Copyright in Architectural Works: an update

By Richard Stobbe

Who owns the copyright in a building?  A few years ago, we looked at the issue of Copyright in House Plans, but let’s look at something bigger. Much bigger.

In Lainco inc. c. Commission scolaire des Bois-Francs, 2017 CF 825, the federal court reviewed a claim by an architectural engineering firm over infringement of copyright in the design for an indoor soccer stadium.

Lainco, the original engineers, sued a school board, an engineering firm, a general contractor and an architect, claiming that this group copied the unique design of Lainco’s indoor soccer complex. The nearly identical copycat structure built in neighbouring Victoriaville was considered by the court to be an infringement of the original Lainco design even though the copying covered functional elements of the structure. The court decided that such functional structures can be protected as “architectural works†under the Copyright Act, provided they comprise original expression, based on the talent and judgment of the author, and incorporate an architectural or aesthetic element.

The group of defendants were jointly and severally liable for the infringement damage award, which was assessed at over $700,000.

Make sure you clarify ownership of copyright in architectural designs with counsel to avoid these pitfalls.

Calgary – 07:00

No comments

IP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in Part 1, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patentâ€

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 2, let’s review the next couple of areas:

- Industrial Design or “Design Patentâ€:

I always tell my clients not to underestimate this lesser-known area of IP protection. It can be a very powerful tool in the IP toolbox. In both Canada (which uses the term industrial design) and the US (which refers to a design patent), this category of intellectual property only provides protection for ornamental aspects of the design of a product as long as they are not purely functional . To put this another way, features that are dictated solely by a utilitarian function of the article are ineligible for protection.

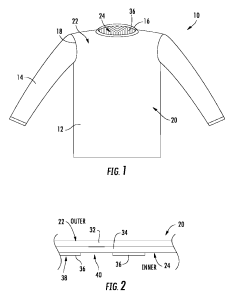

Registration is required and protection expires after 10 years. A registrable industrial design has to meet certain criteria: (i) it must differ substantially from the prior art (in other words it must be “originalâ€); (ii) it cannot closely resemble any other registered industrial designs; and (iii) it cannot have been published more than a year before application for registration. Some examples:  This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

This depicts a recent registration by Lululemon. The design comprises the pattern feature of a shirt as depicted in solid lines in the drawings. (The portions shown in stippled lines do not form part of the design.)

The solid lines on the image above represents a protected design registration filed by Nike.

TIP: Placement of a pocket on a t-shirt may not be considered innovative, but even minor differentiators can help distinguish a product in a crowded field. A design registration can support a blended strategy which also deploys other IP protection, such as trademark rights.

- Trademarks:

Every consumer will be intuitively familiar with the power of a brand name such as LULULEMON or NIKE, or the well-known Nike Swoosh Design. That topic is well-covered elsewhere. However, some brands take advantage of a lesser-known area of trademark rights: distinguishing guise protects the shape of the product or its packaging. It differs from industrial design, and one way to consider the distinction is that an industrial design protects new ornamental features of a product from when it is first used, whereas a distinguishing guise can be registered once it has been used in Canada so long that becomes a brand, distinctive of a manufacturer due to extensive use of the mark in the marketplace. It’s worth noting that the in-coming amendments to the Trademarks Act will do away with distinguishing guises.

One good example is the well-known shape of CROCS-brand sandals. The shape and appearance of the footwear itself has been used so long that it now functions as a brand to distinguish CROCS from other sandals. Just as with industrial design, the protected features cannot be dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.

Others have filed distinguishing guise registrations in Canada, including Canada Goose Inc. for coats and Hermès International for handbags.

TIP: For a distinguishing guise application, each applicant will have to file evidence to show that the mark is distinctive in the marketplace in Canada. That is not the case with a regular trademark, such a word mark or regular logo design.

We review the final areas of IP protection in Part 3.

Calgary – 7:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Evolution: Part 2 (When Technology Changes)

By Richard Stobbe

Technology certainly evolves. Can a trademark evolve? In the world of intellectual property rights, a registered trademark can live on for a hundred years or more. If you registered a trademark in the 1800s, it could still be valid today. But will the underlying product be delivered to customers the same way? (See: Goodbye Floppy Disk, Hello Streaming Video: Trademark Evolution, Part 2).

- In the 1980s Canadian courts recognized that service delivery can evolve in the decision in BMB Compuscience Canada Ltd v Bramalea Ltd. (1988), 22 CPR (3d) 561 (FCTD). In that case, BMB applied to register the mark NETMAIL in association with a computer program. But the NETMAIL product was not sold as a physical object, and courts have recognized that software vendors can experience “unique difficulties†when attempting to associate a trade-mark with its software, since there is no label, packaging or hang-tag, as with other types of goods. The court in BMB Compuscience was prepared to take a flexible approach and permit a software vendor like BMB to demonstrate “use†of its mark for the purposes of the Trade-marks Act where the brand was shown on a computer screen during product demonstrations.

- This concept was more recently applied in Davis LLP vs. 819805 Alberta Ltd., 2016 TMOB 64, a Section 45 challenge to the registered trademark BIBLIOTECA. The mark BIBLIOTECA was registered in association with certain software “goodsâ€. The goods were described as “Computer software, namely a computer database containing information for use in the field of building design and construction.â€Â During the relevant period, the database was accessed by customers as part of an online service, without the sale of any tangible or physical product. The BIBLIOTECA decision adopted the reasoning in BMB Compuscience to allow the trademark owner to demonstrate “use†of the mark in ways that reflected technological changes in the way this product was delivered to customers.

- In the United States, the USPTO is running a pilot program to allow amendments to identifications of goods and services in trademark registrations due to changes in technology, including many cases where floppy disks and cartridges are being updated to reflect online streaming. For example, the mark PHOTODISC, owned by Getty Images, was originally registered in association with stock photography “contained in digital format on CD-ROMs.â€Â Through the amendment process, Getty Images is proposing an amendment to reflect the changes in how its stock photo products are delivered: “in digital format on electronic or computer media or downloadable from databases or other facilities provided over global computer networks, wide area networks, local area networks, or wireless networks…â€

- Perhaps the best reflection of this is the US registered mark for THE MARCH OF TIME, used in association with newsreels and originally registered in 1935. Embedded in the original trademark application is a description of the technological breakthrough of allowing motion pictures to be broadcast with sound: “motion picture films for use in connection with synchronized apparatus for simultaneously reproducing coordinated light and sound effect.â€Sadly, this piece of history is now being replaced with the bland description “Providing non-downloadable online videos featuring historical newsreel.†I guess that evokes the march of time !

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Protection in the Fashion and Apparel Industry (Part 1)

.

By Richard Stobbe

Complex technology like blockchain is in fashion. What about IP protection for seemingly simple items like shirts, shoes and undergarments? As competitors jostle for position in the fashion and apparel marketplace, how do intellectual property rights apply? Make no mistake, IP rights in the fashion and apparel industry are fiercely contested. Fashion products can be protected in Canada using a number of different IP tools, including:

- confidential information

- patents

- industrial design or “design patent”

- trademarks

- trade dress

- copyright

- personality rights.

For many products, there will be an overlap in protection, and we’ll discuss some examples. In Part 1, let’s review the first two areas:

- Confidential Information

Confidential information or ‘trade secrets’ refers simply to information that has value to a designer or manufacturer because competitors don’t have access to the information. As long as the information is kept secret, and is only disclosed to others in confidence, then the secrets may remain protected as ‘trade secrets’ for many years. The confidential information may be made up of related business information, such as contacts of suppliers, pricing margins, new product ideas or prototype designs. The period of confidentiality may be short-lived in the case of a new product design: once the product is released to customers, it’s no longer confidential.

An owner of confidential information must take steps to maintain confidentiality, and the information should only be disclosed under strict terms of confidentiality (as part of a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), or confidentiality agreement).

If the confidential information is misappropriated, the owner can seek to enforce its rights by proving that the information has the required quality of confidentiality, the information was disclosed in confidence, and there was an unauthorized use or disclosure in a way that caused harm to the owner.

TIP: Ensure that you take practical steps to limit access to the confidential info. And when signing an NDA, make sure it doesn’t contain any terms that might inadvertently compromise confidentiality or give away IP rights.

- Patents

Many apparel and footwear companies rely heavily on patent protection to block competitors and gain an advantage in the marketplace.

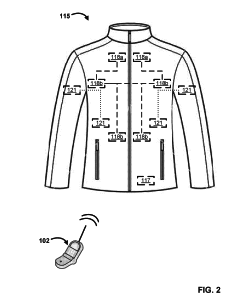

Let’s take a few examples. In pursuing the ‘holy grail’ of outdoor activewear, many manufacturers are seeking a comfortable, breathable jacket that can keep a wearer warm without overheating. The North Face System recently filed an application for a smart-sensing jacket using sensors to determine a “comfort signature” based on differences in environmental conditions between the sensors and making adjustments for the wearer.

A competitor – Under Armour Inc. – is seeking patent protection for garments incorporating printed ceramic materials to retain heat, without sacrificing other performance qualities such as  water and dirt repellency, durability, breathability and moisture-wicking qualities. In this patent application, Under Armour is seeking protection not only for the fabric but also the innovative method of manufacturing the fabric.

From high-tech jackets to innovative shoe designs, to more specific components, such as garment linings, or improved fasteners, patents can provide a valuable tool to ensure that a company’s research-and-development initiatives can bear fruit in the marketplace. By providing a period of exclusivity for the patent holder, this category of IP protection keeps the field clear of infringing replicas while the company recoups its investments and turns a profit on a successful product technology.

In the case of many fashion or apparel products, the time and cost of patent protection – it may take several years before a valid patent is issued – may not be justified in light of the high turn-over in seasonal product lines, and the ever-shifting tastes of consumers.

TIP: Make sure you consider both sides of the patent issue: as an inventor, an investment in patent protection may be worth considering, particularly in a product area where the underlying ‘technology’ or innovation may be commercialized over a number of years, such as the famous Gore-Tex fabric, even though superficial fashions may change during that time. On the flip side, manufacturers should take care to ensure that their own designs are not infringing the patent rights of some other patent holder.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 commentsThe Blockchain Patent Gold Rush

By Richard Stobbe

The blockchain technology underlying BitCoin and other cryptocurrencies was originally designed and conceived as an open protocol that would not be owned by any one centralized entity, whether government or private. Just like other foundational protocols that were created in the early days of the internet (email is based on POP, SMTP and IMAP, and websites rely on HTTP, and file transfers use FTP and TCP/IP), no-one really owns these protocols.  No-one collects royalties or patent licensing fees for the use of these protocols (…though some patent assertion entities might argue otherwise).

Similarly, the peer-to-peer vision underlying “the blockchain” was conceptually directed to maintaining the integrity of peer-to-peer transactions that function outside the realm of a centralized overseer such as a bank or government registry. Where, traditionally, a bank served as the trusted and verifiable record of a transaction, the use of blockchain technology could provide an alternative trusted and verifiable record of a transaction. No bank required.

It should come as no surprise, then, that banks are rushing to own a piece of this space.

A recent U.S. report shows: “The financial industry dominates the list of the top ten blockchain-related patent holders. … Leading the list is Bank of America with 43 patents, MasterCard International with 27 patents, FMR LLC (Fidelity) with 14 patents, and TD Bank with 11 patents. Other major financial institutions with blockchain patents include Visa Inc. with 7 patents, American Express with 6 patents, and Nasdaq Inc. with 5 patents.” (Blockchain Patent Filings Dominated by Financial Services Industry, Posted on January 12, 2018Â

Will the privatization of blockchain technologies spur adoption of this technology in the business-to-business layer? Or will the patent gold rush merely erect proprietary fences in a way that constrains adoption?

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments

Craft Beer Branding

By Richard Stobbe

In one of the more absurd episodes of bureaucratic overreach, craft brewer Stalwart Brewing Company ran into a regulatory headache when the LCBO raised concerns about the regulatory prohibition on health claims related to Stalwart’s label for ” Dr. Feelgood India Pale Ale”.

The regulator’s complaint was that the label – featuring a tongue-in-cheek portrayal of a snake wrapped around a mash-paddle-medieval-sword, mimicking a Rod of Asclepius – was somehow crossing the line by making unsubstantiated medical claims…Because apparently Canadian beer consumers wouldn’t be able to decipher that “Dr. Feelgood” is not a real physician, and might think that the IPA contained in the can was real medicine.

Leaving aside the thorny question of whether IPA qualifies as medicine, the branding and trademark issues arises in a number of ways:

- Trademark  searches can clear a proposed brand as against other similar marks which may be registered or pending for similar products;

- Trademark searches can be done in conjunction with the process of meeting federal and provincial labelling requirements;

- This case is a reminder that trademark preclearance must also take into account other rules, such as:

- alcohol by volume declarations;

- the correct naming for “low alcohol beer” vs. “light beer” vs. “extra strong beer”;

- “Lager” on its own is not an acceptable common name for beer. The common name “beer” must be listed in addition to the description “lager”;

- naming conventions related to gluten-free beer.

On a positive note, the original Dr. Feelgood cans should now be a collector’s item.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsA Software Vendor and its Customer: “like ships passing on a foggy nightâ€

By Richard Stobbe

When a customer got into a dispute with the software vendor about the license fees, the resulting case reads like a cautionary tale about software licensing. In ProPurchaser.com Inc. v. Wifidelity Inc., 2017 ONSC 7307 (CanLII), the court reviewed a dispute about a Software License Agreement. The customer, ProPurchaser, signed a license agreement with Wifidelity for the license of certain custom software at a rate of $6,000 per month. Over time, this fee increased and at the time the dispute commenced in 2017, ProPurchaser was paying a monthly fee of about $42,000.  The customer paid this fee, but apparently had no way of telling what it was paying for.

Detailed invoices were never submitted and so it was impossible to tell objectively how this fee should be broken down between license fees, support fees, expenses, or commissions.  The customer had formed the impression that this increase was due to support fees at an hourly rate, since the original license of $6,000 per month remained in effect and had never been amended in writing.

The software vendor, on the other hand, gave evidence that the license fee had increased under a verbal agreement between the parties.  “Based on the conflicting evidence,†the court mused, “it seems that the parties, much like ships passing on a foggy night, proceeded for several years unaware of the other’s different understanding about what was being charged by Wifidelity and paid for by ProPurchaser.â€

Under the Software License, either party was entitled to terminate without cause, by providing 14 days’ written notice to the other party. Eventually, the software vendor, Wifidelity, exercised the right of termination, triggering the lawsuit. ProPurchaser immediately sought a court order preserving the status quo, to prevent the software vendor from shutting down the software. In August, the court granted that order for a period of six months, subject to continuing payment of the $42,000 monthly license fee by ProPurchaser.  In November, ProPurchaser again approached the court, this time for an order extending the order until trial. Such an order could, in effect, be tantamount to a final resolution of the dispute, forcing the license to remain in effect. However, this would fly in the face of the clear terms of the agreement, which permitted for termination on 14 days’ notice.

While the dispute has yet to go to trial, there are some interesting lessons for software vendors and licensees:

- From a legal perspective, in order to succeed in its injunction application, ProPurchaser had to convince the court that termination of the license caused “irreparable harmâ€. However, the agreement itself allowed each party to terminate for no reason on very short notice, making it difficult to argue that this outcome – one that both sides had agreed to – would cause harm. If it caused so much harm, why did ProPurchaser agree to it in the first place? And in any event, any harm was compensable in damages and therefore not “irreparableâ€.

- That was a problem for the customer, when making a fairly narrow legal argument, but it’s also a problem from a business perspective. If the licensed software supports mission-critical functions within the licensee’s business, then make sure it’s not terminable for convenience by the software vendor.

- If changes are made to the software license agreement, particularly regarding the essential business terms like license fees and support fees, make sure these amendments are captured in writing, through a revised pricing schedule, or detailed invoicing that has been accepted by both sides.

Calgary – 13:00Â MST

No comments

Trademark Evolution: Part 1 (When Trademarks Change)

By Richard Stobbe

The famous Toblerone bar is so distinctive in shape and design that it serves as a great example of a “distinguishing guise†trademark. It has been used as a  trademark since 1910 in Canada, and during that time has maintained the same “tread design†of chocolate peaks, which has been a registered trademark in Canada since 1969.

It’s the actual shape of the bar that functions as a trademark. The bar is really a whole trademark treasure-trove since the unique shape of the triangular box, the colour scheme of the lettering, and the word TOBLERONE, are all separate trademarks, registered in a number of countries around the world.

The Swiss chocolatier redesigned the famous bar for the UK marketplace (reportedly in response to price adjustments required in the wake of Brexit). The newly redesigned bar expanded the valleys, resulting in fewer peaks, all to shave costs.  This of course resulted in a minor scandal in the UK, as well as some heartburn for the company’s trademark counsel.

If the mark-as-used departs from the mark-as-registered, there is a risk that the original registered mark has been abandoned, putting the strength of the registered rights at risk. This is a basic tenet of trademark law. While minor changes are permitted as a brand evolves, there is a point at which the changes go too far, essentially resulting in the adoption of a new mark.

Seeing this vulnerability, a competitor entered the marketplace with a bar “inspired by†the original Toblerone bar. Poundland, a UK discount retailer, introduced a double-peaked chocolate bar complete with knock-off packaging that mimics the distinctive gold background and red lettering of the original Toberlone package.

After a legal wrangle that reportedly kept the Poundland product off store shelves for several months, the dispute was settled and Poundland introduced modified packaging, featuring gold lettering against a blue background.

The lessons for business?

- In the field of consumer products, this is a good reminder that the shape of the product or its packaging can serve as a trademark, and can be registered as a means of  protecting brand rights.

- When a product or trademark evolves over time – whether in response to cost pressures, as in the Toblerone case, or in response to changes in the marketplace, or consumer demands – it’s important to measure the modified mark against the original mark, as it was registered. If the departure is too great, the rights to the original mark may be placed at risk.

Calgary – 09:00 MST

No commentsPrivacy Breach … While Jogging Down a Public Path?

.

By Richard Stobbe

An online video shows someone jogging on a public pathway during a 2-second clip. Let me get this straight… does this constitute a breach of privacy rights? According to an Ontario court, the answer is yes.

This is a scenario that is likely repeated every year across the country in a variety of industries. In this case, a real estate developer engaged a video developer to produce a sales video for a residential condominium project. To capture the “lifestyleâ€Â of the neighbourhood, the video developer shot footage of local shops, bicycling paths, jogging trails, and other local amenities. In the course of this project, the plaintiff – a jogger – was caught on video, and after editing, a 2-second clip of the plaintiff was included in the final 2-minute promotional video.

Like all video, this one was posted to YouTube, where it lived for 1 week, before being taken down in response to the plaintiff’s complaints.

In Vanderveen v Waterbridge Media Inc., 2017 CanLII 77435 (ON SCSM), the court considered the claim that this clip of the jogger constituted a violation of privacy rights and appropriation of personality rights.  In the analysis, the court considered the tort of “intrusion upon seclusionâ€, which was designed to provide a remedy for conduct that intrudes upon private affairs where the invasion of privacy is considered “highly offensiveâ€.

The court in this case decided that a 2-second video clip of someone jogging on a public pathway does constitute a “highly offensive†invasion of a person’s private affairs. The plaintiff was awarded $4,000 for the breach of privacy rights and $100 for the appropriation of personality.

Some points to consider:

- It is unclear why the court did not spend more time considering the issue of “reasonable expectation of privacyâ€. A number of court decisions have looked at this issue as it relates to video or photography on public beaches, public schools and other public places. This is not a new issue in privacy law, but it appears to have been given short shrift in this decision.

- The impact of this decision must be put into context: it is an Ontario small claims court decision, so it won’t be binding on other courts. However, it may be referred to in other cases of this type. The decision is unlikely to be appealed considering the amounts at issue, so we probably won’t see a review of the analysis at a higher level of court.

- Consider the implications of this approach to privacy and personality rights in light of the use of drone footage in making promotional videos – something that is becoming more common as costs lower and access to this technology increases.

- When entering into contracts for any promotional or marketing collateral – website content, images, video footage, film, advertisements, print materials – both sides should review the terms to confirm who bears the risk of addressing complaints such as this one, and who bears the responsibility for obtaining consents or releases from recognizable individuals who appear in the media content.

For advice regarding privacy rights, personality rights, drone law, and video development contracts, contact Field Law.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsThe Google Injunction: US Federal Court Responds to Supreme Court of Canada

By Richard Stobbe

As noted in our recent summary of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decision in the ongoing fight between Google and Equustek Solutions, Google lost in Canada’s top court. Google promptly filed an application in US Federal Court in California its home jurisdiction, on July 24, 2017, Â seeking relief from the reach of the SCC order.

In a decision released November 2, 2017, the US court handed down its decision in Google v. Equustek, Case 5:17-cv-04207-EJD, N.D. Cal. (Nov. 2, 2017). The first few pages of the US decision provide a useful summary of the Google/Equustek story. The US Court entertained Google’s application that the SCC’s order is “unenforceable in the United States because it directly conflicts with the First Amendment, disregards the Communications Decency Act’s immunity for interactive service providers, and violates principles of international comity.”

The US court quickly concluded that Google is eligible in the US for Section 230 immunity under the Communications Decency Act. Essentially, under US law, Google is merely an intermediary or “interactive service provider”, and not a “publisher” of the offending content. As an intermediary, it takes the cover of certain provisions granting immunity from liability. Section 230 immunity is well-tilled soil in US courts, and Google has fought and won a number of cases under Section 230 already, so Google’s immunity was not news to Google.  By compelling the search engine to de-index content that is protected speech in America, the SCC order had the effect of undercutting Section 230 immunity for service providers, thereby undermining the goals of Section 230 which is to preserve free speech online.

This preliminary injunction releases Google – in the United States – from compliance with the Canadian court order. Whether Google is content to rely on this, or whether it will pursue a final decision on the full merits, and whether Google will apply to the Canadian court (as the SCC invited it to do) for a variance of the Canadian order… all remains to be seen.

Calgary – 15:00 MST

No comments

Canada’s Top Court and the Google Injunction

By Richard Stobbe

When can a Canadian court reach across borders and control online activity that happens outside Canada? The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) handed down its decision in Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc., a case that started as a garden-variety intellectual property (IP) dispute, and ended up in the country’s top court as a significant guide for when the law will be imposed on those beyond Canadian borders, and those who are not even a party to the original dispute. The recent judgment deals with an IP owner – Equustek – who sought a practical remedy against an IP infringer, Datalink.

Equustek alleged that Datalink had engaged in misappropriation of trade secrets, passing off and breach of confidentiality. When Datalink refused to comply with the court’s original orders to cease sales of the allegedly infringing products, Equustek turned to Google, asking the search engine provider to block or de-list Datalink’s website. Equustek argued that it could only find an effective remedy against a determined infringer by blocking access to the infringing webpages, where the competing products were being sold by Datalink. (See our earlier posts for a more detailed summary of the facts of this case.)

The issue on appeal to the SCC was whether Google can be ordered, before a trial, to “globally de-index the websites of a company which, in breach of several court orders, is using those websites to unlawfully sell the intellectual property of another company.” Applying what it called “classic interlocutory injunction jurisprudence”, the SCC rejected Google’s counter-arguments and decided to uphold the injunction against Google. Thus the current state of the law in Canada is that non-party actors such as Google can be ordered by a Canadian court to take certain steps with worldwide effect, reaching outside Canada’s borders.

There are a number of fascinating elements to this case, which is why it has garnered so much attention and commentary. It’s worth emphasizing a few points from this controversial case:

1. Remember, Google was never a party to the original lawsuit. The search engine did nothing illegal or improper, nor was it implicated in the infringing conduct other than acting as a passive intermediary. However the Court noted that Google was so involved in facilitating the allegedly infringing behavior that the Court was justified in constraining Google’s activities in order to prevent the harmful conduct of the infringer. This, the Court said, is nothing new. Non-parties such as Google are often the subject of court orders.

2. Google had offered to block the search result listings from its < google.ca > site, but Equustek argued (and the Court agreed) that, to be effective, the order against Google had to be worldwide in effect. If restricted to Canada only, the order would not have the intended effect of preventing the irreparable harm to Equustek. “The Internet has no borders — its natural habitat is global,” said the Court. “The only way to ensure that the interlocutory injunction attained its objective was to have it apply where Google operates — globally. ”

However this ignores the fact that Equustek’s IP rights are not global in scope. Indeed, there was very little analysis of Equustek’s IP rights by any of the different levels of court, something noted by the dissent. Since this entire case involved pre-trial remedies, the merits of the underlying allegations and the strength of Equustek’s IP rights were never tested at trial. In order for the injunction to make sense, one must assumed that the IP rights were valid. Even so, Equustek’s rights couldn’t possibly be worldwide in nature. There was no evidence of any worldwide patent or trademark portfolio. So, the court somehow skipped from “the internet is borderless” to “the infringed rights are borderless” and are deserving of a worldwide remedy.

3. Lastly, Google raised a few other arguments – based on freedom of speech and international comity – that the Court batted away. Free speech, the Court argued, does not extend to protect the sale of articles that infringe IP rights. And as for international comity – the idea that each country should have mutual reciprocal respect for the laws of other countries in the international community, and that one law should not compel a person to break the laws of another country – the Court sidestepped this issue. Â If there is any such offense to the principles of international comity, said the Court, then Google is free to apply again to the Canadian courts to vary the order accordingly. At the date of the hearing at the SCC, Google had made no such application. However, as soon as the ink had dried on the judgement, Google applied to Federal Court in California, its home jurisdiction, seeking relief from the reach of the SCC order. This request has been supported by a line-up of intervenors in the US blaring headlines such as “Top Canadian Court Permits Worldwide Internet Censorship“!

A copy of Google’s motion for relief in the US court is here.

With this maneuver, Google may be writing a rule-book on how to delimit or constrain the scope of the SCC’s reach by appealing to US courts. As between Canada and the US, this may help clarify the limits of how Canadian court orders will impact US persons. Let’s not forget that US courts don’t hesitate to make extraterritorial orders of their own. Other countries routinely do the same, so this is by no means a uniquely Canadian scenario.

I noted in January, 2016 that this case was one to watch, and in 2017 it remains true. We will monitor and report back on the results of Google’s US Federal Court action.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentA sale in Canada triggers exhaustion of patent rights in the US

By Richard Stobbe

“Patent exhaustion” is something we’ve reviewed before. To recycle an old line, the term “patent exhaustion†does not refer to the feeling you get when a patent agent talks for 3 hours about the process of a patentee traversing a rejection in reexamination proceedings.

Nope, this is the patent law concept that the first authorized, unrestricted sale of a patented item ends, or “exhausts,†the patent-holder’s right to ongoing control of that item, leaving the buyer free to use or resell the patented item without restriction. For example, if you buy a patented widget from the patent owner, you can resell that widget to your neighbour without fear of infringing the patent.

What if the widget is sold by the U.S. patent holder in Canada? Does this exhaust the patent rights in the U.S.?

The US Supreme Court has recently confirmed that when the holder of a U.S. patent sells an item in an unrestricted sale, the patent holder does not retain patent rights in that product, even where that sale takes place outside the US. Thus, an authorized sale of the patented article in Canada by the U.S. patent holder would trigger exhaustion of the U.S. patent rights. The U.S. Supreme Court has confirmed that “An authorized sale outside the United States, just as one within the United States, exhausts all rights under the [U.S.] Patent Act.”

See: IMPRESSION PRODUCTS, INC. v. LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC. (Decided May 30, 2017)

Calgary -07:00 MST

No commentsWait… “GOOGLE” is not a generic word?

By Richard Stobbe

Is Google a brand or just a word meaning “conduct an online search”?

A trademark can suffer “genericide” when it becomes so commonly used that it transforms from a unique brand name into a generic word which is synonymous with a product or service. In a very interesting decision from the US Ninth Circuit Court Court of Appeals in Elliott and Gillespie v. Google Inc. , the trademark GOOGLE was challenged on this basis: that it had become a word describing “searching on the internet” in a general sense, rather than a being distinctive of search services provided through the GOOGLE-brand search engine.

The court had a good description of “genericide”: “Genericide occurs when the public appropriates a trademark and uses it as a generic name for particular types of goods or services irrespective of its source. For example, ASPIRIN, CELLOPHANE, and THERMOS were once protectable as arbitrary or fanciful marks because they were primarily understood as identifying the source of certain goods. But the public appropriated those marks and now primarily understands aspirin, cellophane, and thermos as generic names for those same goods.”

This case arose due to an underlying domain name complaint. Google asserted its trademark rights against Elliott and Gillespie based on their registration of hundreds of domain names that included the word “googleâ€; for example, “googledisney.com,†“googlebarackobama. net,†and “googlenewtvs.com.† Elliott and Gillespie fought back because hey, if you’re going to fight back, why not take on Google? They petitioned to cancel the trademark registrations for GOOGLE, which would in turn eliminate the basis for Google’s domain name complaint.

Elliott and Gillespie argued the “indisputable fact that a majority of the relevant public uses the word ‘google’ as a verb—i.e., by saying ‘I googled it,’ and … verb use constitutes generic use.”

The court reviewed the history of genericide under trademark law and applied a test of whether the relevant public understands a mark as describing where a product comes from, or what a product is.  Put another way, if a word still describes where the product comes from, then the term is still valid as a trademark.  But if consuming public understands the word to have become the product itself (and not the producer of the product), then the mark slips into being a generic term. Escalator is another example. It became synonymous with a moving staircase product, rather than distinctive of the Otis Elevator Company as the producer of that product.

In Google’s case, the court  asserted that verb use (the use of the mark as a verb instead of an adjective) does not automatically result in a finding of genericness. The court also noted that a claim of genericide must relate to a particular type of product or service. “In order to show that there is no efficient alternative for the word “google†as a generic term,” the court argued, “Elliott must show that there is no way to describe ‘internet search engines’ without calling them ‘googles.’ Because not a single competitor calls its search engine ‘a google,’ and because members of the consuming public recognize and refer to different ‘internet search engines,’ Elliott has not shown that there is no available substitute for the word ‘google’ as a generic term.”

Compare this to the case of Q-TIPS which concluded that “medical swab” and “cotton-tipped applicator” are efficient alternatives for the brand Q-TIPS, whereas a US case involving the ASPIRIN mark concluded that, at the time, there was no efficient substitute for the term “aspirin†because consumers did not know the term “acetylsalicylic acidâ€, so they used “aspirin” in a generic sense.  Interestingly, the brand ASPIRIN remains a registered mark in Canada, although Bayer lost its trademark rights to genericide in the US.

Google survived the genericide test this time. To keep track of future attempts to challenge Google’s trademark rights, please conduct an internet search using a GOOGLE® brand search engine.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsUS Drone Registry is Shot Down

By Richard Stobbe

In response to the proliferation of recreational drones in American skies, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) introduced a rule known as the “Registration Rule” in 2015. The rule required drone owners to register their drones with the FAA.  A recreational operator filed petitions in US Federal Court to challenge the FAA’s jursdiction to make the Registration Rule. The drone operator’s argument was that the FAA lacked statutory authority to issue the Registration Rule since it was outside the scope of the FAA’s jurisdiction. Last week, a  US Federal Court of Appeals decision  agreed and quashed the FAA’s Registration Rule.

This represents a set-back for the FAA’s regulatory reach over drones, and it illustrates the jurisdictional quandry of aviation regulators. In the US case, the FAA’s authority was actually curtailed by an earlier 2012 law, and this case did not turn upon a question of constitutional juridiction.

In Canada, there is a separation of powers between federal and provincial governments, and aviation falls into federal authority (as it does in the US). It is certainly open to drone operators to question the scope of the federal rule-making authority on constitutional grounds. In fact, in the drone industry that type of fight is likely to occur sooner or later in Canada.

If the FAA does not confirm its regulatory scope either through a court decision or amended legislation, then it won’t be able to maintain the drone Registration Rule. In any event, mere registration pales in comparison with the level of control that is suggested by this reported plan: The Trump administration is planning to ask Congress to give the federal government sweeping powers to “track, hack and destroy any type of drone over domestic soil with a new exception to laws governing surveillance, computer privacy and aircraft protection.”

This makes recent Canadian drone regulations positively benign by comparison.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsCopyright in Seismic Data is Confirmed

By Richard Stobbe

In a decision last year, GSI (Geophysical Service Incorporated) sued to win control over seismic data that it claimed to own. GSI used copyright principles to argue that by creating databases of seismic data, it was the proper owner of the copyright in such data. GSI argued that Encana, by copying and using that data without the consent of GSI, was engaged in copyright infringement. That was the core of GSI’s argument in multi-party litigation, which GSI brought against Encana and about two dozen other industry players, including commercial copying companies and data resellers. The data, originally gathered and “authored” by GSI, was required to be disclosed to regulators under the regime which governs Canadian offshore petroleum resources. Seismic data is licensed to users under strict conditions, and for a fee. Copying the seismic data, by any method or in any form, is not permitted under these license agreements. However, it is customary for many in the industry to acquire copies of the data from the regulator, after the privilege period expired, and many took advantage of this method of accessing such data.

A lower court decision in April 2016 (see: Geophysical Service Incorporated v Encana Corporation, 2016 ABQB 230 (CanLII)) Â agreed with GSI that seismic data could be protected by copyright. However, the court rejected the copyright infringement claims, saying that the regulatory regime permits the regulator to make such materials available for anyone – including industry stakeholders – to view and copy. Thus, GSI’s central infringement claim was dismissed.

GSI appealed, and in April, 2017 the Alberta Court of Appeal (Geophysical Service Incorporated v EnCana Corporation, 2017 ABCA 125 (CanLII)) unanimously agreed to uphold the lower court decision and reject GSI’s appeal. The decision confirmed that industry players have a legal right to use and copy such data after expiry of the confidentiality period, and the court was clear that regulators have the “unfettered and unconditional legal right … to disseminate, in their sole discretion as they see fit, all materials acquired … and collected under the Regulatory Regimeâ€. While the regulatory regime in this case does not specify that seismic data may be “copiedâ€, there are extensive provisions about “disclosureâ€, none of which list any restrictions after expiry or the confidentiality or privilege period. Thus, the ability to copy data is the only rational interpretation which aligns with the objectives of the legislation.

This decision will apply not only to the specific area of seismic data, but to any materials which are released to the public pursuant to a similar regulatory regime.

Field Law acted for two of the successful respondents in the appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Copyright Infringement on a Website: the risks of scraping and framing

By Richard Stobbe

If photos are available on the internet, then… they’re free for the taking, right?

Wait, that’s not how copyright law works? In the world of copyright, each original image theoretically has an “author” who created the image, and is the first owner of the copyright. The exception to this rule is that an image (or, indeed, any other copyright-protected work), which is created by an employee in the course of employment is owned by the employer. So, an image has an owner, even if that owner chose to post the image online. And copying that image without the permission of the owner could be an infringement of the owner’s copyright.

That seemingly simple question was the subject of a lawsuit between two rival companies who are in the business of listing online advertisements for new and used vehicles. Trader Corp. had a head start in the Canadian marketplace with its autotrader.ca website. Trader had the practice of training its employees and contractors to take vehicle photos in a certain way, with certain staging and lighting. A U.S. competitor, CarGurus, entered the market in 2015. It was CarGurus practice to obtain its vehicle images by “indexing†or “scraping†Dealers’ websites. Essentially, the CarGurus software would “crawl†an online image to identify data of interest, and then extract the data for use on the CarGurus site.

As part of its “indexing†or “scrapingâ€, the CarGurus site apparently included some photos that were owned by Trader. Although some back-and-forth between the parties resulted in the takedown of a large number of images from the CarGurus site, the dispute boiled over into litigation in late 2015 – the lawsuit by Trader alleged copyright infringement in relation to thousands of photos over which Trader claimed ownership.

Some interesting points arise from the decision in Trader v. CarGurus, 2017 ONSC 1841 (CanLII):

Trader was only able to establish ownership in 152,532 photos. There were thousands of photos for which Trader could not show convincing evidence of ownership. This speaks to the inherent difficulty in establishing a solid evidentiary record of ownership of individual images across a complex business operation.

CarGurus raised a number of noteworthy defences:

- First, CarGurus argued that in the case of some of the photos there was no actual “copying” or “reproduction” of the original image file. Rather, CarGurus argued that it merely framed the image files. Put another way, “although the images from Dealers’ websites appeared to be part of CarGurus’ website, they were not physically present on CarGurus’ server, but located on servers hosting the Dealers’ websites.”

The court was not convinced by the novel argument. “In my view” the court declared, “when CarGurus displayed the photo on its website, it was ‘making it available’ to the public by telecommunication (in a way that allowed a member of the public to have access to it from a place and at a time individually chosen by that member), regardless of whether the photo was actually stored on CarGurus’ server or on a third party’s server.”

The court decided that by making the images available to the public in through its framing technique, CarGurus infringed Trader’s copyright.

This tells us that copyright infringement can occur even where the infringer is not storing or hosting the copyright-protected work on its own server. - Second, CarGurus attempted to mount a “fair dealing” defense. It is not an infringement if the copying is for the purpose of “research or private study.” The court also rejected this argument, saying that even if a consumer was engaged in “research” when viewing the images in the course of car shopping, it would be too much of a stretch to accept that CarGurus was engaged in research. Theirs was clearly a commercial purpose.

- Lastly, the lawyers for CarGuru argued that, even if infringement did occur, CarGurus should be shielded from any damages award by virtue of section 41.27(1) of the Copyright Act. This provision was originally designed as a “safe harbour” for search engines and other network intermediaries who might inadvertently cache or reproduce copyright-protected works in the course of providing services, provided the search engine or intermediary met the definition of an “information location toolâ€. Although CarGurus does assist users with search functions (after all, it searches and finds vehicle listings), the court batted away this argument, pointing out that CarGurus cannot be considered an intermediary in the same way a search engine is. This particular subsection has never been the subject of judicial interpretation until now.

Having dismissed these defences, the Court assessed damages for copyright infringement at $2.00 per photo, for a total statutory damages award in the amount of $305,064.

CALGARY – 07:00 MT

No commentsDefamation with the Click of a Mouse: Assessing Damages

By Richard Stobbe

In the midst of a challenging period for a condominium owners association in a property located in Costa Rica, the president of the association resigned in frustration. Someone had overheard a rumour that the president resigned because he had been accused of theft. This rumour was false and when it was repeated by email – an email sent by means of the trusty ‘reply-all’ feature – all 37 condo owners were copied with the defamatory rumours.

An Ontario court recently rendered a decision in this email defamation case (McNairn v Murphy, 2017 ONSC 1678 (CanLII)), noting that the defamation occurred in ‘cyberspace’: “Communications via the Internet such as email, are potentially more pervasive than other forms of communication since control over its distribution is lost in numerous people may have access to it [and an] email containing a defamatory statement may be sent by [a] recipient to others who in turn may send it to an even larger audience. The Internet has the extraordinary capacity to replicate a defamatory statement, in [its] sleep. As a result, the mode in extent of publication, is [a] particularly significant consideration in assessing general damages [in]Internet defamation cases.”

In awarding damages of $160,000 against two defendants, the court noted that damages in defamation cases are assumed if publication of defamatory statements is evidenced, assuming there are no defences. The defamed individual need not show any specific loss. General damages in defamation cases can serve three functions:

(a) to console the plaintiff for the distress suffered in the publication of the defence;

(b) to repair the harm to the plaintiff’s reputation including, where relevant, business reputation; and

(c) to vindicate the plaintiff’s reputation.

The court applied the following six factors in determining general damages in defamation cases:

1. the plaintiff’s position and standing;

2. the nature and seriousness of the defamatory statements;

3. the mode or type of publication;

4. the absence or refusal to retract or apologize for the statements;

5. the conduct and motive of the defendant; and

6. the presence of aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

Defamation by means of mouse click is easy to do.

And, it should be noted, it’s not that difficult to make a full retraction and apology by the click of a mouse, particularly in a small community of 37 individuals. From the facts available in this case, an unreserved retraction and sincere apology may have been worth $160,000.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsPatent Infringement for Listing on eBay?

By Richard Stobbe

A patent owner notices that knock-off products are listed for sale on eBay. The knock-offs appear to infringe his patent. When eBay refuses to remove the allegedly infringing articles. The patent owner sues eBay for patent infringement, claiming that eBay is infringing the patent merely by hosting the listings, since listing the infringing articles amounts to an infringing “sale†or an infringing “offer to sell†the patented invention.

These are the facts faced by a U.S. court in Blazer v. eBay Inc. which decided that merely listing the articles for sale does not constitute patent infringement by means of an infringing sale, where it’s clear that the articles are not owned by eBay and are not directly sold by eBay. In fact, in the eBay model the seller makes a sale directly to the buyer – eBay can be characterized as a platform for hosting third party listings, rather than a seller. Â

Some interesting points arise from this decision:

- Prior patent infringement cases involving Amazon and Alibaba have suggested that the court will look closely at how the items are listed. For example, in those earlier cases, the court noted the use of the term “supplier” to describe the party selling the item, whereas the word “seller” is used in the eBay model. The term “supplier” might be taken to mean that the listing party is merely supplying the item to the platform provider, such as Amazon or Alibaba, who then sells to the end-buyer. Whereas the term “seller” identifies that the listing party is entering into a separate transaction with the end-buyer, leaving the platform provider out of that buy-sell transaction.

- The court in Blazer was clear that it will look at the entire context of the exchange to determine not only if an offer is being made, but who is making the offer.

- The “Terms of Use” or “Terms of Service” will be scrutinized by the court to help with this determination. The eBay terms explicitly advise users that eBay is not making an offer through a listing, and eBay lacks title and possession of the items listed.

Related Reading: eBay Not Liable for Listing Infringing Products of Third-Party Sellers – Not an Offer to Sell by eBay

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsCanadian Copyright & Breach of Technological Protection Measures (TPMs): $12.7 million in Damages

By Richard Stobbe

It’s always exciting when there’s a new decision about an obscure 5-year old subsection of the Copyright Act! Back in 2012, Canada changed its Copyright Act to try and drag it into the 21st century. Among the 2012 changes were provisions to prohibit the circumvention of TPMs. In plain English, this means that breaking digital locks would be a breach of the Copyright Act.

In Nintendo of America Inc. v. King and Go Cyber Shopping (2005) Ltd. the Federal Court reviewed subsections 41 and 41.1 of the Act. In this case, the defendant Go Cyber Shopping was sued for circumvention of the TPMs which protected Nintendo’s well-known handheld video game consoles known as the Nintendo DS and 3DS, and the Wii home video game console.  Specifically, Nintendo’s TPMs were designed to protect the code in Nintendo’s game cards (in the case of DS and 3DS games) and discs (in the case of Wii games).

The defendants were sued for copyright infringement (for the copying of the code and data files in the game cards and discs) and for circumvention of the TPMs. Interestingly (for copyright lawyers), the claim was based on “secondary infringement” which resulted from the authorization of infringing acts when Go Cyber Shopping provided its customers with instructions on how to copy Nintendo’s data.

The Court agreed that Nintendo’s digital locks qualified as “technological protection measures” for the purposes of the Act. The open-ended language of the TPM definition permits copyright owners to protect their business models with “any technological tool at their disposal.” This is an important acknowledgement for copyright owners, as it expands the range of technical possibilities, based on the principle of “technological neutrality†which avoids discrimination against any particular type of technology, device, or component. To put this another way, a copyright owner should be able to fit into the definition of a TPM  fairly easily since there is no specific technical criteria, aside from the general reference to an “effective technology, device or component that, in the ordinary course of its operation, controls access to a work…”

Next, the court agreed with Nintendo that Go Cyber Shopping has engaged in “circumvention” which means “to descramble a scrambled work or decrypt an encrypted work or to otherwise avoid, bypass, remove, deactivate or impair the technological protection measure…”

Lastly, Nintendo sought statutory damages, which avoids the need to show actual damages, and instead relies on automatic damages at a set amount. The court has a range from which to pick.  Nintendo suggested statutory damages between $294,000 to $11,700,000 for TPM circumvention of 585 different Nintendo Games, based on a statutorily mandated range between $500 and $20,000 per work. For copyright infringement, the evidence showed infringement of 3 so-called “Header Data” files. The court was convinced to award damages at the highest level of the range.

In the end the court made an award in favour of Nintendo, setting statutory damages at $11,700,000 for TPM circumvention in respect of its 585 Nintendo Games, and of $60,000 for copyright infringement in respect of the three Header Data works. This shows that TPM circumvention, as a remedy for copyright owners, has real teeth and may, in the right circumstances, easily surpass the damages awarded for copyright infringement. On top of this, the court awarded punitive damages of $1,000,000 in light of the “strong need to deter and denounce such activities.” Total… $12.7 million.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Interim Canadian drone rules launched

By Richard Stobbe

As the recreational and commercial use of drones expands, the calls for a regulatory framework have grown louder. The Canadian federal government has, until last week, taken the simple approach of prohibiting the use of UAVs: “No person shall operate an unmanned air vehicle in flight except in accordance with a special flight operations certificate or an air operator certificate.” Essentially, any commercial use of drones or use of drones that weigh more than 35 kg had to be registered with a Special Flight Operations Certificate (SFOC) through Transport Canada.

So far, the system of regulatory control was simplistic but not exactly scaleable, considering the explosive growth in this area.

Last week, as part of its effort to bring order to the chaos, the Canadian federal government released its Interim Order Respecting the Use of Model Aircraft under the Canadian Aviation Regulations which fall under the Aeronautics Act.

Now, if you fly your drone for recreational purposes and it weighs between 250 g and 35 kg, you don’t need an SFOC from Transport Canada to fly. But wait… there’s more!

This interim order essentially classifies small recreational drones as “model aircraft”, keeps the distinction for “unmanned air vehicles”, and adds some regulatory details.  The old regulations took a broad brush approach to the relatively small population of model aircraft hobbyists (hey guys… don’t fly into a cloud or in a manner that is hazardous to aviation safety). By contrast, the new rules provide a more objective set of criteria. Now, a person must not operate a recreational drone or model aircraft:

- at an altitude greater than 300 feet AGL;

- at a lateral distance of less than 250 feet (75m) from buildings, structures, vehicles, vessels, animals and the public;

- within 9 km of an aerodrome;

- unless it is operated within VLOS (visual line-of-sight) at all times during the flight;

- at a lateral distance of more than 1640 feet (500 m) from the person’s location;

- within controlled airspace;

- within restricted airspace;

- over or within a forest fire area, or any area that is located within 9 km of a forest fire area;

- over or within the security perimeter of a police or first responder emergency operation site;

- over or within an open-air assembly of persons;

- at night;

- in cloud;

- while operating another drone or model aircraft;

- unless the name, address and telephone number of the owner is clearly made visible on the aircraft.

Sigh… one can’t help a certain nostalgia for any regulation that still uses the word “aerodrome”. Those are just some of the new drone rules. Drones used for commercial or research purposes still require an SFOC.

For breach of the rules applying to recreational use, there are fines of between $3,000 and $15,000.

For our readers in Calgary, check out Taking Off: Drone Law in Canada where our Emerging Technologies Group presents an overview of the legal landscape surrounding drone use and discusses what you need to know to use drones in your business. The seminar will cover topics including:

- Discussion of the current regulatory approach at the federal, provincial and municipal level

- Potential privacy, contract and insurance issues

- Drone-related liability

- Patent/intellectual property protection

Additional Reading:Â The Wild West: Drone Laws And Privacy In Canada

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments