“Place of origin” as a trademark in Canada

By Richard Stobbe

The Canadian trademarks office has released a Practice Notice in order to clarify current practice with respect to applying the descriptiveness analysis to geographical names.

In our earlier post on this topic (Trademark Series: Can a Geographical Name be a Trademark?), we noted that a geographical name can be registrable as a trademark in Canada. The issue is whether the term is “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive†in the English or French languages of the place of origin of the goods or services.

The Practice Notice tells us that a trademark will be considered a “geographic name” if the examiner’s research shows “that the trademark has no meaning other than as a geographic name.” It’s unclear what this research would consist of. (A search in Google Maps? An atlas?)

Even if the mark does have other meanings, other than as a place name, the mark will be still considered a geographical name if the trademark “has a primary or predominant meaning as a geographic name. The primary or predominant meaning is to be determined from the perspective of the ordinary Canadian consumer of the associated goods or services. If a trademark is determined to be a geographic name, the actual place of origin of the associated goods or services will be ascertained by way of confirmation provided by the applicant.” (Emphasis added)

In some case, the “actual origin” of products may be easy to determine – where, for example, apples are grown in British Columbia, then it stands to reason that “British Columbia” would be clearly descriptive of the place of origin and thus clearly descriptive of the goods. Apples are likely to be grown and harvested in one location. But how would one determine the “actual origin” of, say, a laptop which is designed in California, with parts from Taiwan and China, assembled in Thailand?

If the examiner decides that the geographic name is the same as the actual place of origin of the products, the trademark will be considered “clearly descriptive” and unregistrable. If the geographic name is NOT the same as the actual place of origin of the goods and services, the trademark will be considered “deceptively misdescriptive” since the ordinary consumer would be misled into the belief that the products originated from the location of that geographic name.

It’s worth noting that the place of origin of the products is not the same as the address of the applicant. The applicant’s head office is irrelevant for these purposes.

Need assistance navigating this area? Contact experienced trademark counsel.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsUse of a Trademark on Software in Canada

.

By Richard Stobbe

Xylem Water Solutions is the owner of the registered Canadian trademark AQUAVIEW in association with software for water treatment plants and pump stations. Â Xylem received a Section 45 notice from a trademark lawyer, probably on behalf of an anonymous competitor of Xylem, or an anonymous party who wanted to claim the mark AQUAVIEW for themselves. This is a common tactic to challenge, and perhaps knock-out, a competitor’s mark.

A Section 45 notice under the Trade-marks Act requires the owner of a registered trademark to prove that the mark has been used in Canada during the three-year period immediately before the notice date. As readers of ipblog.ca will know, the term “use” has a special meaning in trademark law. In this case, Xylem was put to the task of showing “use” of the mark AQUAVIEW in association with software.

How does a software vendor show “use” of a trademark on software in Canada?

The Act tells us that “A trade-mark is deemed to be used in association with goods if, at the time of the transfer of the property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade, it is marked on the goods themselves or on the packages in which they are distributed…” (Section 4)

The general rule is that a trademark should be displayed at the point of sale (See: our earlier post on Scott Paper v. Georgia Pacific). In that case, involving a toilet paper trademark, Georgia-Pacific’s mark had not developed any reputation since it was not visible until after the packaging was opened. As we noted in our earlier post, if a mark is not visible at the point of purchase, it can’t function as a trade-mark, regardless of how many times consumers saw the mark after they opened the packaging to use the product.

The decision in Ashenmil v Xylem Water Solutions AB, 2016 TMOB 155 (CanLII),  tackles this problem as it relates to software sales. In some ways, Xylem faced a similar problem to the one which faced Georgia-Pacific. The evidence showed that the AQUAVIEW mark was displayed on website screenshots, technical specifications, and screenshots from the software.

The decision frames the problem this way: “…even if the Mark did appear onscreen during operation of the software, it would have been seen by the user only after the purchaser had acquired the software. Â … seeing a mark displayed, when the software is operating without proof of the mark having been used at the time of the transfer of possession of the ware, is not use of the mark” as required by the Act.

The decision ultimately accepted this evidence of use and upheld the registration of the AQUAVIEW mark. It’s worth noting the following take-aways from the decision:

- The display of a mark within the actual software would be viewed by customers only after transfer of the software. Â This kind of display might constitute use of the mark in cases where a customer renews its license, but is unlikely to suffice as evidence of use for new customers.

- In this case, the software was “complicated” software for water treatment plants. The owner sold only four licenses in Canada within a three-year period.  In light of this, it was reasonable to infer that purchasers would take their time in making a decision and would have reviewed the technical documentation prior to purchase.  Thus, the display of the mark on technical documentation was accepted as “use” prior to the purchase. This would not be the case for, say, a 99¢ mobile app or off-the-shelf consumer software where technical documentation is unlikely to be reviewed prior to purchase.

- Website screenshots and digital marketing brochures which clearly display the mark can bolster the evidence of use. Again, depending on the software, purchasers can be expected to review such materials prior to purchase.

- Software companies are well advised to ensure that their marks are clearly displayed on materials that the purchaser sees prior to purchase, which will differ depending on the type of software. The display of a mark on software screenshots is not discouraged; but it should not be the only evidence of use. If software is downloadable, then the mark should be clearly displayed to the purchaser at the point of checkout.

- The cases have shown some flexibility to determine each case on its facts, but don’t rely on the mercy of the court: software vendors should ensure that they have strong evidence of actual use of the mark prior to purchase. Clear evidence may even prevent a section 45 challenge in the first place.

To discuss protection for your software and trademarks, Â contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsDear CASL: When can I rely on “implied consent”?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation (CASL) is overly complex and notoriously difficult to interpret – heck, even lawyers start to see double when they read the official title of the law (An Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act).

The concept of implied consent (as opposed to express consent) is built into the law, and the trick is to interpret when, exactly, a company can rely on implied consent to send commercial electronic messages (CEMs). There are a number of different types of implied consent, including a pre-existing business or non-business relationship, and the so-called “conspicuous publication exemption”.

One recent administrative decision (Compliance and Enforcement Decision CRTC 2016-428 re: Blackstone Learning Corp.) focused on “conspicuous publication” under Section 10(9) of the Act. A company may rely on implied consent to send CEMs where there is:

- conspicuous publication of the email address in question,

- the email address is not accompanied by a statement that the person does not wish to receive unsolicited commercial electronic messages at the electronic address; and

- the message is relevant to the person’s business, role, functions, or duties in a business or official capacity.

In this case, Blackstone Learning sent about 380,000 emails to government employees during 9 separate ad campaigns over a 3 month period in 2014. The case against Blackstone by the CRTC did not dwell on the evidence – in fact, Blackstone admitted the essential facts. Rather, this case focused on the defense raised by Blackstone. The company pointed to the “conspicuous publication exemption” and argued that it could rely on implied consent for the CEMs since the email addresses of the government employees were all conspicuously published online.

However, the company provided very little support for this assertion, and it did not provide back-up related to the other two elements of the defense; namely, that the email addresses were not accompanied by a “no spam” statement, and that the CEMs were relevant to the role or business of the recipients. The CRTC’s decision provides some guidance on implied consent and “conspicuous publication”:

- The CRTC observed that “The conspicuous publication exemption and the requirements thereof set out in paragraph 10(9)(b) of the Act set a higher standard than the simple public availability of electronic addresses.” In other words, finding an email address online is not enough.

- First, the exemption only applies if the email recipient publishes the email address or authorizes someone else to publish it. Let’s take the example of a sales rep who might publish his or her email, and also authorize a reseller or distributor to publish the email address. However, the CRTC notes if a third party were to collect and sell a list of such addresses on its own then “this would not create implied consent on its own, because in that instance neither the account holder nor the message recipient would be publishing the address, or be causing it to be published.”

- The decision does not provide a lot of context around the relevance factor, or how that should be interpreted. CRTC guidance provides some obvious examples – an email advertising how to be an administrative assistant is not relevant to a CEO. Â In this case, Blackstone was advertising courses related to technical writing, grammar and stress management. Arguably, these topics might be relevant to a broad range of people within the government.

- Note that the onus of proving consent, including all the elements of the “conspicuous publication exception”, rests with the person relying on it. The CRTC is not going to do you any favours here. Make sure you have accurate and complete records to show why this exemption is available.

- Essentially, the email address must “be published in such a manner that it is reasonable to infer consent to receive the type of message sent, in the circumstances.” Those fact-sepecific circumstances, of course, will ultimately be decided by the CRTC.

- Lastly, the company’s efforts at compliance may factor into the ultimate penalty. Initially, the CRTC assessed an administrative monetary penalty (AMP) of $640,000 against Blackstone. The decision noted that Blackstone’s correspondence with the Department of Industry showed the “potential for self-correction” even if Blackstone’s compliance efforts were “not particularly robust”. These compliance efforts, among other factors, convinced the commission to reduce the AMP to $50,000.

As always, when it comes to CEMs, an ounce of CASL prevention is worth a pound of AMPs. Get advice from professionals about CASL compliance.

See our CASL archive for more background.

Calgary 07:00 MST

No commentsTrader Joe’s vs. Irate Joe’s

By Richard Stobbe

In a long-running battle between Trader Joe’s and _Irate Joe’s (formerly Pirate Joe’s, a purveyor of genuine Trader Joe’s products in Vancouver, B.C.), the US Circuit Court of Appeals recently weighed in. We originally covered this story a few years ago.

In Trader Joe’s Company v. Hallatt, an individual, dba Pirate Joe’s, aka Transilvania Trading [PDF], the court considered the extraterritorial reach of US trademarks laws. The Defendant, Michael Hallatt, didn’t deny that he purchased Trader Joe’s-branded groceries in Washington state, smuggled this contraband across the border, and then resold it in a store called “Pirate Joe’s” (although Hallatt later dropped the “P” to express his frustration with TJ’s). Trader Joe’s sued in U.S. federal court for trademark infringement and unfair competition under both the federal Lanham Act and Washington state law. Since Mr. Hallatt’s allegedly infringing activity took place entirely in Canada, the question was whether U.S. federal trademarks law would extend to provide a remedy in a U.S. Court.

In the wake of this decision, Trader Joe’s federal claims are kept alive, although the court dismissed the state law claims against Hallatt.

The court concluded: “We resolve two questions to decide whether the Lanham Act reaches Hallatt’s allegedly infringing conduct, much of which occurred in Canada: First, is the extraterritorial application of the Lanham Act an issue that implicates federal courts’ subject-matter jurisdiction? Second, did Trader Joe’s allege that Hallatt’s conduct impacted American commerce in a manner sufficient to invoke the Lanham Act’s protections? Because we answer “no†to the first question but “yes†to the second, we reverse the district court’s dismissal of the federal claims and remand for further proceedings.”

In plain English, the appeals court has asked the lower court to reconsider the federal claims and make a final decision. Grab a bag of Trader Joe’s Pita Crisps with Cranberries & Pumpkin Seeds … and stay tuned!

Calgary – 08:00 MST

No comments

Licensees Beware: assignment provisions in a license agreement

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say a company negotiates a patent license agreement with the patent owner. The agreement includes a clear prohibition against assignment – in other words, for either party to transfer their rights under the agreement, they have to get the consent of the other party. Â So what happens if the underlying patent is transferred by the patent owner?

The clause in a recent case was very clear:

Neither party hereto shall assign, subcontract, sublicense or otherwise transfer this Agreement or any interest hereunder, or assign or delegate any of its rights or obligations hereunder, without the prior written consent of the other party. Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect. This Agreement shall be binding upon, and shall inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective successors and heirs. [Emphasis added]

That was the clause appearing in a license agreement for a patented waterproof zipper between YKK Corp. and Au Haven LLC, the patent owner.  YKK negotiated an exclusive license to manufacture the patented zippers in exchange for a royalty on sales. Through a series of assignments, ownership of the patent was transferred to a new owner, Trelleborg. YKK, however, did not consent to the assignment of the patent to Trelleborg. The new owner later joined Au Haven and they both sued YKK for breach of the patent license agreement as well as infringement of the licensed patent.

YKK countered, arguing that Trelleborg (the patent owner) did not have standing to sue, since the purported assignment was void, according to the clause quoted above, due to the fact that YKK’s consent was never obtained: “Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect.” (Emphasis added) In other words, Â YKK argued that since the attempted assignment of the patent was done without consent, it was not an effective assignment, and thus Trelleborg was not the proper owner of the patent, and thus had no right to sue for infringement of that patent.

The court considered this in the recent US decision in Au New Haven LLC v. YKK Corporation (US District Court SDNY, Sept. 28, 2016) (hat tip to Finnegan). Rejecting YKK’s argument, the court found that the clause did not prevent assignments of the underlying patent or render assignments of the patent invalid, since the clause only prohibited assignments of the agreement and of any interest under the agreement, and it did not specifically mention the assignment of the patent itself.

Thus, the transfer of the patent (even though it was done without YKK’s consent) was valid, meaning Trelleborg had the right to sue for infringement of that patent.

Both licensors and licensees should take care to consider the consequences of the assignment provisions of their license, whether assignment is permitted by the licensee or licensor, and whether assignment of the underlying patent should be controlled under the agreement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsOnline Defamation & Libel: The Trump Effect

By Richard Stobbe

It’s not often that our little blog intersects with such titanic struggles as the U.S. presidential race – and by using the term “titanic” IÂ certainly don’t mean to suggest that anything disastrous is in the future.

After the New York Times published personal allegations of sexual assault against presidential candidate Donald Trump, the candidate’s lawyers promptly fired a shot across the bow, threatening legal action for libel and demanding that the article be removed from the Times’s website. Last week, the lawyer for the New York Times responded to lawyers for Mr.  Trump with a succinct defense of their publication of the article, arguing “We did what the law allows: We published newsworthy information about a subject of deep public concern.”

If this had happened in Canada, the law would almost certainly favour the position taken by the Times. In Quan v. Cusson, [2009] 3 SCR 712, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed the defense of “responsible communication on matters of public interest” permitting journalists to report on matters of public interest. That case, interestingly, dealt with an Ontario police officer who attended in New York City shortly after the events of September 11, 2001 in order to assist with the search and rescue effort at Ground Zero. The officer sued for defamation after a newspaper published articles alleging that he had misrepresented himself to the New York authorities and possibly interfered with the rescue operation. As noted by the CBA this defense of responsible journalism applies if:

- the news was urgent, serious, and of public importance,

- the journalist used reliable sources, and

- the journalist tried to get and report the other side of the story.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsHappy Birthday… in Trademarks

ipbog.ca turns 10 this month. It’s been a decade since our first post in October 2006 and to commemorate this milestone …since no-one else will… let’s have a look at IP rights and birthdays.

You may have heard that the lyrics and music to the song “Happy Birthday” were the subject of a protracted copyright battle. The lawsuit came as a surprise to many people, considering this is the “world’s most popular song” (apparently beating out Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven, but that’s another copyright story for another time).  Warner Music Group claimed that they owned the copyright to “Happy Birthday”, and when the song was used for commercial purposes (movies, TV shows, commercials), Warner Music extracted license fees, to the tune of $2 million each year. When this copyright claim was finally challenged, a US court ruled that Warner Music did not hold valid copyright, resulting in a $14 million settlement of the decades-old dispute in 2016.

In the realm of trademarks, a number of Canadian trademark owners lay claim to HAPPY BIRTHDAY including:

- The Section 9 Official Mark below, depicting a skunk or possibly a squirrel with a top hat, to celebrate Toronto’s sesquicentennial. Hey, don’t be too hard on Toronto, it was the ’80s.

- Another Section 9 Official Mark, the more staid “HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986” to celebrate that city’s centennial. Because nothing says ‘let’s party’ like the words HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986.

- Cartier’s marks HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA511885 and TMA779496) in association with handbags, eyeglasses and pens.

- Mattel’s mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA221857) in association with dolls and doll clothing.

- The mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY VINEYARDS (pending) for wine, not to be confused with BIRTHDAY CAKE VINEYARDS (also pending) also for wine.

- FTD’s marks BIRTHDAY PARTY (TMA229547) and HAPPY BIRTHTEA! (TMA484760) for “live cut floral arrangements”

- And for those who can’t wait until their full birthday there’s the registered mark HALFYBIRTHDAYÂ Â (TMA833899 and TMA819609) for greeting cards and software.

- The registered mark BIRTHDAY BLISS (TMA825157) for “study programs in the field of spiritual and religious development”.

- Let’s not forget BIRTHDAYTOWN (TMA876458) for novelty items such as “key chains, crests and badges, flags, pennants, photos, postcards, photo albums, drinking glasses and tumblers, mugs, posters, pens, pencils, stick pins, window decals and stickers”.

- Of course, no trademark list would be complete without including McDonald’s MCBIRTHDAY mark (TMA389326) for restaurant services.

So, pop open a bottle of branded wine and enjoy some live cut floral arrangements and a McBirthday® burger as you peruse a decade’s worth of Canadian IP law commentary.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

Brexit’s impact on IP Rights

By Richard Stobbe

The  UK’s Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA) has released a helpful 12-page summary entitled The Impact of Brexit on Intellectual Property, which discusses a number of IP topics and the anticipated impact on IP rights and transactions, including:

- EPC, PCT and UK patents

- Community trade marks

- Trade secrets

- Copyright

- IP disputes and IP transactions

It is CIPA’s position that IP rights holders should expect “business as usual” in the next few years, since existing UK national IP rights are unaffected, European patents and applications remain unaffected, and the UK Government has not even taken steps to trigger “Article 50” which would put in motion the formal bureaucratic machinery to leave the EU. This step is not expected until late 2016 or early 2017, which means the final exit may not occur until 2019.

Canadian rightsholders who have UK or EU-based IP rights are encouraged to consult IP counsel regarding their IP rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 comment

Craft Beer Trademarks (Part 2)

By Richard Stobbe

In Part 1 we noted the growth in the craft beer industry in Canada and the U.S., and how this has spawned some interesting trademark disputes.

The case of  Brooklyn Brewery Corp. v. Black Ops Brewing, Inc. (January 7, 2016) pitted New York-based Brooklyn Brewery Corporation against California-based Black Ops Brewing, Inc. in a fight over the use of the mark BLACK OPS for beer. Brooklyn Brewery established sales, since 2007, of its beer under the registered trademark BROOKLYN BLACK OPS (for $29.99 a bottle!). It objected to the use of the name BLACK OPS by the California brewery, which commenced operations in 2015.

The California brewery argued that a distinction should be made between the name of the brewery versus the names of individual beers within the product line, which had different identifying names such as VALOR, SHRAPNEL and the BLONDE BOMBER.  However, this argument fell apart under evidence that the term “Black Ops†appeared on each label of each of the above-listed beers, and there was clear evidence that the California brewery applied for registration of the mark BLACK OPS BREWING in association with beer in the USPTO.

The court was convinced that use of the marks “Black Ops Brewing,†“Black Ops,†and “blackopsbrewery.com†created “a likelihood that the consuming public will be confused as to who makes what product.” An preliminary injunction was issued barring Black Ops Brewing from selling beer using the name BLACK OPS.

Black Ops Brewing has since rebranded to Tactical Ops Brewing.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 comments

Alberta’s Prospectus Exemption For Start-Up Businesses

By Richard Stobbe

If you’re a start-up, raising money can feel like a full time job.

Alberta recently brought in a few rule changes which may be of interest: ASC Rule 45-517 Prospectus Exemption for Start-up Businesses (Start-up Business Exemption – PDF) (effective July 19, 2016) is designed to “facilitate capital-raising for small- and medium-sized enterprises on terms tailored to deliver appropriate safeguards for investors.” Second, Alberta is considering the adoption of Multilateral Instrument 45-108 Crowdfunding (MI 45-108) and opened it for a comment period in July.

Crowdfunding (MI 45-108)

If the crowdfunding rules are adopted for Alberta issuers, it would facilitate the distribution of securities through an online funding portal in Alberta as well as across any of the other jurisdictions which have adopted it. Alberta would join Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebéc, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia who have already adopted MI 45-108.

Start-up Business Exemption (Rule 45-517)

As for the new Start-up Business Exemption, here are the essentials as pitched by the ASC:

- Designed for Alberta start-ups seeking to raise funds from Alberta investors

- Aimed at “very modest financing needs”, see the caps below

- Designed to be a simpler and less costly process

- Can be used by issuers wishing to raise funds through their friends and family, or to crowdfund through an online funding portal provided the portal is a registered dealer, and funds are raised only from Alberta investors

- The issuer can issue common shares, non-convertible preference shares, securities convertible into common shares or non-convertible preference shares, among other securities

- Issuer must prepare an offering document

- There is a cap of $250,000 per distribution and a maximum of two start-up business distributions in a calendar year

- Aggregate lifetime cap $1 million

- Designed for a maximum investment amount of $1,500 per investor.  However, through a registered dealer, the maximum subscription from that investor can be as high as $5,000.

- The offering must close within 90 days.

- There is a mandatory 48 hour period for investors to cancel their investment

- The issuer must provide each investor with a specified risk disclosure form and risk acknowledgment form.

Interested in hearing more?

Get in touch with Field Law’s Intellectual Property and Technology Group.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCraft Beer Trademarks (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

Canadians drink a lot of beer.

The number of licensed breweries in Canada has risen 100%  over  the  past  five  years to over 600. In Alberta and B.C. alone, the number of breweries doubled between 2010 and 2015.

Industry trends are shifting, driven by the growth in micro and craft breweries in Canada, a phenomenon mirrored in the U.S., where over 4,000 licensed breweries are vying for the business of consumers, the highest number of breweries in U.S. history.

And with this comes an outpouring of beer-related trademarks.  Brewery names and beer labels invariably lead to the clash of a few beer bottles on the litigation shelf. Let’s have a look at recent U.S. cases:

- The mark ATLAS for beer was contested in the case of Atlas Brewing Company, LLC v. Atlas Brew Works LLC, 2015 TTAB LEXIS 381 (Trademark Trial & App. Bd. (TTAB) Sept. 22, 2015).

- Atlas Brewing Company opposed the trademark application for ATLAS, arguing that there was a likelihood of confusion between ATLAS and ATLAS BREWING COMPANY. The TTAB agreed that there was a likelihood of confusion, since the two marks are virtually identical (the addition of “Brewing Company” is merely descriptive or generic) and the products are identical.

- However, the TTAB ultimately decided that the applicant had earlier rights, since Atlas Brewing Company did not actually sell any products bearing the ATLAS BREWING COMPANY trademark before the filing date for the trademark application. The only evidence related to the pre-sales period – for example, private conversations, letters, and negotiations with architects, builders, and vendors of equipment. The TTAB characterized these as “more or less internal or organizational activities which would not generally be known by the general public”.

- Secondly, there was evidence of social media accounts which used the ATLAS BREWING COMPANY name, but the TTAB was not convinced that this amounted to actual use of the brand as a trademark. “The act of joining Twitter on April 30, 2012, or Facebook on May 14, 2012, does not by itself establish use analogous to trademark use. “

- Interestingly, the TTAB rejected the argument that the beer industry should be treated in a way similar to the pharmaceutical industry: Atlas Brewing Company argued that “there are special circumstances which apply because regulatory approval is required prior to being able to sell beer; and that the beer industry is similar to the pharmaceutical industry, where trademark rights may attach prior to the actual sales of goods, and government approvals are needed prior to actual sales to the general public.” The TTAB countered this by pointing out that pharma companies engaged in actual sales of the product bearing the trademark during the clinical testing phase, prior to introduction into the marketplace. In this case, however, there were no actual sales.

- Thus, the opposition was refused and the application for ATLAS was allowed to proceed.

The old Atlas Brewing Company has since rebranded as Burnt City Brewing, with a knowing wink at the legal headaches: “We’ve all been burned by something, but now we’re back and better than ever.”

Hat tip to Foley Hoag for their round-up of American cases.

Related Reading: How the Craft Brew Boom Is Changing the Industry’s Trademark GameÂ

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentBozo’s Flippity-Flop and Shooting Stars: A cautionary tale about rights management

By Richard Stobbe

If you’ve ever taken piano lessons then titles like “Bozo’s Flippity-Flop”, “Shooting Stars” and “Little Elves and Pixies” may be familiar.

These are among the titles that were drawn into a recent copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the Royal Conservatory against a rival music publisher for publication of a series of musical works. In Royal Conservatory of Music v. Macintosh (Novus Via Music Group Inc.) 2016 FC 929, the Royal Conservatory and its publishing arm Frederick Harris Music sought damages for publication of these works by Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music.

The case serves as a cautionary tale about records and rights management, since much of the confusion between the parties, and indeed within the case itself, could be blamed on missing or incomplete records about who ultimately had the rights to the musical works at issue. In particular, a 1999 agreement which would have clarified the scope of rights, was completely missing. The court ultimately determined that there was no evidence that the defendants Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music could benefit from any rights to publish these songs; the missing 1999 agreement was never assigned or extended to the defendants.

In assessing damages for infringement, the court reviewed the factors set forth in the Copyright Act, including:

- Â the good faith or bad faith of the defendant;

- Â the conduct of the parties before and during the proceedings;

- Â the need to deter other infringements of the copyright in question;

- Â in the case of infringements for non-commercial purposes, the need for an award to be proportionate to the infringements, in consideration of the hardship the award may cause to the defendant, whether the infringement was for private purposes or not, and the impact of the infringements on the plaintiff.

In evaluating the deterrence factor, the court noted: “it is unclear what effect a large damages award would have in deterring further copyright infringement, when the infringement at issue here appears to be the product of poor record-keeping and rights management on the part of both parties.  If anything, this case is instructive that the failure to keep crucial contracts muddies the waters around rights, and any resulting infringement claims. The Respondents should not alone bear the brunt of this laxity, because the Applicants played an equal part in the inability to provide to the Court the key document at issue.” [Italics added]

For these reasons, the court set per work damages at the lowest end of the commercial range ($500 per work), for a total award of $10,500 in damages.

Calgary – o7:00 MST

No commentsProtective Order for Source Code

By Richard Stobbe

A developer’s source code is considered the secret recipe of the software world – the digital equivalent of the famed Coca-Cola recipe. In Google Inc. v. Mutual, 2016 BCSC 1169 (CanLII),  a software developer sought a protective order over source code that was sought in the course of U.S. litigation. First, a bit of background.

This was really part of a broader U.S. patent infringement lawsuit (VideoShare LLC v. Google Inc. and YouTube LLC) between a couple of small-time players in the online video business: YouTube, Google, Vimeo, and VideoShare. In its U.S. complaint, VideoShare alleged that Google, YouTube and Vimeo infringed two of its patents regarding the sharing of streaming videos. Google denied infringement.

One of the defences mounted by Google was that the VideoShare invention was not patentable due to “prior art†– an invention that predated the VideoShare patent filing date.  This “prior art” took the form of an earlier video system, known as the POPcast system.  Mr. Mutual, a B.C. resident, was the developer behind POPcast. To verify whether the POPcast software supported Google’s defence, the parties in the U.S. litigation had to come on a fishing trip to B.C. to compel Mr. Mutual to find and disclose his POPcast source code. The technical term for this is “letters rogatory” which are issued to a Canadian court for the purpose of assisting with U.S. litigation.

Mr. Mutual found the source code in his archives, and sought a protective order to protect the “never-public back end Source Code filesâ€, the disclosure of which would “breach my trade secret rights”.

The B.C. court agreed that the source code should be made available for inspection under the terms of the protective order, which included the following controls. If you are seeking a protective order of this kind, this serves as a useful checklist of reasonable safeguards to consider.

Useful Checklist of Safeguards

- The Source Code shall initially only be made available for inspection and not produced except in accordance with the order;

- The Source Code is to be kept in a secure location at a location chosen by the producing party at its sole discretion;

- There are notice provisions regarding the inspection of the Source Code on the secure computer;

- The producing party is to test the computer and its tools before each scheduled inspection;

- The receiving party, or its counsel or expert, may take notes with respect to the Source Code but may not copy it;

- The receiving party may designate a reasonable number of pages to be produced by the producing party;

- Onerous restrictions on the use of any Source Code which is produced;

- The requirement that certain individuals, including experts and representatives of the parties viewing the Source Code, sign a confidentiality agreement in a form annexed to the order.

A Delaware court has since ruled that VideoShare’s two patents are invalid because they claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsSoftware vendors: Do your employees own your software?

By Richard Stobbe

When an employee claims to own his employer’s software, the analysis will turn to whether that employee was an “author” for the purposes of the Copyright Act, and what the employee “contributed” to the software. This, in turn, raises the question of what constitutes “authorship” of software?  What kinds of contributions are important to the determination of authorship, when it comes to software?

Remember that each copyright-protected work has an author, and the author is considered to be the first owner of copyright. Therefore, the determination of authorship is central to the question of ownership. This interesting question was recently reviewed in the Federal Court decision in Andrews v. McHale and 1625531 Alberta Ltd., 2016 FC 624. Here, Mr. Andrews, an ex-employee claimed to own the flagship software products of the Gemstone Companies, his former employer.  Mr. Andrews went so far as to register copyright in these works in the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.  He then sued his former employer, claiming copyright infringement, among other things.

The former employer defended, claiming that the ex-employee was never an author because his contributions fell far short of what is required to qualify for the purposes of “authorship” under copyright law. The ex-employee argued that he provided the “context and content†by which the software received the data fundamental to its functionality.

The evidence showed that the ex-employee’s involvement with the software included such things as collecting and inputting data; coordination of staff training; assisting with software implementation; making presentations to potential customers and to end-users; collecting feedback from software users; and making suggestions based on user feedback.

The evidence also showed that a software programmer engaged by the employer, Dr. Xu, was the true author of the software. He took suggestions from Mr. Andrews and considered whether to modify the code. Mr. Andrews did not actually author any code, and the court found that none of his contributions amounted to “authorship” for the purposes of copyright.  The court stopped short of deciding that authorship of software requires the writing of actual code; however, the court found that a number of things did not  qualify as “authorship”, including

- collecting and inputting data;

- making suggestions based on user feedback;

- problem-solving related to the software functionality;

- providing ideas for the integration of reports from one software program with another program;

- providing guidance on industry-specific content.

To put it another way, these contributions, without more, did not represent an exercise of skill and judgment of the type of necessary to qualify as authorship of software.

The court concluded that: “It is clearly the case in Canadian copyright law that the author of a work entitled to copyright protection is he or she who exercised the skill and judgment which resulted in the expression of the work in material form.” [para. 85]

In the end, the court sided with the employer. The ex-employee’s claims were dismissed.

Field Law acted as counsel to the successful defendant 1625531 Alberta Ltd.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsOh Canada! … in Trademarks

By Richard Stobbe

In honour of Canada Day tomorrow (for our American readers, that’s the equivalent of Independence Day, with the beer, hotdogs and fireworks, but without the summer blockbuster movie to go along with it), here is our venerable national anthem… in trademarks:

OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey), our HOME AND NATIVE LAND (registered for key chains, mugs, coasters and place mats, but expunged for failure to renew in 2012), TRUE PATRIOT LOVE (registered for accepting and administering charitable contributions to support the Canadian Military and their families) in all our sons command (until the lyrics are amended through a private members bill)! WITH GLOWING HEARTS (abandoned) we see thee rise, the TRUE NORTH (registered for footwear namely shoes, boots, slippers and sandals) STRONG AND FREE (registered for T-shirts, sweaters, and hats)! From far and wide, OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey),  WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee! God keep OUR LAND (registered for fresh fruit), GLORIOUS AND FREE (registered for athletic wear, beachwear, casual wear, golf wear, gym wear, outdoor winter clothing and fridge magnets)! OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey) we stand ON GUARD FOR THEE (registered for travel health insurance services, but abandoned in 1996)! WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee!

Happy Canada Day!

Calgary – 12:00 MST

No comments“Wow Moments” and Industrial Design Infringement

By Richard Stobbe

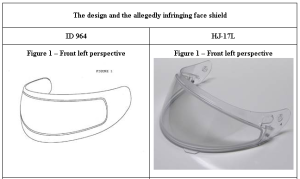

An inventor had a “wow” moment when he came across a design improvement for cold-weather visors – something suitable for the snowmobile helmet market. The helmet maker brought the improved helmet to market and also pursued both patent and industrial design protection. The patent application was ultimately abandoned, but the industrial design registration was issued in 2010 for the “Helmet Face Shield†design, which purports to protect the visor portion of a snowmobile helmet.

AFX Licensing, the owner of the invention, sued a competitor for infringement of the registered industrial design. AFX sought an injunction and damages for infringement under the Industrial Design Act.  The competitor – HJC America – countered with an application to expunge the registration on the basis of invalidity. HJC argued that the design was invalid due to a lack of originality and due to functionality.

Can a snowmobile visor be protected using IP rights?

A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration.

In AFX Licensing Corporation v. HJC America, Inc., 2016 FC 435 (CanLII),  the court decided that AFX’s industrial design registration was valid but was not infringed by the HJC product because the court saw “substantial differences” between the two designs. In summarizing, the court noted the following:

“First, the protection offered by the industrial design regime is different from that of the patent regime…Â the patent regime protects functionality and the design regime protects the aesthetic features of any given product.” (Emphasis added)

The industrial design registration obtained by AFXÂ does “not confer on AFX a monopoly over double-walled anti-fogging face shields in Canada. Rather, it provides a measure of protection for any shield that is substantially similar to that depicted in the ID 964 illustrations, and it cannot be said that the HJ-17L meets that threshold.”

The infringement claim and the expungement counter-claim were both dismissed.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsBREXIT and IP Rights for Canadian Business

By Richard Stobbe

Yesterday UK voters elected to approve a withdrawal from the EU.  What does this mean for Canadian business owners who have intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK?

The first message for Canadian IP rights holders is (in true British style) remain calm and keep a stiff upper lip. All of this is going to take a while to sort out and rights holders will have advance notice of the various means to protect their rights in an orderly fashion. The British are not known for rash actions — ok, other than the Brexit vote.

Rights granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), will be impacted, although the extent of the impact is still to be negotiated and settled. The UK’s membership in WIPO (the World International Property Organisation) is independent of EU membership and so will not be affected by this process. Similarly, the UK’s participation in the European Patent Convention is not dependent on EU membership.

Current speculation is that EU Trade Marks will continue to be recognized as valid in the EU, although such rights will not be recognized in the UK. This may require Canadian rights holders to submit new applications for those marks in the UK, or there may be a negotiated conversion of those EUIPO rights into national UK rights, permitting these registered marks to be recognized both in the EU and the UK.

Copyright law should not be dramatically impacted, since many of the rights of Canadian copyright holders would benefit from international copyright conventions that predate the EU era. However, UK copyright law was undergoing a process to become aligned with EU laws. For example, recent amendments to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were enacted in 2014 to implement EU Directive 2001/29, and the fate of these statutory amendments remains unclear at the moment.

Again, this won’t happen overnight.  Many bureaucrats must debate many regulations before the way forward becomes clear. That’s not much of a rallying cry but it is the reality for an unprecedented event such as this. The good news? If you are a EU IP rights negotiator, you will have steady employment for the next few years.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Series: Words in a foreign language

By Richard Stobbe

A word that clearly describes a particular product or service cannot function as a trademark for that product or service. The Trademarks Act phrases this idea in a more formal way: section 12(1)(b) says that a trade-mark is registrable if it is not … “whether depicted, written or sounded, either clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive in the English or French language of the character or quality of the wares or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used or of the conditions of or the persons employed in their production or of their place of origin”. (Emphasis added)

The case of  Primalda Industries Corp v Morinda, Inc., 2004 CanLII 71759 (CA TMOB), reviewed an application for the trade-mark TAHITIAN NONI Design, for the following wares: “skin care preparations; namely, cleansers, lotions, gels, moisturizing creams” and similar products. The term TAHITIAN NONI refers to the morinda citrifolia tree, which is commonly known as ‘NONI’ in the Polynesian language.  The application was opposed based on a challenge that the mark offended section 12(1)(b) since it was “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive” of the products, by virtue of the fact that the name is a clear description of ingredients in the skin care products, which are derived from the fruit of the ‘Tahitian NONI’ tree.

This might be like trying to register the word CANADIAN MAPLE in association with skin care products derived from, say, the syrup from the maple tree.

However, after reviewing the Act, the court rejected this ground of opposition. Why?

“It is self-evident from the legislation,” the Court said, “that words that might be descriptive in a language other than French or English are not subject to paragraph 12(1)(b). As the opponent alleges in its statement of opposition that ‘NONI’ is a Polynesian word and there is no evidence that it is an English or French word, I conclude that TAHITIAN NONI Design cannot be unregistrable pursuant to paragraph 12(1)(b).”

In short, a clearly descriptive word can be registrable in Canada as long as it is not descriptive in the English of French language.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright and the Creative Commons License

By Richard Stobbe

There are dozens of online photo-sharing platforms. When using such photo-sharing venues, photographers should take care not to make the same mistake as Art Drauglis, who posted a photo to his online account through the photo-sharing site Flickr, and then discovered that it had been published on the cover of someone else’s book. Mr. Drauglis made his photo available through a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which permitted reproduction of his photo, even for commercial purposes.

You might be surprised to find out how much online content is licensed through the “Creative Commons†licensing regime. According to recent estimates, adoption of Creative Commons (CC) has expanded from 140 million licensed works in 2006, to over 1 billion today, including hundreds of millions of images and videos.

In the decision in Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group LLC (U.S. District Court D.C., cv-14-1043, Aug. 18, 2015), the federal court acknowledged that, under the terms of the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, the photo was licensed for commercial use, so long as proper attribution was given according to the technical requirements in the license. The court found that Kappa Map Group complied with the attribution requirements by listing the essential information on the back cover. The publisher’s use of the photo did not exceed the scope of the CC license; the copyright claim was dismissed.

There are several flavours of CC license:

- The Attribution License (known as CC BY)

- The Attribution-ShareAlike License (CC BY-SA)

- The Attribution-NoDerivs License (CC BY-ND)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial License (CC BY-NC)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (CC BY-NC-ND)

- Lastly, a so-called Public Domain (CC0) designation permits the owner of a work to make it available with “No Rights Reservedâ€, essentially waiving all copyright claims.

Looks confusing? Even within these categories, there are variations and iterations. For example, there is a version 1.0, all the way up to version 4.0 of each license. The licenses are also translated into multiple languages.

Remember: “available on the internet†is not the same as “free for the takingâ€. Get advice on the use of content which is made available under any Creative Commons license.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsAndroid vs. Java: Copyright Update

By Richard Stobbe

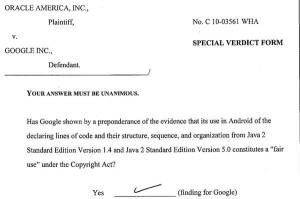

In a sprawling,  billion-dollar lawsuit that started in 2010, a jury yesterday returned a verdict in favour of Google, delivering a blow to Oracle.  (For those who have lost the thread of this story, see : API Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round).

The essence of Oracle America Inc. v. Google Inc. is a claim by Oracle that Google’s Android operating system copied a number of APIs from Oracle’s Java code, and this copying constituted copyright infringement. Infringement, Oracle argued, that should give rise to damages based on Google’s use of Android. Now think for a minute of the profits that Google might attribute to its use of Android, which has dominated mobile operating system since its introduction in 2007. Oracle claimed damages of almost $10 billion.

In prior decisions, the US Federal Court decided that Google’s copying did infringe Oracle’s copyright. The central issue in this phase was whether Google could sustain a ‘fair use’ defense to that infringement. Yesterday, the jury sided with Google, deciding that Google’s use of the copied code constituted ‘fair use’, effectively quashing Oracle’s damages claim.

Oracle reportedly vowed to appeal.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments