What happens to IP on bankruptcy?

By Richard Stobbe

The government introduced changes to some of the rules governing what happens to intellectual property on bankruptcy. If it becomes law, Budget Bill C-86 would enact changes to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) and the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) to clarify that intellectual property users can preserve their usage rights, even if:

- intellectual property rights are sold or disposed of in the course of a bankruptcy or insolvency proceeding, or

- if the trustee or receiver seeks to disclaim or cancel the license agreement relating to IP rights.

If the bankrupt company is an owner of IP, that owner has licensed the IP to a user or licensee, and the intellectual property is included in a sale or disposition by the trustee, the proposed changes in Bill C-86 make it clear that the sale or disposition does not affect the licensee’s right to continue to use the IP during the term of the agreement. This is conditional on the licensee continuing to perform its obligations under the agreement in relation to the use of the intellectual property.

The same applies if the trustee seeks to disclaim or resiliate the license agreement – such a step won’t impact the licensee’s right to use the IP during the term of the agreement as long as the licensee continues to perform its obligations under the agreement in relation to the use of the intellectual property.

These changes clarify and expand the 2009 rules in Section 65.11(7) of the BIA  and a similar provision in s. 32(6) of the CCAA. In particular, these amendments would extend the rules to cover sale, disposition, disclaimer or resiliation of an IP license agreement, whether by a trustee or a receiver.

This will solve the problem encountered in Golden Opportunities Fund Inc. v Phenomenome Discoveries Inc., 2016 SKQB 306 (CanLII), where the court noted that section 65.11(7) of the BIA was narrowly construed to only apply to trustees, and thus has no bearing on a court-appointed receivership.

Stay tuned for the progress of these proposed amendments.

Related Reading, if you’re into this sort of thing:

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentOwnership of Inventions by Employees

By Richard Stobbe

A group of employees invented a patentable invention. Advanced Video obtained the patent,  and then moved to sue a competitor for infringement. The alleged infringer challenged Advanced Video’s right to sue, pointing out that Advanced Video did not have standing to sue for infringement, since it never obtained the transfer of patent rights from the employee-inventor.

The U.S. case Advanced Video Technologies LLC v. HTC Corporation reviews the narrow issue of whether a co-inventor of the patent transferred her co-ownership interests in the patent under the terms of an employment agreement.

The patent in question listed three co-inventors: Benny Woo, Xiaoming Li, and Vivian Hsiun. The invention was created while the three co-inventors were employed with Infochips Systems Inc. (“Infochips”), a predecessor of Advanced Video. Through a series of steps, two of the inventors, Mr. Woo and Ms. Li assigned their coownership interests in the patent to Advanced Video. The co-ownership interests of Ms. Hsiun were the subject of this lawsuit. Advanced Video claimed that it obtained Ms. Hsiun’s co-ownership interests in the invention through the original employment agreement with that employee.

A review of Ms. Hsiun’s employment agreement indicated that the clause in question was pretty clear:

I agree that I will promptly make full written disclosure to the Company, will hold in trust for the sole right and benefit of the Company, and will assign to the Company all my right, title, and interest in and to any and all inventions, original works of authorship, developments, improvements or trade secrets which I may solely or jointly conceive or develop or reduce to practice, or cause to be conceived or developed or reduced to practice, during the period of time I am in the employ of the Company. (Emphasis added)

For emphasis, the employment agreement went on to say:

I hereby waive and quitclaim to the Company any and all claims, of any nature whatsoever, which I now or may hereafter have infringement [sic] of any patents, copyrights, or mask work rights resulting from any such application assigned hereunder to the Company. (Emphasis added)

Translation? The employee agrees that she will assign to the employer all rights to any and all inventions developed by the employee during employment.

Surprisingly, the court decided this language did not clearly convey the rights to the invention, since the word “will” invoked a promise to do something in the future and did not effect a present assignment of the rights.

This was merely a promise to assign, not an actual immediate transfer of the invention.

While this is a U.S. case, it neatly illustrates the risks associated with the fine print in employment agreements: to avoid the problem faced by Advanced Video, it’s valuable for employment agreements to automatically and immediately assign and transfer rights to inventions, and to avoid any language that suggests a future obligation or future promise to assign.

The lesson for business in any industry is clear: ensure that your employment agreements – and by extension, independent contractor and consulting agreements – are clear. Intellectual property and ownership of inventions should be clearly addressed. Get advice from experienced counsel to ensure that the IP legal issues are covered – including confidentiality, consideration, invention ownership, IP assignment, non-competition and non-solicitation.

Related Reading: Â Employee Ownership of Patentable Inventions

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

IP Assets After Death (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

Can an inventor be granted a patent posthumously?

The answer is a clear yes, as illustrated by the experience of one well-known inventor: Steve Jobs is named as an inventor on hundreds of U.S. utility and design patents, over 140 of which have been awarded since his death in 2011. The Patent Act provides for a patent to issue after the death of the inventor, and the issued patent rights would be treated  like any other asset of the inventor’s estate.

The Patent Act refers to “legal representatives†of an inventor which includes “heirs, executors, …assigns,… and all other persons claiming through or under applicants for patents and patentees of inventions.â€

There are a few important implications here: A patent may be granted posthumously to the personal representatives of the estate of the deceased inventor.

This also means that executors of the estate of a deceased inventor are entitled to apply for and be granted a patent under the Act. Employers can also benefit from patent rights granted in the name of a deceased inventor, where those rights have been assigned under contract during the life of the inventor, such as a contract of employment.

The term of the patent rights remain the same: 20 years from the filing date, regardless of the date of death of the inventor.

There are well-established rules on filing protocols in the case of deceased inventors, in both national and international phase applications: make sure you seek experienced counsel when facing this situation.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

The Blockchain Patent Gold Rush

By Richard Stobbe

The blockchain technology underlying BitCoin and other cryptocurrencies was originally designed and conceived as an open protocol that would not be owned by any one centralized entity, whether government or private. Just like other foundational protocols that were created in the early days of the internet (email is based on POP, SMTP and IMAP, and websites rely on HTTP, and file transfers use FTP and TCP/IP), no-one really owns these protocols.  No-one collects royalties or patent licensing fees for the use of these protocols (…though some patent assertion entities might argue otherwise).

Similarly, the peer-to-peer vision underlying “the blockchain” was conceptually directed to maintaining the integrity of peer-to-peer transactions that function outside the realm of a centralized overseer such as a bank or government registry. Where, traditionally, a bank served as the trusted and verifiable record of a transaction, the use of blockchain technology could provide an alternative trusted and verifiable record of a transaction. No bank required.

It should come as no surprise, then, that banks are rushing to own a piece of this space.

A recent U.S. report shows: “The financial industry dominates the list of the top ten blockchain-related patent holders. … Leading the list is Bank of America with 43 patents, MasterCard International with 27 patents, FMR LLC (Fidelity) with 14 patents, and TD Bank with 11 patents. Other major financial institutions with blockchain patents include Visa Inc. with 7 patents, American Express with 6 patents, and Nasdaq Inc. with 5 patents.” (Blockchain Patent Filings Dominated by Financial Services Industry, Posted on January 12, 2018Â

Will the privatization of blockchain technologies spur adoption of this technology in the business-to-business layer? Or will the patent gold rush merely erect proprietary fences in a way that constrains adoption?

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

A sale in Canada triggers exhaustion of patent rights in the US

By Richard Stobbe

“Patent exhaustion” is something we’ve reviewed before. To recycle an old line, the term “patent exhaustion†does not refer to the feeling you get when a patent agent talks for 3 hours about the process of a patentee traversing a rejection in reexamination proceedings.

Nope, this is the patent law concept that the first authorized, unrestricted sale of a patented item ends, or “exhausts,†the patent-holder’s right to ongoing control of that item, leaving the buyer free to use or resell the patented item without restriction. For example, if you buy a patented widget from the patent owner, you can resell that widget to your neighbour without fear of infringing the patent.

What if the widget is sold by the U.S. patent holder in Canada? Does this exhaust the patent rights in the U.S.?

The US Supreme Court has recently confirmed that when the holder of a U.S. patent sells an item in an unrestricted sale, the patent holder does not retain patent rights in that product, even where that sale takes place outside the US. Thus, an authorized sale of the patented article in Canada by the U.S. patent holder would trigger exhaustion of the U.S. patent rights. The U.S. Supreme Court has confirmed that “An authorized sale outside the United States, just as one within the United States, exhausts all rights under the [U.S.] Patent Act.”

See: IMPRESSION PRODUCTS, INC. v. LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC. (Decided May 30, 2017)

Calgary -07:00 MST

No commentsPatent Infringement for Listing on eBay?

By Richard Stobbe

A patent owner notices that knock-off products are listed for sale on eBay. The knock-offs appear to infringe his patent. When eBay refuses to remove the allegedly infringing articles. The patent owner sues eBay for patent infringement, claiming that eBay is infringing the patent merely by hosting the listings, since listing the infringing articles amounts to an infringing “sale†or an infringing “offer to sell†the patented invention.

These are the facts faced by a U.S. court in Blazer v. eBay Inc. which decided that merely listing the articles for sale does not constitute patent infringement by means of an infringing sale, where it’s clear that the articles are not owned by eBay and are not directly sold by eBay. In fact, in the eBay model the seller makes a sale directly to the buyer – eBay can be characterized as a platform for hosting third party listings, rather than a seller. Â

Some interesting points arise from this decision:

- Prior patent infringement cases involving Amazon and Alibaba have suggested that the court will look closely at how the items are listed. For example, in those earlier cases, the court noted the use of the term “supplier” to describe the party selling the item, whereas the word “seller” is used in the eBay model. The term “supplier” might be taken to mean that the listing party is merely supplying the item to the platform provider, such as Amazon or Alibaba, who then sells to the end-buyer. Whereas the term “seller” identifies that the listing party is entering into a separate transaction with the end-buyer, leaving the platform provider out of that buy-sell transaction.

- The court in Blazer was clear that it will look at the entire context of the exchange to determine not only if an offer is being made, but who is making the offer.

- The “Terms of Use” or “Terms of Service” will be scrutinized by the court to help with this determination. The eBay terms explicitly advise users that eBay is not making an offer through a listing, and eBay lacks title and possession of the items listed.

Related Reading: eBay Not Liable for Listing Infringing Products of Third-Party Sellers – Not an Offer to Sell by eBay

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsExperimental Use of an Invention

By Richard Stobbe

Inventors must take care that their invention is “new” for it to be patentable. That means the invention hasn’t been disclosed to the public. Trade show announcements, press releases, publications, offering the invention for sale – all of these can be considered a public disclosure, and if disclosure of the invention occurs before the date of filing of the patent application, this disclosure could defeat patentability, since the invention is no longer “new” for patenting purposes.

In Canada and the U.S. there is a 12-month grace period, so the date of prior disclosure is measured against this 12-month period: put another way, patentability may be lost if the invention was disclosed by the inventor more than one year before the filing date of the patent.

So how does this apply to experimental use? How can an inventor test new inventions and avoid the problems associated with public disclosure?

The recent decision in Bombardier Recreational Products Inc. v. Arctic Cat Inc. is interesting in a number of ways, but in this discussion I want to flag one element of the case. Arctic Cat was sued by Bombardier for infringement of certain snowmobile patents, which related to a particular configuration of rider position and frame construction.  Arctic Cat raised a number of defenses and one of them was “prior public disclosure.” Since Bombardier, the patent-holder, tested its prototypes of the snowmobiles on public trails, Arctic Cat argued that, in and of itself, constituted public disclosure, since “someone could have witnessed the rider’s hips above his knees, and the ankles behind the knees, and the hips behind the ankles.”

Unhappily for Arctic Cat, the court dryly dismissed this defense as “another one of those last-ditch efforts.”

Citing an inventor’s freedom to engage in “reasonable experimentation”, the court went on to say: “Since at least 1904, our law has recognized the need to experiment in order to bring the invention to perfection. …In this case, the evidence is that [Bombardier] was conscious of the need for confidentiality and took steps to ensure it would be protected. The experimentation was necessary in view of the many uses that would be available for that new configuration.”

The court noted that, even if a member of the public could have seen the prototype snowmobile “there is little information that is made available to the public while riding the snowmobile on a trail, even for the person skilled in the art. The necessary information to enable is not made available. The invention disclosed in the Patents is not understood, its parameters are not accessible and it would not be possible to reproduce the invention on the simple basis that a snowmobile has been seen on a trail.”

Applying the well-recognized experimental use exception, the court found that experimental use on a public trail did not constitute prior public disclosure of the inventions. Inventors should take care to handle experimental use very carefully.  Make sure you get advice on this from experienced IP advisors.

Related Reading:Â A Distinctly Canadian Patent Fight

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsDrone Patents

By Richard Stobbe

Last month, Amazon made its first delivery via drone with its Prime Air service. Remember, this is an e-commerce company not a drone manufacturer. Amazon is pushing the limits in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and is laying the groundwork for an IP protection portfolio for this technology, even where it does not apparently benefit Amazon’s core business. This shows that innovation can open up other product channels that could be licensed, for example, to drone manufacturers. For instance, Amazon’s newest issued patent relates to a mini-drone to assist in police enforcement. Think of a traffic stop which is accompanied by the whine of a small pocket-sized drone that can monitor and record the interaction or chase bad guys.

Other innovations are squarely within Amazon’s core competencies of order fulfillment. Another recently issued patent seeks to protect drones from being hacked and rerouted en route.

Another application filed in April 2016 describes an aerial blimp-like order fulfillment center utilizing UAVs to deliver items from above. This shows that the growth in drone-related patents will not all be related directly to the individual drones, but rather will relate to the evolving ecosystem around the use of UAVs, including remote control technologies, payload innovations, docking infrastructure, and commercial deployments such as the Death Star of e-commerce.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsIP Licenses & Bankruptcy Laws (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

When a company goes through bankruptcy, it’s a process that can up-end all of the company’s contractual relationships. When that bankrupt company is a licensor of intellectual property, then the license agreement can be one of the contracts that is impacted. A recent decision has clarified the rights of licensees in the context of bankruptcy.

In our earlier post – Changes to Canada’s Bankruptcy Laws – we reviewed changes to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) back in 2009. These changes have now been interpreted by the courts, some seven years later.

In Golden Opportunities Fund Inc. v Phenomenome Discoveries Inc., 2016 SKQB 306 (CanLII),  the court reviewed a license between a parent and its wholly-owned subsidiary. Through a license agreement, a startup licensor, which was the owner of a patent covering an invention pertaining to the testing and analysis of blood samples, licensed a patented invention to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Phenomenome Discoveries Inc. (PDI). PDI, in turn was the owner of any improvements that it developed in the patented invention, subject to a license of those improvements back to the parent company.

PDI went bankrupt. The parent company objected when the court-appointed receiver tried to sell the improvements to a new owner, free and clear of the obligations in the license agreement. In other words, the parent company wanted the right to continue its use of the licensed improvements and objected that the court-appointed receiver tried to sell those improvements without honoring the existing license agreement.

In particular, the parent company based its argument on those 2009 changes to Canada’s bankruptcy laws, arguing that licensees were now permitted keep using the licensed IP, even if the licensor went bankrupt, as long as the licensee continues to perform its obligations under the license agreement. Put another way, the changes in section 65.11 of the BIA should operate to prohibit a receiver from disclaiming or cancelling an agreement pertaining to intellectual property. The court disagreed.

The court clarified that “Section 65.11(7) of the BIA has no bearing on a court-appointed receivership.” Instead the decision in “Body Blue continues to apply to licences within the context of court-appointed receiverships. Licences are simply contractual rights.” (Note, the Body Blue case is discussed here.)

The court went on to note that a receiver is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts. The only limitation is that a receiver cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, IP license agreements do not grant a property right, but are merely a contractual right to use. Court-appointed receivers can disclaim these license agreements and can sell or dispose of the licensed IP free and clear of the license obligations, despite the language of Section 65.11(7) of the BIA.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

3 comments

How long does it take to get a patent?

By Richard Stobbe

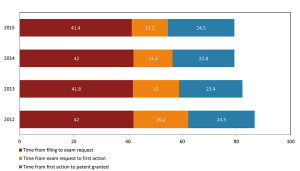

Patent advisors are often asked this question. In Canada, CIPO has published the first-ever IP Canada Report, which contains an interesting trove of IP statistics. Among the infographics and pie-charts is a series of bar graphs showing the time to issuance for Canada patents.

Figure 25 – Average time period in months for the three main stages of the patent process (Courtesy of CIPO)

Over the past four years, the patent office in Canada has been able to shave months off the delivery time, but the average is still in the neighbourhood of 80 months, or roughly 6 1/2 years. Â Certainly some patents will issue sooner, in the 3 – 4 year range, and some will take much longer. Â There are strategies to influence (to some degree) the pace of patent prosecution.

And remember, this is the time to issuance from filing. The time to prepare and draft the application must also be factored in.

Ensure that you get advice from your patent agent and budget for this period of time, it’s a commitment. Â More questions on patenting your inventions? Contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsLicensees Beware: assignment provisions in a license agreement

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say a company negotiates a patent license agreement with the patent owner. The agreement includes a clear prohibition against assignment – in other words, for either party to transfer their rights under the agreement, they have to get the consent of the other party. Â So what happens if the underlying patent is transferred by the patent owner?

The clause in a recent case was very clear:

Neither party hereto shall assign, subcontract, sublicense or otherwise transfer this Agreement or any interest hereunder, or assign or delegate any of its rights or obligations hereunder, without the prior written consent of the other party. Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect. This Agreement shall be binding upon, and shall inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective successors and heirs. [Emphasis added]

That was the clause appearing in a license agreement for a patented waterproof zipper between YKK Corp. and Au Haven LLC, the patent owner.  YKK negotiated an exclusive license to manufacture the patented zippers in exchange for a royalty on sales. Through a series of assignments, ownership of the patent was transferred to a new owner, Trelleborg. YKK, however, did not consent to the assignment of the patent to Trelleborg. The new owner later joined Au Haven and they both sued YKK for breach of the patent license agreement as well as infringement of the licensed patent.

YKK countered, arguing that Trelleborg (the patent owner) did not have standing to sue, since the purported assignment was void, according to the clause quoted above, due to the fact that YKK’s consent was never obtained: “Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect.” (Emphasis added) In other words, Â YKK argued that since the attempted assignment of the patent was done without consent, it was not an effective assignment, and thus Trelleborg was not the proper owner of the patent, and thus had no right to sue for infringement of that patent.

The court considered this in the recent US decision in Au New Haven LLC v. YKK Corporation (US District Court SDNY, Sept. 28, 2016) (hat tip to Finnegan). Rejecting YKK’s argument, the court found that the clause did not prevent assignments of the underlying patent or render assignments of the patent invalid, since the clause only prohibited assignments of the agreement and of any interest under the agreement, and it did not specifically mention the assignment of the patent itself.

Thus, the transfer of the patent (even though it was done without YKK’s consent) was valid, meaning Trelleborg had the right to sue for infringement of that patent.

Both licensors and licensees should take care to consider the consequences of the assignment provisions of their license, whether assignment is permitted by the licensee or licensor, and whether assignment of the underlying patent should be controlled under the agreement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsBrexit’s impact on IP Rights

By Richard Stobbe

The  UK’s Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA) has released a helpful 12-page summary entitled The Impact of Brexit on Intellectual Property, which discusses a number of IP topics and the anticipated impact on IP rights and transactions, including:

- EPC, PCT and UK patents

- Community trade marks

- Trade secrets

- Copyright

- IP disputes and IP transactions

It is CIPA’s position that IP rights holders should expect “business as usual” in the next few years, since existing UK national IP rights are unaffected, European patents and applications remain unaffected, and the UK Government has not even taken steps to trigger “Article 50” which would put in motion the formal bureaucratic machinery to leave the EU. This step is not expected until late 2016 or early 2017, which means the final exit may not occur until 2019.

Canadian rightsholders who have UK or EU-based IP rights are encouraged to consult IP counsel regarding their IP rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 comment

Protective Order for Source Code

By Richard Stobbe

A developer’s source code is considered the secret recipe of the software world – the digital equivalent of the famed Coca-Cola recipe. In Google Inc. v. Mutual, 2016 BCSC 1169 (CanLII),  a software developer sought a protective order over source code that was sought in the course of U.S. litigation. First, a bit of background.

This was really part of a broader U.S. patent infringement lawsuit (VideoShare LLC v. Google Inc. and YouTube LLC) between a couple of small-time players in the online video business: YouTube, Google, Vimeo, and VideoShare. In its U.S. complaint, VideoShare alleged that Google, YouTube and Vimeo infringed two of its patents regarding the sharing of streaming videos. Google denied infringement.

One of the defences mounted by Google was that the VideoShare invention was not patentable due to “prior art†– an invention that predated the VideoShare patent filing date.  This “prior art” took the form of an earlier video system, known as the POPcast system.  Mr. Mutual, a B.C. resident, was the developer behind POPcast. To verify whether the POPcast software supported Google’s defence, the parties in the U.S. litigation had to come on a fishing trip to B.C. to compel Mr. Mutual to find and disclose his POPcast source code. The technical term for this is “letters rogatory” which are issued to a Canadian court for the purpose of assisting with U.S. litigation.

Mr. Mutual found the source code in his archives, and sought a protective order to protect the “never-public back end Source Code filesâ€, the disclosure of which would “breach my trade secret rights”.

The B.C. court agreed that the source code should be made available for inspection under the terms of the protective order, which included the following controls. If you are seeking a protective order of this kind, this serves as a useful checklist of reasonable safeguards to consider.

Useful Checklist of Safeguards

- The Source Code shall initially only be made available for inspection and not produced except in accordance with the order;

- The Source Code is to be kept in a secure location at a location chosen by the producing party at its sole discretion;

- There are notice provisions regarding the inspection of the Source Code on the secure computer;

- The producing party is to test the computer and its tools before each scheduled inspection;

- The receiving party, or its counsel or expert, may take notes with respect to the Source Code but may not copy it;

- The receiving party may designate a reasonable number of pages to be produced by the producing party;

- Onerous restrictions on the use of any Source Code which is produced;

- The requirement that certain individuals, including experts and representatives of the parties viewing the Source Code, sign a confidentiality agreement in a form annexed to the order.

A Delaware court has since ruled that VideoShare’s two patents are invalid because they claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments“Wow Moments” and Industrial Design Infringement

By Richard Stobbe

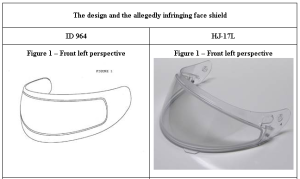

An inventor had a “wow” moment when he came across a design improvement for cold-weather visors – something suitable for the snowmobile helmet market. The helmet maker brought the improved helmet to market and also pursued both patent and industrial design protection. The patent application was ultimately abandoned, but the industrial design registration was issued in 2010 for the “Helmet Face Shield†design, which purports to protect the visor portion of a snowmobile helmet.

AFX Licensing, the owner of the invention, sued a competitor for infringement of the registered industrial design. AFX sought an injunction and damages for infringement under the Industrial Design Act.  The competitor – HJC America – countered with an application to expunge the registration on the basis of invalidity. HJC argued that the design was invalid due to a lack of originality and due to functionality.

Can a snowmobile visor be protected using IP rights?

A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration.

In AFX Licensing Corporation v. HJC America, Inc., 2016 FC 435 (CanLII),  the court decided that AFX’s industrial design registration was valid but was not infringed by the HJC product because the court saw “substantial differences” between the two designs. In summarizing, the court noted the following:

“First, the protection offered by the industrial design regime is different from that of the patent regime…Â the patent regime protects functionality and the design regime protects the aesthetic features of any given product.” (Emphasis added)

The industrial design registration obtained by AFXÂ does “not confer on AFX a monopoly over double-walled anti-fogging face shields in Canada. Rather, it provides a measure of protection for any shield that is substantially similar to that depicted in the ID 964 illustrations, and it cannot be said that the HJ-17L meets that threshold.”

The infringement claim and the expungement counter-claim were both dismissed.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsBREXIT and IP Rights for Canadian Business

By Richard Stobbe

Yesterday UK voters elected to approve a withdrawal from the EU.  What does this mean for Canadian business owners who have intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK?

The first message for Canadian IP rights holders is (in true British style) remain calm and keep a stiff upper lip. All of this is going to take a while to sort out and rights holders will have advance notice of the various means to protect their rights in an orderly fashion. The British are not known for rash actions — ok, other than the Brexit vote.

Rights granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), will be impacted, although the extent of the impact is still to be negotiated and settled. The UK’s membership in WIPO (the World International Property Organisation) is independent of EU membership and so will not be affected by this process. Similarly, the UK’s participation in the European Patent Convention is not dependent on EU membership.

Current speculation is that EU Trade Marks will continue to be recognized as valid in the EU, although such rights will not be recognized in the UK. This may require Canadian rights holders to submit new applications for those marks in the UK, or there may be a negotiated conversion of those EUIPO rights into national UK rights, permitting these registered marks to be recognized both in the EU and the UK.

Copyright law should not be dramatically impacted, since many of the rights of Canadian copyright holders would benefit from international copyright conventions that predate the EU era. However, UK copyright law was undergoing a process to become aligned with EU laws. For example, recent amendments to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were enacted in 2014 to implement EU Directive 2001/29, and the fate of these statutory amendments remains unclear at the moment.

Again, this won’t happen overnight.  Many bureaucrats must debate many regulations before the way forward becomes clear. That’s not much of a rallying cry but it is the reality for an unprecedented event such as this. The good news? If you are a EU IP rights negotiator, you will have steady employment for the next few years.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments

The IP Dimensions of 3D Printing: a recent decision

By Richard Stobbe

There has been much speculation about the impact of 3D printing on the enforcement of IP rights. But very few decisions. Now, finally, a case you can sink your teeth into: ClearCorrect v. ITC, 2014-1527 deals squarely with a patent infringement allegation which focuses on 3D-printing technology.

This case relates to the production of orthodontic appliances known as teeth aligners. According to patents owned by Align Technology, their aligners “are configured to be placed successively on the patient’s teeth and to incrementally reposition the teeth from an initial tooth arrangement, through a plurality of intermediate tooth arrangements, and to a final tooth arrangement…†as listed in the ’880 patent. (As soon as you see the word “plurality”, you just know you’re reading a good patent.)

ClearCorrect, a competitor of Align Technology, produced aligners by means of 3D-printed digital models of aligners. ClearCorrect electronically transmitted digital files to its subsidiary ClearCorrect Pakistan (thus skirting the US patent rights) where digital models of the aligners were created and configured. ClearCorrect Pakistan then electronically transmitted these digital models back to ClearCorrect US, where the digital models were 3D-printed into physical models. From there, aligners were manufactured using the physical models.

The patent owner alleged that the transmission of these digital three-dimensional models should be stopped at the border, just like any infringing “article” would be stopped. Typically, an owner of US patent rights can employ the resources of the ITC to stop and seize articles – take for example, a piece of equipment or a consumer product – which infringes a US patent. This prevents the infringing articles from being imported into the US, even if they are manufactured overseas. In this case, the court had to decide if digital three-dimensional files constituted “articles” for these purposes.

In the end, the court considered articles to be “material things” and decided that the 3D-printable digital files were not “articles”. Thus, the ITC lacked jurisdiction to prevent the entry of these files into the US. (Exactly how it could prevent the transmission of the files is another matter entirely.)

Something to chew on while we wait to see if the decision will be appealed.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsAmendments to Canadian Intellectual Property Laws …Delayed

.

By Richard Stobbe

As an update to our earlier post, we note that the Intellectual Property Institute of Canada, in its most recent bulletin, is estimating that the anticipated changes to Canada’s intellectual property laws – including the overhaul of trademark laws under new Trademarks Regulations, as well as changes to the Patent Rules and Industrial Design Regulations – will not begin until late 2016. This pushes the patent law changes into late 2017, with the trademark amendments to be implemented by early 2018.

The impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) on Canada’s IP laws is still being assessed. If ratified in Canada, the TPP is expected to require further consequential amendments to Canadian laws – such as copyright term extensions.

Stay tuned. Just don’t hold your breath.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsInfringing Sales Through Amazon

.

By Richard Stobbe

A U.S. court recently decided that it would take jurisdiction over a seller who sold allegedly infringing products through online retailers such as Amazon.com. PetEdge Inc. a Massachusetts-based manufacturer, owns a patent and certain trademarks for its folding steps to enable pets to climb onto a bed.

Alleging patent and trademark infringement, PetEdge wanted to sue rival Fortress Secure Solutions, based in Washington State, a company with no operations, personnel or offices in Massachusetts.

To justify its lawsuit in Massachusetts district court, PetEdge argued – and the court agreed – that Fortress purposefully directed its sales to Massachusetts residents by making its sales through Amazon.com, and the infringement claims arose from those activities. Thus, the court took jurisdiction over the out-of-state defendant.

Lessons for business?

Canadian retailers should take note that if they use national retailers such as Amazon.com to sell products into the U.S., the use of this distribution channel could result in a local state court taking jurisdiction over the Canadian seller, under the same analysis applied to Fortress.

Thanks to Finnegan LLP for their link to the decision: PetEdge, Inc. v. Fortress Secure Solutions, LLC

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsPatent Update: Infringement and “Non-Infringing Alternatives”

By Richard Stobbe

If you are a patent owner, you are entitled to damages if someone infringes your patent. The measure of damages is compensatory damages, lost profits or a “reasonable royalty”. Is it fair for the infringer to say that the damages should be reduced because the infringer could have made the same sales using an available alternative that did not infringe the patent?

Marck sued its rival Apotex for patent infringement for sales of the drug lovastatin. The trial judge awarded Merck a total damages award of $119 million. In the decision in Apotex Inc. v. Merck & Co., Inc. 2015 FCA 171, the court considered Apotex’s argument about “non-infringing alternatives”. In a nutshell, Apotex was saying, okay, we infringed when we sold lovastatin using the patent process, but we could have made the same sales of lovastatin using another process that did not infringe. Therefore, the measure of damages should be lower, since the loss of profits could still have been suffered by the patent holder without any patent infringement.

The court describes it this way: “The principal issue raised on this appeal is whether, when calculating damages for patent infringement, it is relevant to consider the availability of non-infringing alternative products available to the infringer. For the reasons that follow I have concluded that, as a matter of law, the availability of a non-infringing alternative is a relevant consideration. The issue arises in the following context: Apotex has been found liable for patent infringement. On the issue of remedy, Apotex submits that the damages it is liable for should be reduced because it had available a non-infringing product that it could and would have used.” (Emphasis added) In other words, the patent holder’s sales could have been reduced simply by legitimate competition as opposed to infringement. In the end, the court agreed that non-infringing alternatives should be considered, but disagreed that there was any non-infringing alternative available in this case.

The damages award (one of the largest damage awards in Canada) remained in place and Apotex’s appeal was dismissed. This kicks open the door to arguments about using “non-infringing alternatives” to reduce damages in future patent infringement lawsuits.

Calgary – 05:00 MT

No commentsEmployee Ownership of Patentable Inventions

By Richard Stobbe

A startup in the oil-and-gas service sector sought to improve downhole well stimulation technology. After a few years, differences between the three founders culminated in the ouster of Mr. Groves, one of the founders. Mr. Groves was removed as President and then his employment was terminated. The company had, during those few years, filed for patent protection on a number of inventions which were invented by Mr. Groves. After his termination, he promptly sued his former employer based on a claim of ownership of those inventions which were created during the course of his employment.

In the recent decision in Groves v Canasonics Inc., 2015 ABQB 314 (CanLII), the court noted that the employment agreement between Mr. Groves and Canasonics included the following condition:

“The Company shall own any and all Copyright and Intellectual Property created in the course of Employment. Further, in the event there is a period when the Employee might be considered an independent contractor, all Copyright created and any Intellectual Property created shall be owned by the Company.” The Court had no trouble in concluding that the inventions were patented in the U.S. and Canada by their inventor, Mr. Groves in his capacity as an employee, who then assigned the inventions to Canasonics as the employer pursuant to terms of the employment agreement.

The lesson for business in any industry is clear: ensure that your employment agreements – and by extension, independent contractor and consulting agreements – are clear. Intellectual property and ownership of inventions should be clearly addressed. Get advice from experienced counsel to ensure that the IP legal issues are covered – including confidentiality, consideration, invention ownership, IP assignment, non-competition and non-solicitation.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

1 comment