne.

The allegations are not that the scenes are literally cut-and-paste from the original, but that the copying of settings, concepts and staging is copying of “a substantial part” of the original for the purposes of establishing copyright infringement.

In the words of the court in Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73, copyright can protect “a feature or combination of features of the work, abstracted from it rather than forming a discrete part…. [T]he original elements in the plot of a play or novel may be a substantial part, so that copyright may be infringed by a work which does not reproduce a single sentence of the original.â€

(See our earlier article: Â Supreme Court on Copyright Infringement & Protection of Ideas )

The preliminary decision in Sullivan v. Northwood Media Inc. is about a pre-trial procedure related to document discovery, and once it goes to trial, the outcome will be interesting to see. This case is a series worth watching.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsCopyright, Obituaries, and $10 million in Statutory Damages

By Richard Stobbe

An obituary aggregation site – yes, there is such a thing – was in the business of reposting obituaries, both text and photos, taken from the sites of Canadian funeral homes and newspapers. This database of obituaries was a way to attract visitors who could then buy flowers and ‘virtual candles’ on the same page as the obituary, to generate profits.

Not surprisingly, someone complained.

Thomson v. Afterlife Network Inc., 2019 FC 545 (CanLII)Â was a class action lawsuit against the obituary aggregation company, Afterlife, for copyright infringement, based on the unauthorized copying and publication of over a million obituaries. Shortly after the class action lawsuit was launched, the Afterlife site shut itself down.

Class action members expressed that “an obituary they had written for a family member, often accompanied by a photograph, had been posted on Afterlife’s website without their permission. The evidence of many Class Members is that they had written the obituaries in a personal way and that their discovery that the obituaries had been reproduced with the addition of sales of candles and other advertising was an emotional blow to them. In some cases, inconsistent information was added, for example, inaccurate details about the deceased or options to order flowers where the family had specifically discouraged flowers. The Class Members also describe Afterlife’s conduct, in seeking to profit from their bereavement and in conveying to the public that the families were benefiting from sales of virtual candles or other advertising, as reprehensible, outrageous and exploitative.â€

The court had no trouble in establishing copyright protection for the obituaries as well as the photos.

The court also quickly concluded that Afterlife has republished this content without the permission of the original authors.

Damages need not be proven where statutory damages are invoked. Since statutory damages (Section 38.1 of the Copyright Act) allow for not less than $500 and not more than $20,000 per infringement, the court saw that the minimum of $500 multiplied by the estimated two million separate infringements (at least one photo plus a block of text in each of the 1 million copied obituaries), would result in a minimum damage award of around $1 billion.  Seeing this as grossly disproportionate, the court awarded $10 million in statutory damages, and another $10 million in aggravated damages, which can be awarded for compensatory purposes. Strangely, the court did not award punitive damages for this case of “obituary piracyâ€, that the court agreed was high-handed, reprehensible and “represents a marked departure from standards of decencyâ€.

Although this case may be noted for its significant statutory damage award, it also deal with a moral rights claim by the original authors of the obituaries. Under Canadian copyright law, “moral rights†protect the integrity of a work and are engaged where the author’s honour or reputation is prejudiced by the distortion or modification of the original work, or by using the work in association with a product, service, cause or institution.

The court struggled to find a moral rights infringement, since it was given evidence of the subjective elements of the infringement (the authors expressed that they were understandably mortified that others would think that they were somehow profiting from bereavement). However, the court noted that there is both a subjective and objective aspect in order to establish infringement of moral rights. The objective element was missing here.

In the end, a $20 million damage award was granted against Afterlife.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsCraft Beer Trademarks: The Ol’ Cease & Desist

By Richard Stobbe

Local Alberta breweries Elite Brewing (visited, love the carbon fibre bar) and Bow River Brewing have been on the receiving end of a cease and desist letter from the City of Calgary over a beer label for Fort Calgary ISA (a “richly hopped lighter bodied India session ale”).

The complaint by the City related to the unauthorized use of “FORT CALGARY”, which is an official mark owned by the City.

But wait, isn’t “FORT CALGARY” also an historical landmark and a place name?

From reading our other articles on geographical locations as trademarks, you might wonder how this works. You might say “Hang on… if a trademark is based on a geographic name, and a trademarks examiner decides that the geographic name is the same as the actual place of origin of the products, won’t the trademark be considered ‘clearly descriptive’ and thus unregistrable as a trademark? Furthermore, if the geographic name is NOT the same as the actual place of origin of the goods and services, the trademark will be considered ‘deceptively misdescriptive’ since the ordinary consumer would be misled into the belief that the products originated from the location of that geographic name. If that’s true, then how can a trademark owner assert rights over a geographic location?”

Yes, yes, that’s all true, with some exceptions, but according to Canadian trademark law there is also something called an official mark, which is what the City of Calgary owns. This is a rare species of super-mark that effectively sidesteps all of those petty concerns regarding geographical locations, ‘clearly descriptive’ and ‘deceptively misdescriptive’.

By virtue of its status as a government entity, the City can assert rights in certain marks that it adopts under Section 9 of the Trademarks Act.  These rights form the legal basis for the City’s recent cease and desist letter regarding the FORT CALGARY beer label.

This case has some unique elements due to the special rights that the City claims under the Trademarks Act, but the general message is the same: craft brewers can benefit from some preliminary trademark clearance searching when they launch a brand or a new beer name. And they should seek advice if they’re on the receiving end of this kind of letter.

In the end, the brewers reportedly agreed to sell out their remaining stock and refrain from further use of the Fort Calgary label, and the City agreed not to commence a lawsuit.

Need advice on beer trademarks and clearance searching? Contact craftlawyers.ca.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

No commentsMeeting Mike Tyson does not constitute consideration for Canadian copyright assignment

By Richard Stobbe

When is a contract really a contract and when is it just a type of unenforceable promise that can be revoked or cancelled?

Glasz c. Choko, 2018 QCCS 5020 (CanLII) is a case about ownership of raw documentary footage of Mike Tyson, the well-known boxer, and whether an email exchange was enough to form a binding contract between a promoter and a filmmaker.

The idea of “consideration” is supposed to be one of the important elements of an enforceable contract. There must be something of value exchanging hands between two parties as part of a contract. But that “something of value” can take many forms. The old English cases talk about a mere peppercorn as sufficient consideration.

In this case, a boxing the promoter, Mr. Choko, promised a pair of filmmakers that he had a special relationship with Mike Tyson, and could give them special access to obtain behind-the-scenes footage of Mr. Tyson during his visit to Toronto in 2014. An email was exchanged on September 4, 2014, in which the filmmakers agreed that, in exchange for gaining this access, the copyright in the footage would be owned by the promoter, Mr. Choko.

The filmmakers later revoked their assignment.

The parties sued each other for ownership of the footage. Let’s unpack this dispute: the footage is an original cinematographic work within the meaning of section 2 of the Copyright Act. The issues are: Was the work produced in the course of employment? If not, was the copyright ownership to the footage assigned to Mr. Choko by virtue of the Sept. 4th email? And were the filmmakers entitled to cancel or revoke that assignment?

There was no employment relationship, that much was clear. And the filmmaker argued that the agreement was not an enforceable contract since there was a failure of consideration, and that the promoter misrepresented the facts when he insisted on owning the footage personally. In fact, he misrepresented how well he really knew the Tyson family, and mislead the filmmakers when he said that Mrs. Tyson has specifically requested that the promoter should be the owner of the footage. She made no such request.

The promoter, Mr. Choko, argued that these filmmakers would never had the chance to meet Mike Tyson without his introduction: thus, the experience of meeting Mr. Tyson should be enough to meet the requirement for “consideration†in exchange for the assignment of copyright. However, the court was not convinced: “every creative work can arguably be said to involve an experience…” If we accepted an “experience” as sufficient consideration then there would never be a need to remunerate the author for the assignment of copyright in his or her work, since there would always be an experience of some kind.

Take note: Meeting Mr. Tyson was insufficient consideration for the purposes of an assignment Canadian copyright law.

For advice on copyright issues, whether or not involving Mr. Tyson, please contact Richard Stobbe.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsWho owns copyright in something that’s part of the law? (Fair Dealing and Crown Copyright)

By Richard Stobbe

A certain code is adopted into law. Someone sells copies of that code, but they’re sued for copyright infringement. So… who owns the copyright? If the government owns copyright, then how can a reproduction of the law be considered infringement?  If the government does not own copyright, then how did the code become part of the law in the first place?

These are the vexing questions that the Federal Court of Appeal tackled in a new and interesting decision on Crown copyright and fair dealing.

In P.S. Knight Co. Ltd. v. Canadian Standards Association, 2018 FCA 222, the court reviewed  copyright issues surrounding the Canadian Electrical Code, which has been adopted by federal and provincial legislation: for example, in Alberta, the Electrical Code Regulation formally declares the Canadian Electrical Code, Part 1 (Twenty‑third edition) to be “in force” in the province in respect of electrical systems. This means that the Code is essentially part of the law of the land, and there are penalties for any failure to comply. In fact, Alberta, Newfoundland, Ontario and Yukon expressly require that the Canadian Electrical Code be made available to the public in some form.

This is a commercial dispute that stretches back to the late 1960s, when Knight began developing products that competed with the publications of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA). Knight even created a simplified version of the Code (the Electrical Code Simplified). Through a series of events, Knight eventually sought to reproduce and sell the entire Canadian Electrical Code as its own publication, at a discount, undercutting the CSA price.  That’s when the CSA sued for copyright infringement. The CSA obtained an order for Knight to deliver up all infringing copies of the Code, Part I (the CSA Electrical Code or the Code), and ordered Knight Co. to pay statutory damages and costs of close to $100,000.

Knight appealed.

The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed Knight’s appeal, deciding that the Code is protected by copyright, even though it was developed and authored by committee. Just because the CSA made the Code available to be part of the mandated standard for the country, this doesn‘t mean the CSA gave up its own copyright interests in the Code.  The court also found that the Crown did not own copyright in the Code. As for the defence of ‘fair dealing’, the court weighed the various factors – the purpose of the dealing, character of the dealing, amount of the dealing, alternatives to the dealing, nature of the work and the effect of the dealing. It the court’s analysis, these factors “overwhelmingly“ supported the conclusion that Knight’s copying and sale of the Code did not qualify as “fair dealing.â€

In a strong dissent, Justice Webb seemed to appreciate the absurdity of penalizing someone from reproducing a Canadian law.

“What is in issue in this case,†according to the dissent, “is the right to publish certain works that have become part of the laws of Canada. …. Since the Code was considered as part of the text of the Regulations when it was incorporated by reference, it is the same as if it had been reproduced in full in the Regulations and, therefore, is part of the Regulations. Since the Reproduction of Federal Law Order permits any person to copy any enactment, the Crown has already granted P.S. Knight Co. Ltd. the right to copy the Code.â€

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

LEGO vs. LEPIN: Battle of the Brick Makers!

By Richard Stobbe

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

In any counterfeit battle involving the LEGO brand, we could have riffed off the successful line of LEGO Star Wars sets and made reference to the Attack of the Clones. But that’s been done, and anyway the recent legal battle between LEGO Group and a Chinese knock-off cut across more than just the Star Wars line: Shantou Meizhi Model Co., Ltd. essentially replicated the whole line of LEGO-brand products, including the popular Star Wars sets, licensed from Disney, the Friends line, the City, Technic and Creator product lines, as well as sets based on licensed movie franchises, like the Harry Potter and Batman lines. Lepin even sells a knock-off replica of the LEGO replica of the VW Camper Van, which sells under the “Lepin” brand for USD$48.00 (the Lego version sells for US$120).

The LEGO Group recently announced a win in Guangzhou Yuexiu District Court in China, based on unfair competition and infringement of its intellectual property rights in 3-dimensional artworks of 18 LEGO sets, and a number of LEGO Minifigures. This resulted in an injunction prohibiting the production, sale or promotion of the infringing sets, and a damage award of RMB 4.5 million.

While this decision is hailed as a win for LEGO, and a blow in favour of IP rights enforcement in China, the commercial reality is that 18 sets is a drop in the proverbial ocean of counterfeits for LEGO. A quick spin around the Lepin website shows that there is a sprawling product line available to the marketplace, most of which are direct copies of the corresponding LEGO sets. These are copies in appearance at least, since the quality of the Lepin product is … different, when compared to the quality of LEGO branded merchandise, according to some online reviews.

The connectable plastic brick which was popularized by LEGO is not, in itself, protectable from the IP perspective (patents expired long ago, and the trademarks in the brick shape were struck down in Canada). This permits entry by competitors such as MEGA-BLOKS, a company that sells a virtually identical interlocking brick, but under a distinctive brand, with original set designs, and rival licensing deals of its own Рfeaturing the likes of Pok̩mon, Sesame Street, John Deere and Star Trek.

While the bricks are just bricks, the LEGO trademarks are protectable, and as LEGO established, so are the rights in three-dimensional set designs, packaging art and other elements that were shamelessly copied by the busy folks at Lepin.

Protection of market share is a complex undertaking, where an intellectual property strategy is one element.  Looking for advice on how to protect your business using IP as a tool? Contact our IP advisors to start the conversation.

Related Reading: Battle of the Blocks (looking at the battle between Lego and Mega Blocks in Canada).

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Cryptocurrency Decision: Enforcing Blockchain Rights

.

By Richard Stobbe

A seemingly simple dispute lands on the desk of a judge in Vancouver, BC. By analogy, it could be described like this:

- AÂ Canadian purchased 530 units of foreign currency #1 from a Singapore-based currency trader.

- By mistake, the currency trader transferred 530 units of currency #2 to the account of the Canadian.

- It turns out that 530 units of currency #1 are worth $780.

- You guessed it, 530 units of currency #2 are worth $495,000.

- Whoops.

- The Singaporean currency trader immediately contacts the Canadian and asks that the currency be returned, to correct the mistake.

Seems simple, right? The Canadian is only entitled to keep the currency worth $780, and he should be ordered to return the balance.

Now, let’s complicate matters somewhat. The recent decision in Copytrack Pte Ltd. v Wall, 2018 BCSC 1709 (CanLII), one of the early decisions dealing directly with blockchain rights, addresses this scenario but with a few twists:

Copytrack is a Singapore-based company which has established a service to allow copyright owners, such as photographers, to enforce their copyrights internationally. Copyright owners do this by registering their images with Copytrack, and then deploying software to detect instances of online infringement. When infringement is detected, the copyright owner extracts a payment from the infringer, and Copytrack earns a fee. This copyright enforcement business is not new. However, riding the wave of interest in blockchain and smart contracts, Copytrack has launched a new blockchain-based copyright registry coupled with a set of cryptocurrency tokens, to permit the tracking of copyrights using a blockchain ledger, and payments using blockchain-based cryptocurrency.  Therefore, instead of traditional fiat currency, like US dollars and Euros, which is underpinned by a highly regulated international financial services industry, this case involves different cryptocurrency tokens.

When Copytrack started selling CPY tokens to support their new system, a Canadian, Mr. Wall, subscribed for 580 CPY tokens at a price of about $780. Copytrack transferred 580 Ether tokens to his online wallet by mistake, enriching the account with almost half a million dollars worth of cryptocurrency. Mr. Wall essentially argued that someone hacked into his account and transferred those 530 Ether tokens out of his virtual wallet. Since he lacked control over those units of cryptocurrency, he was unable to return them to Copytrack.

The argument by Copytrack was based in an old legal principle of conversion – this is the idea that an owner has certain rights in a situation where goods (including funds) are wrongfully disposed of, which has the effect of denying the rightful owner of the benefit of those goods. With a stretch, the court seemed prepared to apply this legal principle to intangible cryptocurrency tokens, even though the issue was not really argued, legal research was apparently not presented, the proper characterization of cryptocurrency tokens was unclear to the court, the evidentiary record was inadequate, and in the words of the judge the whole thing “is a complex and as of yet undecided question that is not suitable for determination by way of a summary judgment application.”

Nevertheless, the court made an order on this summary judgement application. Perhaps this illustrates how usefully flexible the law can be, when it wants to be. The court ordered “that Copytrack be entitled to trace and recover the 529.8273791 Ether Tokens received by Wall from Copytrack on 15 February 2018 in whatsoever hands those Ether Tokens may currently be held.”

How, exactly, this order will be enforced remains to be seen. It is likely that the resolution of this particular dispute will move out of the courts and into a private settlement, with the result that these issues will remain complex and undecided as far as the court is concerned. A few takeaways from this decision:

- As with all new technologies, the court requires support and, in some cases, expert evidence, to understand the technical background and place things in context. This case is no different, but the comments from the court suggest something was lacking here: “Nowhere in its submission did Copytrack address the question of whether cryptocurrency, including the Ether Tokens, are in fact goods or the question of if or how cryptocurrency could be subject to claims for conversion and wrongful detention.”

- It is interesting to note that blockchain-based currencies, such as the CPY and Ether tokens at issue in this case, are susceptible to claims of hacking. “The evidence of what has happened to the Ether Tokens since is somewhat murky”, the court notes dryly. This flies in the face of one of the central claims advanced by blockchain advocates: transactions are stored on an immutable open ledger that tracks every step in a traceable, transparent and irreversible record. If the records are open and immutable, how can there be any confusion about these transfers? How do we reconcile these two seemingly contradictory positions? The answer is somewhere in the ‘last mile’ between the ledgerized tokens (which sit on a blockchain), and the cryptocurrency exchanges and virtual wallets (using ‘non-blockchain’ user-interface software for the trading and management of various cryptocurrency accounts). It may be infeasible to hack blockchain ledgers, but it’s relatively feasible to hack the exchange or wallet. This remains a vulnerability in existing systems.

- Lastly, this decision is one of the first in Canada directly addressing the enforcement of rights to ownership of cryptocurrency. Clearly, the law in this area requires further development – even in answering the basic questions of whether cryptocurrency qualifies as an asset covered by the doctrines of conversion and detinue (answer: it probably does). This also illustrates the requirement for traditional dispute resolution mechanisms between international parties, even in disputes involving a smart-contract company such as Copytrack. The fine-print in agreements between industry players will remain important when resolving such disputes in the future.

Seek experienced counsel when confronting cryptocurrency issues, smart contracts and blockchain-based rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments#Illegal #Infringement : Defamation & Social Media

.

By Richard Stobbe

Can a hashtag constitute defamation?

In an Ontario case involving a music collaboration gone wrong, the answer apparently is yes. The dispute involved Mr. Johnson, who was allegedly a songwriter and music producer. Ms. Rakhmanova was also a song writer and signer. The two musicians collaborated on several tracks which were later the subject of a bitter dispute.

According to the judgement, Mr. Johnson released the tracks online, over the objections of Ms. Rakhmanova. At one point, after the songs were mixed and mastered, Ms. Rakhmanova requested that Mr. Johnson sign a recording contract, to memorialize the joint-authorship and ownership of the tracks, including equal publishing credit. Mr. Johnson refused to sign the contract since, according to the judgement, he intended to claim sole ownership over the three songs. Ms. Rakhmanova withdrew her consent to the release of her melodies and vocal tracks.  By then, however, the track had already been released online. Mr. Johnson failed to properly account for any revenue or royalties, and did not include proper attribution of Ms. Rakhmanova’s contributions: her picture and name were omitted from certain track names.

Ms. Rakhmanova then launched a series of online communications – through emails, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram accounts and SoundCloud posts – demanding removal of the content, and generally calling out Mr. Johnson for his conduct that, in her view, could be described as “…#stealing“, “infringing of my copyright“, “#piracy” “#plagiarism“, “#Infringement“, “#Illegal“, and characterizing Mr. Johnson as akin to “con artists who shamelessly peddle stolen acappellas“…

In Johnson v. Rakhmanova, 2018 ONSC 5258 (CanLII), the Court reviewed a defamation claim by Mr. Johnson, based on comments of this type. Interestingly, the Court flagged the defamatory elements in the various extracts, specifically highlighting certain hashtags such as “#piracy” “#plagiarism”, “#Infringement”, “#Illegal”. While none of the social media posts consisted of only hashtags (there was always more content included in the post), it is worth noting that, for certain posts, the judge highlighted the hashtag alone as constituting the only defamatory element. This suggests that, in the right context, a well-placed hashtag can constitute a defamatory statement.

A finding of defamation raises a presumption that the words complained of were false, that they were communicated with malice and that the plaintiff suffered damage.  That presumption of falsity is rebutted by the defendant proving truth or justification.  In the end, the Court took the view that most of these defamatory statements were accurate and truthful and therefore justified. And therefore not defamatory. The court dismissed Mr. Johnson’s defamation claim in any event, and awarded costs to Ms. Rakhmanova.

Calgary -7:00 MST

No commentsEnforcing Rights Online: Copyright Infringement & “Norwich Orders”

.

By Richard Stobbe

When a copyright owner seeks to enforce against online copyright infringement, it often faces a problem: who is engaging in the infringing activity?  If the old adage holds true – on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog – then the corollary is that there must be a lot of canines engaged in online copyright infringement.

Of course a copyright owner can only enforce its rights against online infringement if it knows the identity of the infringer.  The Canadian solution, which is enshrined in the Copyright Act,  is the so-called “notice-and-notice” regime, which allows a copyright holder to send a notice to the ISP (internet service provider), and the ISP is obliged by the Copyright Act to send that notice to the alleged infringer, who still remains anonymous.  The notice of infringement is passed along… but the infringing content remains online.  Since the “notice-and-notice” regime is not much of an enforcement tool, the path eventually leads copyright holders to seek a court order (called a Norwich order) to disclose the identity of those alleged infringers.  (See our previous articles about Norwich Orders for background.)

In Rogers Communications Inc. v. Voltage Pictures, LLC, 2018 SCC 38, a film production company (Voltage) alleged copyright infringement by certain anonymous internet users. Allegedly, films were being shared using peer-to-peer file sharing networks. Yes, apparently peer-to-peer file sharing networks are still a thing. Voltage sued one anonymous alleged infringer and brought a motion for a Norwich order to compel the ISP (Rogers) to disclose the identity of the infringer.

Now we get to a practical problem: who pays for the disclosure of these records?

Pointing to sections 41.25 and 41.26 of the Copyright Act, Voltage argued that the disclosure order be made without anything payable to Rogers. In essence, Voltage argued that the “notice and notice†regime does two things: it creates a statutory obligation to forward the notice of claimed infringement to the anonymous infringer. The Act also prohibit ISPs from charging a fee for complying with these “notice-and-notice” obligations. In response, Rogers argued that there is a distinction between sending the notice to the anonymous infringer (for which it cannot charge a fee) and disclosing the identity of that (alleged) infringer pursuant to a Norwich order. The Act does not specify that ISPs are prohibited from charging a fee for this step.

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) agreed that there is a distinction to be made: on the one hand, an ISP has obligations under the Copyright Act to ensure the accuracy of its records for the purposes of the notice and notice regime, and on the other hand, an ISP may be obliged, under a Norwich order to actually identify a person from its records. In a nutshell, the court reasoned that ISPs must retain records under the Act, in a form and manner that permits an ISP to identify the name and address of the person to whom notice is forwarded for the “notice-and-notice” purposes. But the Act does not require that these records be kept in a form and manner which would permit a copyright owner or a court to identify that person.  The copyright owner would only be entitled to receive that kind of information from an ISP under the terms of a Norwich order. The Norwich order is a process that falls outside the ISP’s obligations under the notice and notice regime. In the end, an ISP can recover its costs of compliance with a Norwich order, but ISPs cannot be compensated for every cost that it incurs in complying with such an order:

“Recoverable costs must be reasonable and must arise from compliance with the Norwich order. Where costs should have been borne by an ISP in performing its statutory obligations under the notice and notice regime, these costs cannot be characterized as either reasonable or as arising from compliance with a Norwich order, and cannot be recovered.”

According to Rogers, there are eight steps in its process to disclose the identity of one of its subscribers in response to a Norwich order.  The SCC made reference to this eight-step process, but wasn’t in a position to decide which of these steps overlap with Rogers’ obligations under the Act (for which Rogers was not entitled to reimbursement) and the steps which are “reasonable costs of compliance” (for which Rogers was entitled to reimbursement). The question was returned to the lower court for determination.

For copyright owners, its clear that ISPs will not shoulder the entire cost of disclosing the identity of subscribers at the Norwich stage. How much of that cost will have to borne by copyright holders is, unfortunately, still not very clear.  For ISPs, this decision is a mixed bag – Rogers makes a solid argument that the costs of compliance with Norwich orders are relatively high, compared with the automated notice-and-notice procedures. While it will benefit ISPs to be able to charge some of these fees to the copyright owner, we don’t have clear guidance on the specifics.  The matter will have to be determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the ISP and their own internal procedures.

Looking for advice on Norwich orders and enforcement against online copyright infringement? Look for experienced counsel to guide you through this process.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No commentsAI and Copyright and Art

.

By Richard Stobbe

At the intersection of this Venn diagram  [ Artificial Intelligence + Copyright + Art ] lies the work of a Paris-based collective.

By means of an AI algorithm, these artists have generated a series of portraits that have caught the attention of the art world, mainly because Christie’s, the auction house,  has agreed to place these works of art on the auction block. Christie’s markets themselves as “the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm”. The series of portraits is notionally “signed” (ð’Žð’Šð’ ð‘® ð’Žð’‚ð’™ ð‘« ð”¼ð’™ [ð’ð’ð’ˆ ð‘« (ð’™))] + ð”¼ð’› [ð’ð’ð’ˆ(ðŸ − ð‘«(ð‘®(ð’›)))]), denoting the algorithm as the author.

We have an AI engine that was programmed to analyze a range of prior works of art and create a new work of art. So where does this leave copyright? Clearly, the computer software that generated the artwork was authored by a human; whereas the final portrait (if it can be called that) was generated by the software. Can a work created by software enjoy copyright protection?

While Canadian courts have not yet tackled this question, the US Copyright Office in its Compendium of US Copyright Office Practices has made it clear that copyright requires human authorship: “…when a work is created with a computer program, any elements of the work that are generated solely by the program are not registerable…”

This is reminiscent of the famous “Monkey Selfie” case that made headlines a few years ago, where the Copyright Office came to the same conclusion: without a human author, there’s no copyright.

Calgary – 0:700 MST

Photo Credit: Obvious Art

No comments

Artist Sues for Infringement of “Moral Rights”

By Richard Stobbe

AÂ professional photographer sued the gallery that sold his works, and won a damage award for copyright infringement, infringement of moral rights, and punitive damages. In this case (Collett v. Northland Art Company Canada Inc., 2018 FC 269 (CanLII)), Mr. Collett, the photographer, alleged that his former gallery, Northland, infringed his rights after their business relationship broke down.

We don’t see many “moral rights” infringement cases in Canada, so this case is of interest for artists and other copyright holders for this reason alone. What are “moral rights”?

In Canada the Copyright Act tells us that the author of a work has certain rights to the integrity of the work, the right to be associated with the work as its author by name or under a pseudonym and the right to remain anonymous.

These so-called moral rights of the author to the integrity of a work can be infringed where the work is “distorted, mutilated or otherwise modified” ina way that compromises or prejudices the author’s honour or reputation, or where the work is used in association with a product, service, cause or institution that harms the authors reputation. Determining infringement has a highly subjective aspect, which must be established by the author. But this type of claim also has an objective element requiring a court to evaluate the prejudice or harm to the author’s “honour or reputation” which can be supported by public or expert opinion.

Here, the court found that the gallery had infringed Mr. Collett’s moral rights when the gallery intentionally reproduced one print entitled “Spirit of Our Land†and attributed the work to another artist. By reproducing “Spirit of Our Land†without Mr. Collett’s permission, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in the work. By attributing the reproductions to another artist, the gallery infringed the artist’s moral right “to be associated with the work as its authorâ€. This is actually a useful illustration of the difference between these different types of artist’s rights.

The unauthorized reproductions sold by the gallery were apparently taken from a copy resulting in images of lower resolution and therefore inferior quality, compared to authorized prints; unfortunately, we don’t have any insight into whether inferior quality would also infringed the artist’s moral right to the integrity of the work. The court declined to comment on this aspect since it had already concluded that moral rights were infringed when the prints were sold under the name of another artist.

Lastly, and interestingly, the court found that a link from the gallery’s site to the artist’s website constituted an infringement of copyright. It’s difficult to see how a link, without more, could constitute a reproduction of a work, unless the linked site was somehow framed or otherwise replicated within the gallery’s site. The evidence is not clear from reading the decision but the artist’s allegation was that the gallery “reproduced the entirety” of certain pages from the artist’s site, which created the false impression that the gallery still represented the artist. The court noted that the gallery continued to maintain a link to Mr. Collett’s website “knowing it was not authorized to do so.” By doing so, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in his site, including a reproduction of certain prints. Maintaining such a link was not found to constitute a breach of the artist’s moral rights.

In the end, statutory damages of $45,000 were awarded for breach of copyright, $10,000 for infringement of moral rights, and $25,000 for punitive damages to punish the gallery for its planned, deliberate and ongoing acts of infringement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 3)

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1 and Part 2, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

In the final part, we review the next couple of areas:

- Copyright

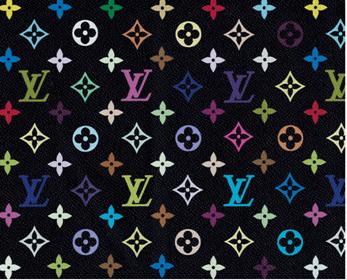

Copyright is a very flexible and wide-ranging tool to use in the fashion and apparel industry.  Under the Copyright Act, a business can use copyright to protect original expression in a range of products including artistic works, fabric designs, two and three-dimensional forms, and promotional materials, such as photographs, advertisements, audio and video content. For example, in Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. et al. and Singga Enterprises (Canada) Inc., the Federal Court sent a strong message to counterfeiters. This was a case of infringement of copyright , arising from the sale of counterfeit copies of Louis Vuitton and Burberry handbags through online sales and operations in Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton. Louis Vuitton owns copyright in the following Multicolored Monogram Print pattern:

Since the Copyright Act provides for an award of both damages and profits from the sale of infringing goods, or statutory damages between $500 to $20,000 per infringed work, the copyright owner had a range of options available to enforce its IP rights. In this case, the Federal Court awarded Louis Vuitton and Burberry a total of over $2.4 million in damages against the defendants, catching both the corporate and personal defendants in the award.

- Personality Rights

In Canada, the use of a famous person’s personality for commercial gain without authorization can lead to liability for “misappropriation of personalityâ€. To establish a case of misappropriation of personality, three elements must be shown:

- The exploitation of personality is for a commercial purpose.

- The person in question is identifiable in the context; and

- The use of personality suggests some endorsement or approval by the person in question.

Just ask William Shatner who objected on Twitter when his name and caricature were used to promote a condo development in Ontario, in a way that suggested that he endorsed the project.

Canadian personality rights benefit from some protection at the federal level through the Trademarks Act and the Competition Act, and are protected in some provinces. B.C., Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec have privacy statutes that restrict the unauthorized commercial use of personality, although the various provincial statutes approach the issue slightly differently. Specific advice is required in different jurisdictions, depending on the circumstances.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright in Architectural Works: an update

By Richard Stobbe

Who owns the copyright in a building?  A few years ago, we looked at the issue of Copyright in House Plans, but let’s look at something bigger. Much bigger.

In Lainco inc. c. Commission scolaire des Bois-Francs, 2017 CF 825, the federal court reviewed a claim by an architectural engineering firm over infringement of copyright in the design for an indoor soccer stadium.

Lainco, the original engineers, sued a school board, an engineering firm, a general contractor and an architect, claiming that this group copied the unique design of Lainco’s indoor soccer complex. The nearly identical copycat structure built in neighbouring Victoriaville was considered by the court to be an infringement of the original Lainco design even though the copying covered functional elements of the structure. The court decided that such functional structures can be protected as “architectural works†under the Copyright Act, provided they comprise original expression, based on the talent and judgment of the author, and incorporate an architectural or aesthetic element.

The group of defendants were jointly and severally liable for the infringement damage award, which was assessed at over $700,000.

Make sure you clarify ownership of copyright in architectural designs with counsel to avoid these pitfalls.

Calgary – 07:00

No comments

IP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 2, let’s review the next couple of areas:

- Industrial Design or “Design Patentâ€:

I always tell my clients not to underestimate this lesser-known area of IP protection. It can be a very powerful tool in the IP toolbox. In both Canada (which uses the term industrial design) and the US (which refers to a design patent), this category of intellectual property only provides protection for ornamental aspects of the design of a product as long as they are not purely functional . To put this another way, features that are dictated solely by a utilitarian function of the article are ineligible for protection.

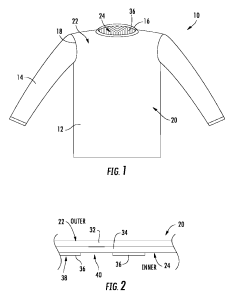

Registration is required and protection expires after 10 years. A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration. Some examples:  This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

The solid lines on the image above represents a protected design registration filed by Nike.

TIP: Placement of a pocket on a t-shirt may not be considered innovative, but even minor differentiators can help distinguish a product in a crowded field. A design registration can support a blended strategy which also deploys other IP protection, such as trademark rights.

- Trademarks:

Every consumer will be intuitively familiar with the power of a brand name such as LULULEMON or NIKE, or the well-known Nike Swoosh Design. That topic is well-covered elsewhere. However, some brands take advantage of a lesser-known area of trademark rights: distinguishing guise protects the shape of the product or its packaging. It differs from industrial design, and one way to consider the distinction is that an industrial design protects new ornamental features of a product from when it is first used, whereas a distinguishing guise can be registered once it has been used in Canada so long that becomes a brand, distinctive of a manufacturer due to extensive use of the mark in the marketplace. It’s worth noting that the in-coming amendments to the Trademarks Act will do away with distinguishing guises.

One good example is the well-known shape of CROCS-brand sandals. The shape and appearance of the footwear itself has been used so long that it now functions as a brand to distinguish CROCS from other sandals. Just as with industrial design, the protected features cannot be dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.

Others have filed distinguishing guise registrations in Canada, including Canada Goose Inc. for coats and Hermès International for handbags.

TIP: For a distinguishing guise application, each applicant will have to file evidence to show that the mark is distinctive in the marketplace in Canada. That is not the case with a regular trademark, such a word mark or regular logo design.

We review the final areas of IP protection in Part 3.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No comments

IP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 1)

.

By Richard Stobbe

Complex technology like blockchain is in fashion. What about IP protection for seemingly simple items like shirts, shoes and undergarments? As competitors jostle for position in the fashion and apparel marketplace, how do intellectual property rights apply? Make no mistake, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patent”

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 1, let’s review the first two areas:

- Confidential Information

Confidential information or ‘trade secrets’ refers simply to information that has value to a designer or manufacturer because competitors don’t have access to the information. As long as the information is kept secret, and is only disclosed to others in confidence, then the secrets may remain protected as ‘trade secrets’ for many years. The confidential information may be made up of related business information, such as contacts of suppliers, pricing margins, new product ideas or prototype designs. The period of confidentiality may be short-lived in the case of a new product design: once the product is released to customers, it’s no longer confidential.

An owner of confidential information must take steps to maintain confidentiality, and the information should only be disclosed under strict terms of confidentiality (as part of a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), or confidentiality agreement).

If the confidential information is misappropriated, the owner can seek to enforce its rights by proving that the information has the required quality of confidentiality, the information was disclosed in confidence, and there was an unauthorized use or disclosure in a way that caused harm to the owner.

TIP: Ensure that you take practical steps to limit access to the confidential info. And when signing an NDA, make sure it doesn’t contain any terms that might inadvertently compromise confidentiality or give away IP rights.

- Patents

Many apparel and footwear companies rely heavily on patent protection to block competitors and gain an advantage in the marketplace.

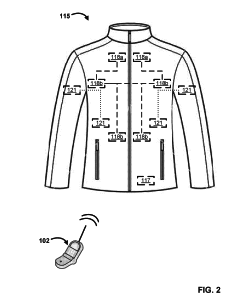

Let’s take a few examples. In pursuing the ‘holy grail’ of outdoor activewear, many manufacturers are seeking a comfortable, breathable jacket that can keep a wearer warm without overheating. The North Face System recently filed an application for a smart-sensing jacket using sensors to determine a “comfort signature” based on differences in environmental conditions between the sensors and making adjustments for the wearer.

A competitor – Under Armour Inc. – is seeking patent protection for garments incorporating printed ceramic materials to retain heat, without sacrificing other performance qualities such as  water and dirt repellency, durability, breathability and moisture-wicking qualities. In this patent application, Under Armour is seeking protection not only for the fabric but also the innovative method of manufacturing the fabric.

From high-tech jackets to innovative shoe designs, to more specific components, such as garment linings, or improved fasteners, patents can provide a valuable tool to ensure that a company’s research-and-development initiatives can bear fruit in the marketplace. By providing a period of exclusivity for the patent holder, this category of IP protection keeps the field clear of infringing replicas while the company recoups its investments and turns a profit on a successful product technology.

In the case of many fashion or apparel products, the time and cost of patent protection – it may take several years before a valid patent is issued – may not be justified in light of the high turn-over in seasonal product lines, and the ever-shifting tastes of consumers.

TIP: Make sure you consider both sides of the patent issue: as an inventor, an investment in patent protection may be worth considering, particularly in a product area where the underlying ‘technology’ or innovation may be commercialized over a number of years, such as the famous Gore-Tex fabric, even though superficial fashions may change during that time. On the flip side, manufacturers should take care to ensure that their own designs are not infringing the patent rights of some other patent holder.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 commentsCopyright Appeal Considers “User-Generated Content”

By Richard Stobbe

In 2015 an independent film-maker shot a film critical of the Vancouver aquarium, using some footage over which the Aquarium claimed copyright.  The Aquarium moved to block the online publication of the film.

Last year we wrote about that dispute and the preliminary injunction that prevented publication of parts of that documentary. In Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre v. Charbonneau, 2017 BCCA 395 (CanLII),  the preliminary order was appealed, and the documentary film-maker won. The decision is noteworthy for a number of reasons:

- In a preliminary injunction, at the “balance of convenience” analysis, freedom of expression should be weighed, particularly in a case such as this, where the documentary film engages a topic of public and social importance. The court affirmed that freedom of expression is among the most fundamental rights possessed by Canadians.

- The Copyright Act has an exception related to “user-generated content” under section 29.21 of the Act. This unique provision has been somewhat neglected by the courts since it was introduced in 2012.  This case remains the sole judicial consideration of section 29.21. At the lower level, the judge did not sufficiently analyze the issue of “fair dealing”, including whether this content qualified as non-commercial user-generated content under s. 29.21. However, we will still have to wait until a trial on the merits, to see how the court will deal with the bounds of non-commercial user-generated content under the Copyright Act.

The court sided with the documentary film-maker and set aside the earlier injunction. If this case goes to trial, it will finally provide some guidance on the application of section 29.21.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments