BEER BEER as a trademark… for “beerâ€?

By Richard Stobbe

There is a rule in Canadian trademarks law that you can’t get a trademark for a word that describes the product you’re selling. Makes sense, right? No-one should have a monopoly over a word that is descriptive of the thing they’re selling. Such a term should be open to everyone to use.

Drummond Brewing applied to register BEER BEER as a trademark for “beerâ€.  Wait, let’s re-read the paragraph above. Isn’t BEER BEER clearly descriptive when used in association with the sale of beer?  Drummond, apparently, did not think so when it filed its application claiming use since 2009. They held this opinion despite an earlier decision (Coors Global Properties, Inc. v. Drummond Brewing Company, 2011 TMOB 44 (March 11, 2011)) which found BEER BEER to be clearly descriptive.

There is well-known decision from the early 1980s (Pizza Pizza Ltd. v. Registrar of Trade Marks (1982), 67 C.P.R. (2d) 202), where the court decided that the mark PIZZA PIZZA was found not to be clearly descriptive of “pizza†since the expression PIZZA PIZZA was not a linguistic construction that is a part of normally acceptable spoken or written English. If it works for pizza, why not beer?

In the decision Molson Canada 2005 v Drummond Brewing Company Ltd., 2017 TMOB 78 (CanLII),  Molson opposed this trademark, and Drummond fought back, insisting that the mark was not descriptive. Numerous experts from both sides weighed in on the meaning of the term BEER BEER as a linguistic construction. One expert provided an opinion as a sociolinguist after  consulting scholarly literature, fellow linguists, and the Corpus of English Contrastive Focus Reduplications, a collection of 203 examples of naturally occurring utterances featuring contrastive reduplicative constructions, as published in the scholarly journal Natural language and Linguistic Theory (NLLT), 2004.

I’m not making this stuff up.

In the end, common-sense prevailed and the decision-maker found that the mark BEER BEER was clearly descriptive of the product. The mark was found to be unregistrable as a trademark.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Google vs. Equustek: Google Loses Another Round

By Richard Stobbe

How far can Canadian courts reach when making orders that seek to control the conduct of foreign companies outside of Canada? This controversial question is still being decided, bit by bit, in both Canadian and US courts. In our past posts we have written about a 2014 pre-trial temporary court order that required Google to de-index certain sites from Google’s worldwide search results, based on an underlying lawsuit that the plaintiff, Equustek, brought against the defendants back in 2011.  Google challenged the order requiring it to delist worldwide search results, and fought this order all the way up to the Supreme Court of Canada… where Google lost.

On July 24, 2017, approximately one month after the SCC decision, Google filed a complaint in US Federal Court, seeking an order that the injunction issued by the BC court is unlawful and unenforceable in the United States. That order was granted, first on a preliminary application on November 2, 2017 and then in a final ruling on December 14, 2017. With that US court decision in hand, Google came back to the BC court which had issued the original order, to vary the scope of that order.

On April 16, 2018, in Equustek Solutions Inc. v Jack, 2018 BCSC 610 (CanLII), the BC court again rejected Google’s requests. The BC court said that the US decision (which was in Google’s favour) did not establish that the injunction requires Google to violate American law. And without any significant change in circumstances, the court reasoned, there was no reason to change the original order. As a result, the temporary order against Google – which has been in place since 2014 – remains in place, pending outcome of the trial.

The outcome of that trial will be closely watched. As I mentioned in my earlier article, there has been very little analysis of Equustek’s IP rights by any of the different levels of court. Since this entire case involved pre-trial remedies, the merits of the underlying allegations and the strength of Equustek’s IP rights have never been tested at trial. In order for the injunction to make sense, one must assume that the IP rights were valid. Even if they are valid, it is questionable whether Equustek’s rights are worldwide in nature since there was no evidence of any worldwide patent rights or international trademark portfolio. We can only hope that the trial decision, and Google’s decision to appeal the latest BC court decision, will clarify these issues.

Calgary – 07:00 MDT

No commentsArtist Sues for Infringement of “Moral Rights”

By Richard Stobbe

AÂ professional photographer sued the gallery that sold his works, and won a damage award for copyright infringement, infringement of moral rights, and punitive damages. In this case (Collett v. Northland Art Company Canada Inc., 2018 FC 269 (CanLII)), Mr. Collett, the photographer, alleged that his former gallery, Northland, infringed his rights after their business relationship broke down.

We don’t see many “moral rights” infringement cases in Canada, so this case is of interest for artists and other copyright holders for this reason alone. What are “moral rights”?

In Canada the Copyright Act tells us that the author of a work has certain rights to the integrity of the work, the right to be associated with the work as its author by name or under a pseudonym and the right to remain anonymous.

These so-called moral rights of the author to the integrity of a work can be infringed where the work is “distorted, mutilated or otherwise modified” ina way that compromises or prejudices the author’s honour or reputation, or where the work is used in association with a product, service, cause or institution that harms the authors reputation. Determining infringement has a highly subjective aspect, which must be established by the author. But this type of claim also has an objective element requiring a court to evaluate the prejudice or harm to the author’s “honour or reputation” which can be supported by public or expert opinion.

Here, the court found that the gallery had infringed Mr. Collett’s moral rights when the gallery intentionally reproduced one print entitled “Spirit of Our Land†and attributed the work to another artist. By reproducing “Spirit of Our Land†without Mr. Collett’s permission, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in the work. By attributing the reproductions to another artist, the gallery infringed the artist’s moral right “to be associated with the work as its authorâ€. This is actually a useful illustration of the difference between these different types of artist’s rights.

The unauthorized reproductions sold by the gallery were apparently taken from a copy resulting in images of lower resolution and therefore inferior quality, compared to authorized prints; unfortunately, we don’t have any insight into whether inferior quality would also infringed the artist’s moral right to the integrity of the work. The court declined to comment on this aspect since it had already concluded that moral rights were infringed when the prints were sold under the name of another artist.

Lastly, and interestingly, the court found that a link from the gallery’s site to the artist’s website constituted an infringement of copyright. It’s difficult to see how a link, without more, could constitute a reproduction of a work, unless the linked site was somehow framed or otherwise replicated within the gallery’s site. The evidence is not clear from reading the decision but the artist’s allegation was that the gallery “reproduced the entirety” of certain pages from the artist’s site, which created the false impression that the gallery still represented the artist. The court noted that the gallery continued to maintain a link to Mr. Collett’s website “knowing it was not authorized to do so.” By doing so, the gallery infringed the artist’s copyright in his site, including a reproduction of certain prints. Maintaining such a link was not found to constitute a breach of the artist’s moral rights.

In the end, statutory damages of $45,000 were awarded for breach of copyright, $10,000 for infringement of moral rights, and $25,000 for punitive damages to punish the gallery for its planned, deliberate and ongoing acts of infringement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCanadian Beer Trademarks: When is a moose just a moose?

HEAD OF MOOSE DESIGN

By Richard Stobbe

When is a moose just a moose?

Apparently when it is reclined in a parlour sipping gin.

In Moosehead Breweries Limited v Eau Claire Distillery Ltd., 2018 TMOB 24 (CanLII), Canadian brewer Moosehead Breweries, the oldest, privately owned, independent brewery in Canada complained about confusion based on its well-known moose marks for beer (including Registration number TMA667312, as shown above).

Moosehead alleged that the PARLOUR GIN DESIGN for gin (Application No. 1,667,113) owned by Alberta’s own Eau Claire Distillery Ltd., was confusing with Moosehead’s own moose marks for beer.  In Eau Claire’s mark, an anthropomorphic moose character and anthropomorphic bear character are seated in formal clothing amidst Victorian parlour furnishings, sipping gin and engaging in polite conversation. Does the use of the moose for gin make this mark confusing with Moosehead’s brand for beer?

Canadian courts tell us that the test for confusion is “a matter of first impression in the mind of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry who sees the [mark], at a time when he or she has no more than an imperfect recollection of the [prior] trade-marks, and does not give pause to give the matter any detailed consideration or scrutiny, nor to examine closely the similarities and differences between the marks.”

In this case, the decision-maker dismissed Moosehead’s opposition, after going through the factors, namely: (a) the inherent distinctiveness of the trade-marks and the extent to which they have become known; (b) the length of time each has been in use; (c) the nature of the goods, services or business; (d) the nature of the trade; and (e) the degree of resemblance between the trade-marks in appearance or sound or in the ideas suggested by them. There is no reasonable likelihood of confusion since the marks bear little resemblance in appearance, sound, and in the ideas suggested by them.

Moosehead’s challenge was rejected, and the Eau Claire mark will proceed.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsFacebook at the Supreme Court of Canada: forum selection clause is unenforceable

By Richard Stobbe

We just wrote about a dispute resolution clause that was enforceable in the Uber case. Last year, a privacy class action claim landed in the Supreme Curt of Canada (SCC) and I see that we haven’t had a chance to write this one up yet.

In our earlier post ( Facebook Follows Google to the SCC  ) we provided some of the background: The plaintiff Ms. Douez alleged that Facebook used the names and likenesses of Facebook customers for advertising through so-called “Sponsored Storiesâ€. The claim alleged that Facebook ran the “Sponsored Stories†program without the permission of customers, contrary to of s. 3(2) of the B.C. Privacy Act. The basic question was whether Facebook’s terms (which apply California law) should be enforced in Canada or whether they should give way to local B.C. law. The lower court accepted that, on its face, the Terms of Service were valid, clear and enforceable and the lower court went on to decide that Facebook’s Forum Selection Clause should be set aside in this case, and the claim should proceed in a B.C. court. Facebook appealed that decision: Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2015 BCCA 279 (CanLII) (See this link to the Court of Appeal decision). The appeal court reversed and decided that the Forum Selection Clause should be enforced. Then the case went up to the SCC.

In Douez v. Facebook, Inc., [2017] 1 SCR 751, 2017 SCC 33 (CanLII), the SCC found that Facebook’s forum selection clause is unenforceable.

How did the court get to this decision?  Um…. hard to say, even for the SCC itself, since there was a 3-1-3 split in the 7 member court, with some judges agreeing on the result, but using different reasoning, making it tricky to find a clear line of legal reasoning to follow. The court endorsed its own “strong cause” test from Z.I. Pompey Industrie v. ECU-Line N.V., 2003 SCC 27 (CanLII): When parties agree to a jurisdiction for the resolution of disputes, courts will give effect to that agreement, unless the claimant establishes strong cause for not doing so. Here, the Court tells us that public policy considerations must be weighed when applying the “strong cause” test to forum selection clauses in the consumer context. The public policy factors appear to be as follows:

- Are we dealing with a consumer contract of adhesion between an individual consumer and a large corporation?

- Is there a “gross inequality of bargaining power” between the parties?

- Is there a statutory cause of action, implicating the quasi-constitutional privacy rights? These constitutional and quasi-constitutional rights play an essential role in a free and democratic society and embody key Canadian values, so this will influence the court’s analysis.

- The court will also assess “the interests of justice” and decide which court is better positioned to assess the purpose and intent of the legislation at issue (as in this case, where there was a statutory cause of action under the BC Privacy Act).

- Lastly, the court will assess the expense and inconvenience of requiring an individual consumer to litigate in a foreign jurisdiction (California, in this case), compared to the comparative expense and inconvenience to the big bad corporation (Facebook, in this case).

The court noted that, in order to become a user of Facebook, a consumer “must accept all the terms stipulated in the terms of use, including the forum selection clause. No bargaining, no choice, no adjustments.” But wait… Facebook is not a mandatory service, is it? The fact that a consumer’s decision to use Facebook is entirely voluntary seems to be missing from the majority’s analysis. A consumer must accept the terms, yes, but there is a clear choice: don’t become a user of Facebook. That option does not appear to be a factor in the court’s analysis.

The take-home lesson is that forum selection clauses will have to be carefully handled in consumer contracts of adhesion. It is possible that this decision will be limited to these unique circumstances.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 3)

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1 and Part 2, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

In the final part, we review the next couple of areas:

- Copyright

Copyright is a very flexible and wide-ranging tool to use in the fashion and apparel industry.  Under the Copyright Act, a business can use copyright to protect original expression in a range of products including artistic works, fabric designs, two and three-dimensional forms, and promotional materials, such as photographs, advertisements, audio and video content. For example, in Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. et al. and Singga Enterprises (Canada) Inc., the Federal Court sent a strong message to counterfeiters. This was a case of infringement of copyright , arising from the sale of counterfeit copies of Louis Vuitton and Burberry handbags through online sales and operations in Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton. Louis Vuitton owns copyright in the following Multicolored Monogram Print pattern:

Since the Copyright Act provides for an award of both damages and profits from the sale of infringing goods, or statutory damages between $500 to $20,000 per infringed work, the copyright owner had a range of options available to enforce its IP rights. In this case, the Federal Court awarded Louis Vuitton and Burberry a total of over $2.4 million in damages against the defendants, catching both the corporate and personal defendants in the award.

- Personality Rights

In Canada, the use of a famous person’s personality for commercial gain without authorization can lead to liability for “misappropriation of personalityâ€. To establish a case of misappropriation of personality, three elements must be shown:

- The exploitation of personality is for a commercial purpose.

- The person in question is identifiable in the context; and

- The use of personality suggests some endorsement or approval by the person in question.

Just ask William Shatner who objected on Twitter when his name and caricature were used to promote a condo development in Ontario, in a way that suggested that he endorsed the project.

Canadian personality rights benefit from some protection at the federal level through the Trademarks Act and the Competition Act, and are protected in some provinces. B.C., Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec have privacy statutes that restrict the unauthorized commercial use of personality, although the various provincial statutes approach the issue slightly differently. Specific advice is required in different jurisdictions, depending on the circumstances.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsGoogle vs. Equustek Saga: The Final Countdown

By Richard Stobbe

Last month we asked: The Google vs. Equustek Decision: What comes next?

Part of the answer was handed down recently by a B.C. court in Equustek Solutions Inc. v Jack, 2018 BCSC 329 (CanLII), after Google applied to vacate or vary the original order of Madam Justice Fenlon, which was granted way back in 2014. That was the order that set off a furious international debate about the reach of Canadian courts, since it required Google to de-index certain sites from Google’s worldwide search results, based on an underlying lawsuit that the plaintiff Equustek brought against the defendants (which is finally set for trial in April, 2018).

Google of course was always invited to seek a variation of that original court order. As noted by the latest judgment, that right to apply to vary has been recognized by the B.C. Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada. After Google received a favourable decision last year from a US court, the way was paved to vary the original order that has caused Google so much heartburn. The next step is that Google will seek a cancellation or limitation of the scope of that original order, so that the order applies only to search results in Canada through google.ca.

The last step, with luck, will be a hearing of the merits of the underlying IP claims; some commentators have questioned why Google was used to obtain a practical worldwide remedy when the IP rights asserted by Equustek do not appear to be global in scope. As I mentioned in my earlier article, there has been very little analysis of Equustek’s IP rights by any of the different levels of court. Since this entire case involved pre-trial remedies, the merits of the underlying allegations and the strength of Equustek’s IP rights have never been tested at trial. In order for the injunction to make sense, one must assume that the IP rights were valid. Even if they are valid, Equustek’s rights couldn’t possibly be worldwide in nature. There was no evidence of any worldwide patent rights or international trademark portfolio. So, the court somehow skipped from “the internet is borderless†to “the infringed rights are borderless†and are deserving of a worldwide remedy.

To be continued…

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Uber vs. Drivers: Canadian Court Upholds App Terms

.

By Richard Stobbe

One of Uber’s drivers, an Ontario resident named David Heller, sued Uber under a class action claim seeking $400 million in damages. What did poor Uber do to deserve this? According to the claim, drivers should be considered employees of Uber and entitled to the benefits of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act (See: Heller v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2018 ONSC 718 (CanLII)).

As the court phrased it, while “millions of businesses and persons use Uber’s software Apps, there is a fierce debate about whether the users are customers, independent contractors, or employees.” If all of the drivers are to be treated as employees, the costs to Uber would skyrocket. Uber, of course, resisted this lawsuit, arguing that according to the app terms of service, the drivers actually enter into an agreement with Uber B.V., an entity incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands. By clicking or tapping “I agree” in the app terms of service, the drivers also accept a certain dispute resolution clause: by contract, the parties pick arbitration in Amsterdam to resolve any disputes.

Really, at this stage Uber’s defence was not to say “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers are independent contractors, not employees”. Rather, Uber argued that “this claim should not proceed because all of the drivers agreed to settle disputes with us by arbitration in the Netherlands.”

So the court had to wrestle with this question:  Should the dispute resolution clause in the click-through terms be upheld? Or should the drivers be entitled to have their day in court in Canada?Â

The law in this area is very interesting and frankly, a bit muddled. This is because there are two distinct issues in this legal thicket: a forum-selection clause (the laws of the Netherlands govern any interpretation of the agreement), and a dispute resolution clause (here, arbitration is the parties’ chosen method to resolve any disputes under the agreement). For these two different issues, Canadian courts have applied different tests to determine whether such clauses should be upheld:

- In the case of forum selection clause, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) tells us that the rule from Z.I. Pompey Industries is that a forum selection clause should be enforced unless there is “strong cause†not to enforce it.  In the context of a consumer contract (as opposed to a “commercial agreement”), the SCC says there may be strong reasons to refrain from enforcing a forum selection clause (such as unequal bargaining power between the parties, the convenience and expense of litigation in another jurisdiction, public policy reasons, and the interests of justice). In the commercial context (as opposed to a consumer agreement), forum selection clauses are generally upheld.

- In the case of upholding arbitration clauses, the courts have applied a different analysis: arbitration is generally favoured as a means to settle disputes, using the “competence-competence principle”. Again, it’s an SCC decision that gives us guidance on this: unless there is clear legislative language to the contrary, or the dispute falls outside the scope of the arbitration agreement, courts must enforce arbitration agreements.

The court said this case “is not about a discretionary court jurisdiction where there is a forum selection clause to refuse to stay proceedings where a strong cause might justify refusing a stay; rather, it is about a very strong legislative direction under the Arbitration Act, 1991 or the International Commercial Arbitration Act, 2017 and numerous cases that hold that courts should only refuse a reference to arbitration if it is clear that the dispute falls outside the arbitration agreement.”

Applying the competence-competence analysis, the court (in my view) properly ruled in favour of Uber, upheld the app terms of service, and deferred this dispute to the arbitrator in the Netherlands. This class action, as a result, must hit the brakes.

The decision is reportedly under appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentCopyright in Architectural Works: an update

By Richard Stobbe

Who owns the copyright in a building?  A few years ago, we looked at the issue of Copyright in House Plans, but let’s look at something bigger. Much bigger.

In Lainco inc. c. Commission scolaire des Bois-Francs, 2017 CF 825, the federal court reviewed a claim by an architectural engineering firm over infringement of copyright in the design for an indoor soccer stadium.

Lainco, the original engineers, sued a school board, an engineering firm, a general contractor and an architect, claiming that this group copied the unique design of Lainco’s indoor soccer complex. The nearly identical copycat structure built in neighbouring Victoriaville was considered by the court to be an infringement of the original Lainco design even though the copying covered functional elements of the structure. The court decided that such functional structures can be protected as “architectural works†under the Copyright Act, provided they comprise original expression, based on the talent and judgment of the author, and incorporate an architectural or aesthetic element.

The group of defendants were jointly and severally liable for the infringement damage award, which was assessed at over $700,000.

Make sure you clarify ownership of copyright in architectural designs with counsel to avoid these pitfalls.

Calgary – 07:00

No comments

IP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 2, let’s review the next couple of areas:

- Industrial Design or “Design Patentâ€:

I always tell my clients not to underestimate this lesser-known area of IP protection. It can be a very powerful tool in the IP toolbox. In both Canada (which uses the term industrial design) and the US (which refers to a design patent), this category of intellectual property only provides protection for ornamental aspects of the design of a product as long as they are not purely functional . To put this another way, features that are dictated solely by a utilitarian function of the article are ineligible for protection.

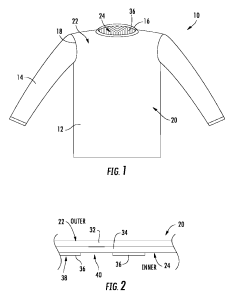

Registration is required and protection expires after 10 years. A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration. Some examples:  This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

The solid lines on the image above represents a protected design registration filed by Nike.

TIP: Placement of a pocket on a t-shirt may not be considered innovative, but even minor differentiators can help distinguish a product in a crowded field. A design registration can support a blended strategy which also deploys other IP protection, such as trademark rights.

- Trademarks:

Every consumer will be intuitively familiar with the power of a brand name such as LULULEMON or NIKE, or the well-known Nike Swoosh Design. That topic is well-covered elsewhere. However, some brands take advantage of a lesser-known area of trademark rights: distinguishing guise protects the shape of the product or its packaging. It differs from industrial design, and one way to consider the distinction is that an industrial design protects new ornamental features of a product from when it is first used, whereas a distinguishing guise can be registered once it has been used in Canada so long that becomes a brand, distinctive of a manufacturer due to extensive use of the mark in the marketplace. It’s worth noting that the in-coming amendments to the Trademarks Act will do away with distinguishing guises.

One good example is the well-known shape of CROCS-brand sandals. The shape and appearance of the footwear itself has been used so long that it now functions as a brand to distinguish CROCS from other sandals. Just as with industrial design, the protected features cannot be dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.

Others have filed distinguishing guise registrations in Canada, including Canada Goose Inc. for coats and Hermès International for handbags.

TIP: For a distinguishing guise application, each applicant will have to file evidence to show that the mark is distinctive in the marketplace in Canada. That is not the case with a regular trademark, such a word mark or regular logo design.

We review the final areas of IP protection in Part 3.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Evolution: Part 2 (When Technology Changes)

By Richard Stobbe

Technology certainly evolves. Can a trademark evolve? In the world of intellectual property rights, a registered trademark can live on for a hundred years or more. If you registered a trademark in the 1800s, it could still be valid today. But will the underlying product be delivered to customers the same way? (See: Goodbye Floppy Disk, Hello Streaming Video: Trademark Evolution, Part 2).

- In the 1980s Canadian courts recognized that service delivery can evolve in the decision in BMB Compuscience Canada Ltd v Bramalea Ltd. (1988), 22 CPR (3d) 561 (FCTD). In that case, BMB applied to register the mark NETMAIL in association with a computer program. But the NETMAIL product was not sold as a physical object, and courts have recognized that software vendors can experience “unique difficulties†when attempting to associate a trade-mark with its software, since there is no label, packaging or hang-tag, as with other types of goods. The court in BMB Compuscience was prepared to take a flexible approach and permit a software vendor like BMB to demonstrate “use†of its mark for the purposes of the Trade-marks Act where the brand was shown on a computer screen during product demonstrations.

- This concept was more recently applied in Davis LLP vs. 819805 Alberta Ltd., 2016 TMOB 64, a Section 45 challenge to the registered trademark BIBLIOTECA. The mark BIBLIOTECA was registered in association with certain software “goodsâ€. The goods were described as “Computer software, namely a computer database containing information for use in the field of building design and construction.â€Â During the relevant period, the database was accessed by customers as part of an online service, without the sale of any tangible or physical product. The BIBLIOTECA decision adopted the reasoning in BMB Compuscience to allow the trademark owner to demonstrate “use†of the mark in ways that reflected technological changes in the way this product was delivered to customers.

- In the United States, the USPTO is running a pilot program to allow amendments to identifications of goods and services in trademark registrations due to changes in technology, including many cases where floppy disks and cartridges are being updated to reflect online streaming. For example, the mark PHOTODISC, owned by Getty Images, was originally registered in association with stock photography “contained in digital format on CD-ROMs.â€Â Through the amendment process, Getty Images is proposing an amendment to reflect the changes in how its stock photo products are delivered: “in digital format on electronic or computer media or downloadable from databases or other facilities provided over global computer networks, wide area networks, local area networks, or wireless networks…â€

- Perhaps the best reflection of this is the US registered mark for THE MARCH OF TIME, used in association with newsreels and originally registered in 1935. Embedded in the original trademark application is a description of the technological breakthrough of allowing motion pictures to be broadcast with sound: “motion picture films for use in connection with synchronized apparatus for simultaneously reproducing coordinated light and sound effect.â€Sadly, this piece of history is now being replaced with the bland description “Providing non-downloadable online videos featuring historical newsreel.†I guess that evokes the march of time !

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 1)

.

By Richard Stobbe

Complex technology like blockchain is in fashion. What about IP protection for seemingly simple items like shirts, shoes and undergarments? As competitors jostle for position in the fashion and apparel marketplace, how do intellectual property rights apply? Make no mistake, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patent”

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 1, let’s review the first two areas:

- Confidential Information

Confidential information or ‘trade secrets’ refers simply to information that has value to a designer or manufacturer because competitors don’t have access to the information. As long as the information is kept secret, and is only disclosed to others in confidence, then the secrets may remain protected as ‘trade secrets’ for many years. The confidential information may be made up of related business information, such as contacts of suppliers, pricing margins, new product ideas or prototype designs. The period of confidentiality may be short-lived in the case of a new product design: once the product is released to customers, it’s no longer confidential.

An owner of confidential information must take steps to maintain confidentiality, and the information should only be disclosed under strict terms of confidentiality (as part of a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), or confidentiality agreement).

If the confidential information is misappropriated, the owner can seek to enforce its rights by proving that the information has the required quality of confidentiality, the information was disclosed in confidence, and there was an unauthorized use or disclosure in a way that caused harm to the owner.

TIP: Ensure that you take practical steps to limit access to the confidential info. And when signing an NDA, make sure it doesn’t contain any terms that might inadvertently compromise confidentiality or give away IP rights.

- Patents

Many apparel and footwear companies rely heavily on patent protection to block competitors and gain an advantage in the marketplace.

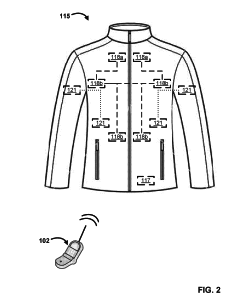

Let’s take a few examples. In pursuing the ‘holy grail’ of outdoor activewear, many manufacturers are seeking a comfortable, breathable jacket that can keep a wearer warm without overheating. The North Face System recently filed an application for a smart-sensing jacket using sensors to determine a “comfort signature” based on differences in environmental conditions between the sensors and making adjustments for the wearer.

A competitor – Under Armour Inc. – is seeking patent protection for garments incorporating printed ceramic materials to retain heat, without sacrificing other performance qualities such as  water and dirt repellency, durability, breathability and moisture-wicking qualities. In this patent application, Under Armour is seeking protection not only for the fabric but also the innovative method of manufacturing the fabric.

From high-tech jackets to innovative shoe designs, to more specific components, such as garment linings, or improved fasteners, patents can provide a valuable tool to ensure that a company’s research-and-development initiatives can bear fruit in the marketplace. By providing a period of exclusivity for the patent holder, this category of IP protection keeps the field clear of infringing replicas while the company recoups its investments and turns a profit on a successful product technology.

In the case of many fashion or apparel products, the time and cost of patent protection – it may take several years before a valid patent is issued – may not be justified in light of the high turn-over in seasonal product lines, and the ever-shifting tastes of consumers.

TIP: Make sure you consider both sides of the patent issue: as an inventor, an investment in patent protection may be worth considering, particularly in a product area where the underlying ‘technology’ or innovation may be commercialized over a number of years, such as the famous Gore-Tex fabric, even though superficial fashions may change during that time. On the flip side, manufacturers should take care to ensure that their own designs are not infringing the patent rights of some other patent holder.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 commentsThe Blockchain Patent Gold Rush

By Richard Stobbe

The blockchain technology underlying BitCoin and other cryptocurrencies was originally designed and conceived as an open protocol that would not be owned by any one centralized entity, whether government or private. Just like other foundational protocols that were created in the early days of the internet (email is based on POP, SMTP and IMAP, and websites rely on HTTP, and file transfers use FTP and TCP/IP), no-one really owns these protocols.  No-one collects royalties or patent licensing fees for the use of these protocols (…though some patent assertion entities might argue otherwise).

Similarly, the peer-to-peer vision underlying “the blockchain” was conceptually directed to maintaining the integrity of peer-to-peer transactions that function outside the realm of a centralized overseer such as a bank or government registry. Where, traditionally, a bank served as the trusted and verifiable record of a transaction, the use of blockchain technology could provide an alternative trusted and verifiable record of a transaction. No bank required.

It should come as no surprise, then, that banks are rushing to own a piece of this space.

A recent U.S. report shows: “The financial industry dominates the list of the top ten blockchain-related patent holders. … Leading the list is Bank of America with 43 patents, MasterCard International with 27 patents, FMR LLC (Fidelity) with 14 patents, and TD Bank with 11 patents. Other major financial institutions with blockchain patents include Visa Inc. with 7 patents, American Express with 6 patents, and Nasdaq Inc. with 5 patents.” (Blockchain Patent Filings Dominated by Financial Services Industry, Posted on January 12, 2018Â

Will the privatization of blockchain technologies spur adoption of this technology in the business-to-business layer? Or will the patent gold rush merely erect proprietary fences in a way that constrains adoption?

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Craft Beer Branding

By Richard Stobbe

In one of the more absurd episodes of bureaucratic overreach, craft brewer Stalwart Brewing Company ran into a regulatory headache when the LCBO raised concerns about the regulatory prohibition on health claims related to Stalwart’s label for ” Dr. Feelgood India Pale Ale”.

The regulator’s complaint was that the label – featuring a tongue-in-cheek portrayal of a snake wrapped around a mash-paddle-medieval-sword, mimicking a Rod of Asclepius – was somehow crossing the line by making unsubstantiated medical claims…Because apparently Canadian beer consumers wouldn’t be able to decipher that “Dr. Feelgood” is not a real physician, and might think that the IPA contained in the can was real medicine.

Leaving aside the thorny question of whether IPA qualifies as medicine, the branding and trademark issues arises in a number of ways:

- Trademark  searches can clear a proposed brand as against other similar marks which may be registered or pending for similar products;

- Trademark searches can be done in conjunction with the process of meeting federal and provincial labelling requirements;

- This case is a reminder that trademark preclearance must also take into account other rules, such as:

- alcohol by volume declarations;

- the correct naming for “low alcohol beer” vs. “light beer” vs. “extra strong beer”;

- “Lager” on its own is not an acceptable common name for beer. The common name “beer” must be listed in addition to the description “lager”;

- naming conventions related to gluten-free beer.

On a positive note, the original Dr. Feelgood cans should now be a collector’s item.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsA Software Vendor and its Customer: “like ships passing on a foggy nightâ€

By Richard Stobbe

When a customer got into a dispute with the software vendor about the license fees, the resulting case reads like a cautionary tale about software licensing. In ProPurchaser.com Inc. v. Wifidelity Inc., 2017 ONSC 7307 (CanLII), the court reviewed a dispute about a Software License Agreement. The customer, ProPurchaser, signed a license agreement with Wifidelity for the license of certain custom software at a rate of $6,000 per month. Over time, this fee increased and at the time the dispute commenced in 2017, ProPurchaser was paying a monthly fee of about $42,000.  The customer paid this fee, but apparently had no way of telling what it was paying for.

Detailed invoices were never submitted and so it was impossible to tell objectively how this fee should be broken down between license fees, support fees, expenses, or commissions.  The customer had formed the impression that this increase was due to support fees at an hourly rate, since the original license of $6,000 per month remained in effect and had never been amended in writing.

The software vendor, on the other hand, gave evidence that the license fee had increased under a verbal agreement between the parties.  “Based on the conflicting evidence,†the court mused, “it seems that the parties, much like ships passing on a foggy night, proceeded for several years unaware of the other’s different understanding about what was being charged by Wifidelity and paid for by ProPurchaser.â€

Under the Software License, either party was entitled to terminate without cause, by providing 14 days’ written notice to the other party. Eventually, the software vendor, Wifidelity, exercised the right of termination, triggering the lawsuit. ProPurchaser immediately sought a court order preserving the status quo, to prevent the software vendor from shutting down the software. In August, the court granted that order for a period of six months, subject to continuing payment of the $42,000 monthly license fee by ProPurchaser.  In November, ProPurchaser again approached the court, this time for an order extending the order until trial. Such an order could, in effect, be tantamount to a final resolution of the dispute, forcing the license to remain in effect. However, this would fly in the face of the clear terms of the agreement, which permitted for termination on 14 days’ notice.

While the dispute has yet to go to trial, there are some interesting lessons for software vendors and licensees:

- From a legal perspective, in order to succeed in its injunction application, ProPurchaser had to convince the court that termination of the license caused “irreparable harmâ€. However, the agreement itself allowed each party to terminate for no reason on very short notice, making it difficult to argue that this outcome – one that both sides had agreed to – would cause harm. If it caused so much harm, why did ProPurchaser agree to it in the first place? And in any event, any harm was compensable in damages and therefore not “irreparableâ€.

- That was a problem for the customer, when making a fairly narrow legal argument, but it’s also a problem from a business perspective. If the licensed software supports mission-critical functions within the licensee’s business, then make sure it’s not terminable for convenience by the software vendor.

- If changes are made to the software license agreement, particularly regarding the essential business terms like license fees and support fees, make sure these amendments are captured in writing, through a revised pricing schedule, or detailed invoicing that has been accepted by both sides.

Calgary – 13:00Â MST

No comments

Trademark Evolution: Part 1 (When Trademarks Change)

By Richard Stobbe

The famous Toblerone bar is so distinctive in shape and design that it serves as a great example of a “distinguishing guise†trademark. It has been used as a  trademark since 1910 in Canada, and during that time has maintained the same “tread design†of chocolate peaks, which has been a registered trademark in Canada since 1969.

It’s the actual shape of the bar that functions as a trademark. The bar is really a whole trademark treasure-trove since the unique shape of the triangular box, the colour scheme of the lettering, and the word TOBLERONE, are all separate trademarks, registered in a number of countries around the world.

The Swiss chocolatier redesigned the famous bar for the UK marketplace (reportedly in response to price adjustments required in the wake of Brexit). The newly redesigned bar expanded the valleys, resulting in fewer peaks, all to shave costs.  This of course resulted in a minor scandal in the UK, as well as some heartburn for the company’s trademark counsel.

If the mark-as-used departs from the mark-as-registered, there is a risk that the original registered mark has been abandoned, putting the strength of the registered rights at risk. This is a basic tenet of trademark law. While minor changes are permitted as a brand evolves, there is a point at which the changes go too far, essentially resulting in the adoption of a new mark.

Seeing this vulnerability, a competitor entered the marketplace with a bar “inspired by†the original Toblerone bar. Poundland, a UK discount retailer, introduced a double-peaked chocolate bar complete with knock-off packaging that mimics the distinctive gold background and red lettering of the original Toberlone package.

After a legal wrangle that reportedly kept the Poundland product off store shelves for several months, the dispute was settled and Poundland introduced modified packaging, featuring gold lettering against a blue background.

The lessons for business?

- In the field of consumer products, this is a good reminder that the shape of the product or its packaging can serve as a trademark, and can be registered as a means of  protecting brand rights.

- When a product or trademark evolves over time – whether in response to cost pressures, as in the Toblerone case, or in response to changes in the marketplace, or consumer demands – it’s important to measure the modified mark against the original mark, as it was registered. If the departure is too great, the rights to the original mark may be placed at risk.

Calgary – 09:00 MST

No commentsPrivacy Breach … While Jogging Down a Public Path?

.

By Richard Stobbe

An online video shows someone jogging on a public pathway during a 2-second clip. Let me get this straight… does this constitute a breach of privacy rights? According to an Ontario court, the answer is yes.

This is a scenario that is likely repeated every year across the country in a variety of industries. In this case, a real estate developer engaged a video developer to produce a sales video for a residential condominium project. To capture the “lifestyleâ€Â of the neighbourhood, the video developer shot footage of local shops, bicycling paths, jogging trails, and other local amenities. In the course of this project, the plaintiff – a jogger – was caught on video, and after editing, a 2-second clip of the plaintiff was included in the final 2-minute promotional video.

Like all video, this one was posted to YouTube, where it lived for 1 week, before being taken down in response to the plaintiff’s complaints.

In Vanderveen v Waterbridge Media Inc., 2017 CanLII 77435 (ON SCSM), the court considered the claim that this clip of the jogger constituted a violation of privacy rights and appropriation of personality rights.  In the analysis, the court considered the tort of “intrusion upon seclusionâ€, which was designed to provide a remedy for conduct that intrudes upon private affairs where the invasion of privacy is considered “highly offensiveâ€.

The court in this case decided that a 2-second video clip of someone jogging on a public pathway does constitute a “highly offensive†invasion of a person’s private affairs. The plaintiff was awarded $4,000 for the breach of privacy rights and $100 for the appropriation of personality.

Some points to consider:

- It is unclear why the court did not spend more time considering the issue of “reasonable expectation of privacyâ€. A number of court decisions have looked at this issue as it relates to video or photography on public beaches, public schools and other public places. This is not a new issue in privacy law, but it appears to have been given short shrift in this decision.

- The impact of this decision must be put into context: it is an Ontario small claims court decision, so it won’t be binding on other courts. However, it may be referred to in other cases of this type. The decision is unlikely to be appealed considering the amounts at issue, so we probably won’t see a review of the analysis at a higher level of court.

- Consider the implications of this approach to privacy and personality rights in light of the use of drone footage in making promotional videos – something that is becoming more common as costs lower and access to this technology increases.

- When entering into contracts for any promotional or marketing collateral – website content, images, video footage, film, advertisements, print materials – both sides should review the terms to confirm who bears the risk of addressing complaints such as this one, and who bears the responsibility for obtaining consents or releases from recognizable individuals who appear in the media content.

For advice regarding privacy rights, personality rights, drone law, and video development contracts, contact Field Law.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsCopyright Appeal Considers “User-Generated Content”

By Richard Stobbe

In 2015 an independent film-maker shot a film critical of the Vancouver aquarium, using some footage over which the Aquarium claimed copyright.  The Aquarium moved to block the online publication of the film.

Last year we wrote about that dispute and the preliminary injunction that prevented publication of parts of that documentary. In Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre v. Charbonneau, 2017 BCCA 395 (CanLII),  the preliminary order was appealed, and the documentary film-maker won. The decision is noteworthy for a number of reasons:

- In a preliminary injunction, at the “balance of convenience” analysis, freedom of expression should be weighed, particularly in a case such as this, where the documentary film engages a topic of public and social importance. The court affirmed that freedom of expression is among the most fundamental rights possessed by Canadians.

- The Copyright Act has an exception related to “user-generated content” under section 29.21 of the Act. This unique provision has been somewhat neglected by the courts since it was introduced in 2012.  This case remains the sole judicial consideration of section 29.21. At the lower level, the judge did not sufficiently analyze the issue of “fair dealing”, including whether this content qualified as non-commercial user-generated content under s. 29.21. However, we will still have to wait until a trial on the merits, to see how the court will deal with the bounds of non-commercial user-generated content under the Copyright Act.

The court sided with the documentary film-maker and set aside the earlier injunction. If this case goes to trial, it will finally provide some guidance on the application of section 29.21.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsThe Google Injunction: US Federal Court Responds to Supreme Court of Canada

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in our recent summary of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decision in the ongoing fight between Google and Equustek Solutions, Google lost in Canada’s top court. Google promptly filed an application in US Federal Court in California its home jurisdiction, on July 24, 2017, Â seeking relief from the reach of the SCC order.

In a decision released November 2, 2017, the US court handed down its decision in Google v. Equustek, Case 5:17-cv-04207-EJD, N.D. Cal. (Nov. 2, 2017). The first few pages of the US decision provide a useful summary of the Google/Equustek story. The US Court entertained Google’s application that the SCC’s order is “unenforceable in the United States because it directly conflicts with the First Amendment, disregards the Communications Decency Act’s immunity for interactive service providers, and violates principles of international comity.”

The US court quickly concluded that Google is eligible in the US for Section 230 immunity under the Communications Decency Act. Essentially, under US law, Google is merely an intermediary or “interactive service provider”, and not a “publisher” of the offending content. As an intermediary, it takes the cover of certain provisions granting immunity from liability. Section 230 immunity is well-tilled soil in US courts, and Google has fought and won a number of cases under Section 230 already, so Google’s immunity was not news to Google.  By compelling the search engine to de-index content that is protected speech in America, the SCC order had the effect of undercutting Section 230 immunity for service providers, thereby undermining the goals of Section 230 which is to preserve free speech online.

This preliminary injunction releases Google – in the United States – from compliance with the Canadian court order. Whether Google is content to rely on this, or whether it will pursue a final decision on the full merits, and whether Google will apply to the Canadian court (as the SCC invited it to do) for a variance of the Canadian order… all remains to be seen.

Calgary – 15:00 MST

No comments

Worldwide Injunction… by Australian Court

By Richard Stobbe

Those familiar with the controversy surrounding the Google / Equustek saga will be interested to know that Canada is not alone in extending its reach in internet-related disputes. This worldwide injunction was issued by an Australian court against Twitter in the case of X. v. Twitter [2017] NSWSC 1300.

The case deals with an injunction application to stop the unauthorised publication of the plaintiff’s confidential information. The publication occurred in the form of ‘tweets’ of certain secret financial information of an (apparently) anonymous plaintiff. The plaintiff company, identified simply as ‘X’, brought an injunction application against Twitter, a non-party to the underlying dispute, arising from conduct of an (apparently) anonymous defendant.

The mystery defendant created a Twitter account impersonating the plaintiff’s CEO, and then leaked certain information via the Twitter platform. When a complaint was sent to Twitter, it removed the offending tweets and the reported account for a violation of Twitter’s online terms (https://twitter.com/rules), specifically the rules regarding impersonation. As so often happens with internet-based shenanigans, the offending conduct merely resurfaced under a different account, and it continued and escalated. The court was convinced that this conduct was “clearly suggestive of a malicious intention to harm the plaintiff.”

In this case, the Australian court had no trouble establishing jurisdiction over Twitter, although the company did not file any defence, nor did it submit to the Australian court in any way. Much like the Canadian court in Equustek, the Australian court indicated that its jurisdiction over non-parties, and its extra-territorial reach, was nothing new. It has been making orders of this kind long before Twitter.

The court agreed to uphold the orders against Twitter to reveal the anonymous subscriber’s identity and to cause the “Offending Material” to be removed everywhere in the world from the Twitter platform and Twitter’s websites.

So far, there are no reports that the decision has been appealed.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments