Copyright in Seismic Data is Confirmed

By Richard Stobbe

In a decision last year, GSI (Geophysical Service Incorporated) sued to win control over seismic data that it claimed to own. GSI used copyright principles to argue that by creating databases of seismic data, it was the proper owner of the copyright in such data. GSI argued that Encana, by copying and using that data without the consent of GSI, was engaged in copyright infringement. That was the core of GSI’s argument in multi-party litigation, which GSI brought against Encana and about two dozen other industry players, including commercial copying companies and data resellers. The data, originally gathered and “authored” by GSI, was required to be disclosed to regulators under the regime which governs Canadian offshore petroleum resources. Seismic data is licensed to users under strict conditions, and for a fee. Copying the seismic data, by any method or in any form, is not permitted under these license agreements. However, it is customary for many in the industry to acquire copies of the data from the regulator, after the privilege period expired, and many took advantage of this method of accessing such data.

A lower court decision in April 2016 (see: Geophysical Service Incorporated v Encana Corporation, 2016 ABQB 230 (CanLII)) Â agreed with GSI that seismic data could be protected by copyright. However, the court rejected the copyright infringement claims, saying that the regulatory regime permits the regulator to make such materials available for anyone – including industry stakeholders – to view and copy. Thus, GSI’s central infringement claim was dismissed.

GSI appealed, and in April, 2017 the Alberta Court of Appeal (Geophysical Service Incorporated v EnCana Corporation, 2017 ABCA 125 (CanLII)) unanimously agreed to uphold the lower court decision and reject GSI’s appeal. The decision confirmed that industry players have a legal right to use and copy such data after expiry of the confidentiality period, and the court was clear that regulators have the “unfettered and unconditional legal right … to disseminate, in their sole discretion as they see fit, all materials acquired … and collected under the Regulatory Regimeâ€. While the regulatory regime in this case does not specify that seismic data may be “copiedâ€, there are extensive provisions about “disclosureâ€, none of which list any restrictions after expiry or the confidentiality or privilege period. Thus, the ability to copy data is the only rational interpretation which aligns with the objectives of the legislation.

This decision will apply not only to the specific area of seismic data, but to any materials which are released to the public pursuant to a similar regulatory regime.

Field Law acted for two of the successful respondents in the appeal.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Copyright Infringement on a Website: the risks of scraping and framing

By Richard Stobbe

If photos are available on the internet, then… they’re free for the taking, right?

Wait, that’s not how copyright law works? In the world of copyright, each original image theoretically has an “author” who created the image, and is the first owner of the copyright. The exception to this rule is that an image (or, indeed, any other copyright-protected work), which is created by an employee in the course of employment is owned by the employer. So, an image has an owner, even if that owner chose to post the image online. And copying that image without the permission of the owner could be an infringement of the owner’s copyright.

That seemingly simple question was the subject of a lawsuit between two rival companies who are in the business of listing online advertisements for new and used vehicles. Trader Corp. had a head start in the Canadian marketplace with its autotrader.ca website. Trader had the practice of training its employees and contractors to take vehicle photos in a certain way, with certain staging and lighting. A U.S. competitor, CarGurus, entered the market in 2015. It was CarGurus practice to obtain its vehicle images by “indexing†or “scraping†Dealers’ websites. Essentially, the CarGurus software would “crawl†an online image to identify data of interest, and then extract the data for use on the CarGurus site.

As part of its “indexing†or “scrapingâ€, the CarGurus site apparently included some photos that were owned by Trader. Although some back-and-forth between the parties resulted in the takedown of a large number of images from the CarGurus site, the dispute boiled over into litigation in late 2015 – the lawsuit by Trader alleged copyright infringement in relation to thousands of photos over which Trader claimed ownership.

Some interesting points arise from the decision in Trader v. CarGurus, 2017 ONSC 1841 (CanLII):

Trader was only able to establish ownership in 152,532 photos. There were thousands of photos for which Trader could not show convincing evidence of ownership. This speaks to the inherent difficulty in establishing a solid evidentiary record of ownership of individual images across a complex business operation.

CarGurus raised a number of noteworthy defences:

- First, CarGurus argued that in the case of some of the photos there was no actual “copying” or “reproduction” of the original image file. Rather, CarGurus argued that it merely framed the image files. Put another way, “although the images from Dealers’ websites appeared to be part of CarGurus’ website, they were not physically present on CarGurus’ server, but located on servers hosting the Dealers’ websites.”

The court was not convinced by the novel argument. “In my view” the court declared, “when CarGurus displayed the photo on its website, it was ‘making it available’ to the public by telecommunication (in a way that allowed a member of the public to have access to it from a place and at a time individually chosen by that member), regardless of whether the photo was actually stored on CarGurus’ server or on a third party’s server.”

The court decided that by making the images available to the public in through its framing technique, CarGurus infringed Trader’s copyright.

This tells us that copyright infringement can occur even where the infringer is not storing or hosting the copyright-protected work on its own server. - Second, CarGurus attempted to mount a “fair dealing” defense. It is not an infringement if the copying is for the purpose of “research or private study.” The court also rejected this argument, saying that even if a consumer was engaged in “research” when viewing the images in the course of car shopping, it would be too much of a stretch to accept that CarGurus was engaged in research. Theirs was clearly a commercial purpose.

- Lastly, the lawyers for CarGuru argued that, even if infringement did occur, CarGurus should be shielded from any damages award by virtue of section 41.27(1) of the Copyright Act. This provision was originally designed as a “safe harbour” for search engines and other network intermediaries who might inadvertently cache or reproduce copyright-protected works in the course of providing services, provided the search engine or intermediary met the definition of an “information location toolâ€. Although CarGurus does assist users with search functions (after all, it searches and finds vehicle listings), the court batted away this argument, pointing out that CarGurus cannot be considered an intermediary in the same way a search engine is. This particular subsection has never been the subject of judicial interpretation until now.

Having dismissed these defences, the Court assessed damages for copyright infringement at $2.00 per photo, for a total statutory damages award in the amount of $305,064.

CALGARY – 07:00 MT

No commentsCanadian Copyright & Breach of Technological Protection Measures (TPMs): $12.7 million in Damages

By Richard Stobbe

It’s always exciting when there’s a new decision about an obscure 5-year old subsection of the Copyright Act! Back in 2012, Canada changed its Copyright Act to try and drag it into the 21st century. Among the 2012 changes were provisions to prohibit the circumvention of TPMs. In plain English, this means that breaking digital locks would be a breach of the Copyright Act.

In Nintendo of America Inc. v. King and Go Cyber Shopping (2005) Ltd. the Federal Court reviewed subsections 41 and 41.1 of the Act. In this case, the defendant Go Cyber Shopping was sued for circumvention of the TPMs which protected Nintendo’s well-known handheld video game consoles known as the Nintendo DS and 3DS, and the Wii home video game console.  Specifically, Nintendo’s TPMs were designed to protect the code in Nintendo’s game cards (in the case of DS and 3DS games) and discs (in the case of Wii games).

The defendants were sued for copyright infringement (for the copying of the code and data files in the game cards and discs) and for circumvention of the TPMs. Interestingly (for copyright lawyers), the claim was based on “secondary infringement” which resulted from the authorization of infringing acts when Go Cyber Shopping provided its customers with instructions on how to copy Nintendo’s data.

The Court agreed that Nintendo’s digital locks qualified as “technological protection measures” for the purposes of the Act. The open-ended language of the TPM definition permits copyright owners to protect their business models with “any technological tool at their disposal.” This is an important acknowledgement for copyright owners, as it expands the range of technical possibilities, based on the principle of “technological neutrality†which avoids discrimination against any particular type of technology, device, or component. To put this another way, a copyright owner should be able to fit into the definition of a TPM  fairly easily since there is no specific technical criteria, aside from the general reference to an “effective technology, device or component that, in the ordinary course of its operation, controls access to a work…”

Next, the court agreed with Nintendo that Go Cyber Shopping has engaged in “circumvention” which means “to descramble a scrambled work or decrypt an encrypted work or to otherwise avoid, bypass, remove, deactivate or impair the technological protection measure…”

Lastly, Nintendo sought statutory damages, which avoids the need to show actual damages, and instead relies on automatic damages at a set amount. The court has a range from which to pick.  Nintendo suggested statutory damages between $294,000 to $11,700,000 for TPM circumvention of 585 different Nintendo Games, based on a statutorily mandated range between $500 and $20,000 per work. For copyright infringement, the evidence showed infringement of 3 so-called “Header Data” files. The court was convinced to award damages at the highest level of the range.

In the end the court made an award in favour of Nintendo, setting statutory damages at $11,700,000 for TPM circumvention in respect of its 585 Nintendo Games, and of $60,000 for copyright infringement in respect of the three Header Data works. This shows that TPM circumvention, as a remedy for copyright owners, has real teeth and may, in the right circumstances, easily surpass the damages awarded for copyright infringement. On top of this, the court awarded punitive damages of $1,000,000 in light of the “strong need to deter and denounce such activities.” Total… $12.7 million.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments

Is there copyright in a screenshot?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Ever wanted to remove something after it had been swallowed up in the gaping maw of the internet? Then you will relate to this story about an individual’s struggle to have certain content deleted from the self-appointed memory banks of the web.

The Federal Court recently rendered a procedural decision in the case of Davydiuk v. Internet Archive Canada and Internet Archive 2016 FC 1313 (for background, visit the Wayback Machine… or see our original post Copyright Implications of a “Right to be Forgottenâ€? Or How to Take-Down the Internet Archive).

For those who forget the details, this case relates to a long-running plan by Mr. Davydiuk to remove certain adult video content in which he appeared about a dozen years ago. He secured the copyright in the videos and all related material including images and photographs, and went about using copyright to remove the online reproductions of the content. In 2009, he discovered that Internet Archive, a defendant in these proceedings, was hosting some of this video material as part of its web archive collection.  It is Mr. Davydiuk’s apparent goal to remove all of the content from the Internet Archive – not only the video but also associated images, photos, and screenshots taken from the video.

The merits of the case are still to be decided, but the Federal Court has decided a procedural matter which touches upon an interesting copyright question:

When a screenshot is taken from a video, is there sufficient originality for copyright to extend to that screenshot? Or is it a “purely mechanical exercise not capable of copyright protection”?

This case is really about the use of copyright in aid of personal information and privacy goals. The Internet Archive argued that it shouldn’t be obliged to remove material for which there is no copyright. Remember, for copyright to attach to a work, it must be “original”. The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has made it clear that:

For a work to be “original†within the meaning of the Copyright Act, it must be more than a mere copy of another work. At the same time, it need not be creative, in the sense of being novel or unique. What is required to attract copyright protection in the expression of an idea is an exercise of skill and judgment. By skill, I mean the use of one’s knowledge, developed aptitude or practised ability in producing the work. By judgment, I mean the use of one’s capacity for discernment or ability to form an opinion or evaluation by comparing different possible options in producing the work. This exercise of skill and judgment will necessarily involve intellectual effort. The exercise of skill and judgment required to produce the work must not be so trivial that it could be characterized as a purely mechanical exercise. For example, any skill and judgment that might be involved in simply changing the font of a work to produce “another†work would be too trivial to merit copyright protection as an “original†work. [Emphasis added]

From this, we know that changing font (without more) is NOT sufficient to qualify for the purposes of originality. Making a “mere copy” of another work is also not considered original. For example, an exact replica photo of a photo is not original, and the replica photo will not enjoy copyright protection.  So where does a screenshot fall?

The Internet Archive argued that the video screenshots were not like original photographs, but more like a photo of a photo – a mere unoriginal copy of a work requiring a trivial effort.

On the other side, the plaintiff argued that someone had to make a decision in selecting which screenshots to extract from the original video, and this represented an exercise of sufficient “skill and judgment”. The SCC did not say that the bar for “skill and judgment” is very high – it just has to be higher than a purely mechanical exercise.

At this stage in the lawsuit, the court merely found that there was enough evidence to show that this is a genuine issue. In other words, the issue is a live one, and it has to be assessed with the benefit of all the evidence. So far, the issue of copyright in a screenshot is still undetermined, but we can see from the court’s reasoning that if there is evidence of the exercise of “skill and judgment” involved in the decision-making process as to which particular screenshots to take, then these screenshots will be capable of supporting copyright protection.

Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsIP Licenses & Bankruptcy (Part 2 – Seismic Data)

By Richard Stobbe

What happens to a license for seismic data when the licensee suffers a bankruptcy event?

In Part 1, we looked at a case of bankruptcy of the IP owner.

However, what about the case where the licensee is bankrupt? In the case of seismic, we’re talking about the bankruptcy of the company that is licensed to use the seismic data. Most seismic data agreements are licenses to use a certain dataset subject to certain restrictions. Remember, licences are simply contractual rights.  A trustee or receiver of a bankrupt licensee is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the trustee or receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts.

The only limitation is that a trustee cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, a seismic data license agreement does not grant a property right; it does not transfer a property interest in the data. It’s merely a contractual right to use. Bankruptcy trustees have the ability to disclaim these license agreements.

Can a trustee transfer the license to a new owner? If the seismic data license is not otherwise terminated on bankruptcy of the licensee, and depending on the assignment provisions within that license agreement, then it may be possible for the trustee to transfer the license to a new licensee. Transfer fees are often payable under the terms of the license. Assuming transfer is permitted, the transfer is not a transfer of ownership of the underlying dataset, but a transfer of the license agreement which grants a right to use that dataset.

The underlying seismic data is copyright-protected data that is owned by a particular owner. Even if a copy of that dataset is “sold” to a new owner in the course of a bankruptcy sale, it does not result in a transfer of ownership of the copyright in the seismic data, but rather merely a transfer of the license agreement to use that data subject to certain restrictions and conditions.

A purchaser who acquires a seismic data license as part of a bankruptcy sale is merely acquiring a limited right to use, not an unrestricted ownership interest in the data. The purchaser is stepping into the shoes of the bankrupt licensee and can only acquire the scope of rights enjoyed by the original licensee – neither more nor less. Any use of that data by the new licensee outside the scope of those rights would be a breach of the license agreement, and may constitute copyright infringement.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

No commentsHappy Birthday… in Trademarks

ipbog.ca turns 10 this month. It’s been a decade since our first post in October 2006 and to commemorate this milestone …since no-one else will… let’s have a look at IP rights and birthdays.

You may have heard that the lyrics and music to the song “Happy Birthday” were the subject of a protracted copyright battle. The lawsuit came as a surprise to many people, considering this is the “world’s most popular song” (apparently beating out Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven, but that’s another copyright story for another time).  Warner Music Group claimed that they owned the copyright to “Happy Birthday”, and when the song was used for commercial purposes (movies, TV shows, commercials), Warner Music extracted license fees, to the tune of $2 million each year. When this copyright claim was finally challenged, a US court ruled that Warner Music did not hold valid copyright, resulting in a $14 million settlement of the decades-old dispute in 2016.

In the realm of trademarks, a number of Canadian trademark owners lay claim to HAPPY BIRTHDAY including:

- The Section 9 Official Mark below, depicting a skunk or possibly a squirrel with a top hat, to celebrate Toronto’s sesquicentennial. Hey, don’t be too hard on Toronto, it was the ’80s.

- Another Section 9 Official Mark, the more staid “HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986” to celebrate that city’s centennial. Because nothing says ‘let’s party’ like the words HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986.

- Cartier’s marks HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA511885 and TMA779496) in association with handbags, eyeglasses and pens.

- Mattel’s mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA221857) in association with dolls and doll clothing.

- The mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY VINEYARDS (pending) for wine, not to be confused with BIRTHDAY CAKE VINEYARDS (also pending) also for wine.

- FTD’s marks BIRTHDAY PARTY (TMA229547) and HAPPY BIRTHTEA! (TMA484760) for “live cut floral arrangements”

- And for those who can’t wait until their full birthday there’s the registered mark HALFYBIRTHDAYÂ Â (TMA833899 and TMA819609) for greeting cards and software.

- The registered mark BIRTHDAY BLISS (TMA825157) for “study programs in the field of spiritual and religious development”.

- Let’s not forget BIRTHDAYTOWN (TMA876458) for novelty items such as “key chains, crests and badges, flags, pennants, photos, postcards, photo albums, drinking glasses and tumblers, mugs, posters, pens, pencils, stick pins, window decals and stickers”.

- Of course, no trademark list would be complete without including McDonald’s MCBIRTHDAY mark (TMA389326) for restaurant services.

So, pop open a bottle of branded wine and enjoy some live cut floral arrangements and a McBirthday® burger as you peruse a decade’s worth of Canadian IP law commentary.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

Brexit’s impact on IP Rights

By Richard Stobbe

The  UK’s Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA) has released a helpful 12-page summary entitled The Impact of Brexit on Intellectual Property, which discusses a number of IP topics and the anticipated impact on IP rights and transactions, including:

- EPC, PCT and UK patents

- Community trade marks

- Trade secrets

- Copyright

- IP disputes and IP transactions

It is CIPA’s position that IP rights holders should expect “business as usual” in the next few years, since existing UK national IP rights are unaffected, European patents and applications remain unaffected, and the UK Government has not even taken steps to trigger “Article 50” which would put in motion the formal bureaucratic machinery to leave the EU. This step is not expected until late 2016 or early 2017, which means the final exit may not occur until 2019.

Canadian rightsholders who have UK or EU-based IP rights are encouraged to consult IP counsel regarding their IP rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 comment

Bozo’s Flippity-Flop and Shooting Stars: A cautionary tale about rights management

By Richard Stobbe

If you’ve ever taken piano lessons then titles like “Bozo’s Flippity-Flop”, “Shooting Stars” and “Little Elves and Pixies” may be familiar.

These are among the titles that were drawn into a recent copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the Royal Conservatory against a rival music publisher for publication of a series of musical works. In Royal Conservatory of Music v. Macintosh (Novus Via Music Group Inc.) 2016 FC 929, the Royal Conservatory and its publishing arm Frederick Harris Music sought damages for publication of these works by Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music.

The case serves as a cautionary tale about records and rights management, since much of the confusion between the parties, and indeed within the case itself, could be blamed on missing or incomplete records about who ultimately had the rights to the musical works at issue. In particular, a 1999 agreement which would have clarified the scope of rights, was completely missing. The court ultimately determined that there was no evidence that the defendants Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music could benefit from any rights to publish these songs; the missing 1999 agreement was never assigned or extended to the defendants.

In assessing damages for infringement, the court reviewed the factors set forth in the Copyright Act, including:

- Â the good faith or bad faith of the defendant;

- Â the conduct of the parties before and during the proceedings;

- Â the need to deter other infringements of the copyright in question;

- Â in the case of infringements for non-commercial purposes, the need for an award to be proportionate to the infringements, in consideration of the hardship the award may cause to the defendant, whether the infringement was for private purposes or not, and the impact of the infringements on the plaintiff.

In evaluating the deterrence factor, the court noted: “it is unclear what effect a large damages award would have in deterring further copyright infringement, when the infringement at issue here appears to be the product of poor record-keeping and rights management on the part of both parties.  If anything, this case is instructive that the failure to keep crucial contracts muddies the waters around rights, and any resulting infringement claims. The Respondents should not alone bear the brunt of this laxity, because the Applicants played an equal part in the inability to provide to the Court the key document at issue.” [Italics added]

For these reasons, the court set per work damages at the lowest end of the commercial range ($500 per work), for a total award of $10,500 in damages.

Calgary – o7:00 MST

No commentsProtective Order for Source Code

By Richard Stobbe

A developer’s source code is considered the secret recipe of the software world – the digital equivalent of the famed Coca-Cola recipe. In Google Inc. v. Mutual, 2016 BCSC 1169 (CanLII),  a software developer sought a protective order over source code that was sought in the course of U.S. litigation. First, a bit of background.

This was really part of a broader U.S. patent infringement lawsuit (VideoShare LLC v. Google Inc. and YouTube LLC) between a couple of small-time players in the online video business: YouTube, Google, Vimeo, and VideoShare. In its U.S. complaint, VideoShare alleged that Google, YouTube and Vimeo infringed two of its patents regarding the sharing of streaming videos. Google denied infringement.

One of the defences mounted by Google was that the VideoShare invention was not patentable due to “prior art†– an invention that predated the VideoShare patent filing date.  This “prior art” took the form of an earlier video system, known as the POPcast system.  Mr. Mutual, a B.C. resident, was the developer behind POPcast. To verify whether the POPcast software supported Google’s defence, the parties in the U.S. litigation had to come on a fishing trip to B.C. to compel Mr. Mutual to find and disclose his POPcast source code. The technical term for this is “letters rogatory” which are issued to a Canadian court for the purpose of assisting with U.S. litigation.

Mr. Mutual found the source code in his archives, and sought a protective order to protect the “never-public back end Source Code filesâ€, the disclosure of which would “breach my trade secret rights”.

The B.C. court agreed that the source code should be made available for inspection under the terms of the protective order, which included the following controls. If you are seeking a protective order of this kind, this serves as a useful checklist of reasonable safeguards to consider.

Useful Checklist of Safeguards

- The Source Code shall initially only be made available for inspection and not produced except in accordance with the order;

- The Source Code is to be kept in a secure location at a location chosen by the producing party at its sole discretion;

- There are notice provisions regarding the inspection of the Source Code on the secure computer;

- The producing party is to test the computer and its tools before each scheduled inspection;

- The receiving party, or its counsel or expert, may take notes with respect to the Source Code but may not copy it;

- The receiving party may designate a reasonable number of pages to be produced by the producing party;

- Onerous restrictions on the use of any Source Code which is produced;

- The requirement that certain individuals, including experts and representatives of the parties viewing the Source Code, sign a confidentiality agreement in a form annexed to the order.

A Delaware court has since ruled that VideoShare’s two patents are invalid because they claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsSoftware vendors: Do your employees own your software?

By Richard Stobbe

When an employee claims to own his employer’s software, the analysis will turn to whether that employee was an “author” for the purposes of the Copyright Act, and what the employee “contributed” to the software. This, in turn, raises the question of what constitutes “authorship” of software?  What kinds of contributions are important to the determination of authorship, when it comes to software?

Remember that each copyright-protected work has an author, and the author is considered to be the first owner of copyright. Therefore, the determination of authorship is central to the question of ownership. This interesting question was recently reviewed in the Federal Court decision in Andrews v. McHale and 1625531 Alberta Ltd., 2016 FC 624. Here, Mr. Andrews, an ex-employee claimed to own the flagship software products of the Gemstone Companies, his former employer.  Mr. Andrews went so far as to register copyright in these works in the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.  He then sued his former employer, claiming copyright infringement, among other things.

The former employer defended, claiming that the ex-employee was never an author because his contributions fell far short of what is required to qualify for the purposes of “authorship” under copyright law. The ex-employee argued that he provided the “context and content†by which the software received the data fundamental to its functionality.

The evidence showed that the ex-employee’s involvement with the software included such things as collecting and inputting data; coordination of staff training; assisting with software implementation; making presentations to potential customers and to end-users; collecting feedback from software users; and making suggestions based on user feedback.

The evidence also showed that a software programmer engaged by the employer, Dr. Xu, was the true author of the software. He took suggestions from Mr. Andrews and considered whether to modify the code. Mr. Andrews did not actually author any code, and the court found that none of his contributions amounted to “authorship” for the purposes of copyright.  The court stopped short of deciding that authorship of software requires the writing of actual code; however, the court found that a number of things did not  qualify as “authorship”, including

- collecting and inputting data;

- making suggestions based on user feedback;

- problem-solving related to the software functionality;

- providing ideas for the integration of reports from one software program with another program;

- providing guidance on industry-specific content.

To put it another way, these contributions, without more, did not represent an exercise of skill and judgment of the type of necessary to qualify as authorship of software.

The court concluded that: “It is clearly the case in Canadian copyright law that the author of a work entitled to copyright protection is he or she who exercised the skill and judgment which resulted in the expression of the work in material form.” [para. 85]

In the end, the court sided with the employer. The ex-employee’s claims were dismissed.

Field Law acted as counsel to the successful defendant 1625531 Alberta Ltd.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsBREXIT and IP Rights for Canadian Business

By Richard Stobbe

Yesterday UK voters elected to approve a withdrawal from the EU.  What does this mean for Canadian business owners who have intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK?

The first message for Canadian IP rights holders is (in true British style) remain calm and keep a stiff upper lip. All of this is going to take a while to sort out and rights holders will have advance notice of the various means to protect their rights in an orderly fashion. The British are not known for rash actions — ok, other than the Brexit vote.

Rights granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), will be impacted, although the extent of the impact is still to be negotiated and settled. The UK’s membership in WIPO (the World International Property Organisation) is independent of EU membership and so will not be affected by this process. Similarly, the UK’s participation in the European Patent Convention is not dependent on EU membership.

Current speculation is that EU Trade Marks will continue to be recognized as valid in the EU, although such rights will not be recognized in the UK. This may require Canadian rights holders to submit new applications for those marks in the UK, or there may be a negotiated conversion of those EUIPO rights into national UK rights, permitting these registered marks to be recognized both in the EU and the UK.

Copyright law should not be dramatically impacted, since many of the rights of Canadian copyright holders would benefit from international copyright conventions that predate the EU era. However, UK copyright law was undergoing a process to become aligned with EU laws. For example, recent amendments to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were enacted in 2014 to implement EU Directive 2001/29, and the fate of these statutory amendments remains unclear at the moment.

Again, this won’t happen overnight.  Many bureaucrats must debate many regulations before the way forward becomes clear. That’s not much of a rallying cry but it is the reality for an unprecedented event such as this. The good news? If you are a EU IP rights negotiator, you will have steady employment for the next few years.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments

Copyright and the Creative Commons License

By Richard Stobbe

There are dozens of online photo-sharing platforms. When using such photo-sharing venues, photographers should take care not to make the same mistake as Art Drauglis, who posted a photo to his online account through the photo-sharing site Flickr, and then discovered that it had been published on the cover of someone else’s book. Mr. Drauglis made his photo available through a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which permitted reproduction of his photo, even for commercial purposes.

You might be surprised to find out how much online content is licensed through the “Creative Commons†licensing regime. According to recent estimates, adoption of Creative Commons (CC) has expanded from 140 million licensed works in 2006, to over 1 billion today, including hundreds of millions of images and videos.

In the decision in Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group LLC (U.S. District Court D.C., cv-14-1043, Aug. 18, 2015), the federal court acknowledged that, under the terms of the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, the photo was licensed for commercial use, so long as proper attribution was given according to the technical requirements in the license. The court found that Kappa Map Group complied with the attribution requirements by listing the essential information on the back cover. The publisher’s use of the photo did not exceed the scope of the CC license; the copyright claim was dismissed.

There are several flavours of CC license:

- The Attribution License (known as CC BY)

- The Attribution-ShareAlike License (CC BY-SA)

- The Attribution-NoDerivs License (CC BY-ND)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial License (CC BY-NC)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (CC BY-NC-ND)

- Lastly, a so-called Public Domain (CC0) designation permits the owner of a work to make it available with “No Rights Reservedâ€, essentially waiving all copyright claims.

Looks confusing? Even within these categories, there are variations and iterations. For example, there is a version 1.0, all the way up to version 4.0 of each license. The licenses are also translated into multiple languages.

Remember: “available on the internet†is not the same as “free for the takingâ€. Get advice on the use of content which is made available under any Creative Commons license.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

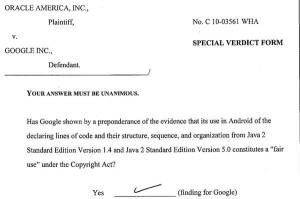

No commentsAndroid vs. Java: Copyright Update

By Richard Stobbe

In a sprawling,  billion-dollar lawsuit that started in 2010, a jury yesterday returned a verdict in favour of Google, delivering a blow to Oracle.  (For those who have lost the thread of this story, see : API Copyright Update: Oracle wins this round).

The essence of Oracle America Inc. v. Google Inc. is a claim by Oracle that Google’s Android operating system copied a number of APIs from Oracle’s Java code, and this copying constituted copyright infringement. Infringement, Oracle argued, that should give rise to damages based on Google’s use of Android. Now think for a minute of the profits that Google might attribute to its use of Android, which has dominated mobile operating system since its introduction in 2007. Oracle claimed damages of almost $10 billion.

In prior decisions, the US Federal Court decided that Google’s copying did infringe Oracle’s copyright. The central issue in this phase was whether Google could sustain a ‘fair use’ defense to that infringement. Yesterday, the jury sided with Google, deciding that Google’s use of the copied code constituted ‘fair use’, effectively quashing Oracle’s damages claim.

Oracle reportedly vowed to appeal.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsDoes Copyright Protect Facts?

By Richard Stobbe

A documentary film is, by its nature, a work of non-fiction. It expresses a set of facts, arranged and portrayed in a particular way. If a fictional novel is written, based on a documentary film, is copyright infringed? Put another way, does copyright protect the “facts” in the documentary?

In the recent Federal Court decision in Maltz v. Witterick, the court considered a claim of copyright and moral rights infringement by the makers of a documentary entitled No. 4, Street of Our Lady about the Hamalajowa family, a real-life family who harboured and saved three Jewish families during the Second World War in Poland. A writer, inspired by the documentary, wrote a fictional young adult novel based on the same real-life experiences of the Hamalajowa family, even going so far as to use many of the same names, the same storyline and facts. The book, entitled My Mother’s Secret, was published by Penguin Canada and went on to become a modest success.

After hearing of the book, the filmmakers sued both the author and Penguin Canada for infringement of their copyright in the documentary film. Although there was no verbatim copying of the dialogue or narrative, the filmmakers claimed that their copyright was infringed in the overall themes, relying on the interesting case of Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, which stands for the proposition that the cumulative features of a work must be considered, and that for the purposes of copyright a “substantial taking” can include similarities such as themes. The filmmakers also argued that a distinction must be drawn between “big facts” and “small facts”. For example, a “big fact” that Polish Jews were captured and deported to concentration camps is not deserving of copyright protection, whereas a “small fact” that a particular Jewish family was taken away from a particular place on a specific day – this kind of fact is deserving of protection, and it was this type of information that was copied by the author from the documentary film without permission.

The court rejected this notion. “The Applicants’ arguments based on differences between “small†and “large†facts, with the former deserving of protection in this case and the latter not so deserving, are without merit. Copyright law recognizes no such difference or distinction. Facts are facts; and no one owns copyright in them no matter what their relative size or significance.” (Emphasis added)

The Court also made an important clarification regarding characters in the story. Citing the Anne of Green Gables decision, the filmakers claimed infringement of the “well-delineated characters” in the film, including the members of the Hamalajowa family. They argued that “the characters in the Book are clearly based on and are virtually identical to the individuals in the Documentary.” This analysis is misguided, according to the Court. “[T]here are no fictional characters in the Documentary; there are only real people or references to and recollections of once real persons, and there cannot be copyright over a real person, whether dead or alive.” (Emphasis added)

The copyright and moral rights claims were dismissed. The important message that is reinforced by this fascinating decision is that the only copyright in the filmmakers’ story lies in their expression of that story and not in its facts.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Infringement Claim Against Canadian Company Stays in U.S.

By Richard Stobbe

Where should a lawsuit be heard? Canada? The US? In other posts we discuss the idea of a “choice of law” and “forum selection” clauses in contracts. In those cases, the parties agree to a particular forum in advance.

What if there is no contractual relationship? There’s just an intellectual property infringement claim. What is the proper forum for that dispute to be heard?

In Halo Creative v. Comptoir Des Indes Inc., David Ouaknine, Case No. 15-1375 (Fed. Cir., Mar. 14, 2016), a recent decision out of the US Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, this issue was reviewed.

Halo Creative, a Hong Kong based furniture maker, launched an IP infringement lawsuit against Comptoir Des Indes, Inc., a Canadian company, and its CEO, claiming infringement of Halo’s U.S. design patents, U.S. copyrights, and one U.S. common law trademark. The lawsuit was filed in the Northern District of Illinois. The Canadian company moved to dismiss the lawsuit based on a “forum non conveniens” argument – essentially an argument that the Federal Court of Canada would be a better place to litigate the claims. The Illinois district court agreed with the Canadians and dismissed the case. Halo appealed.  At the appeal level, the court looked at the adequacy of the Canadian court to litigate this issue.

The Federal Court of Canada was certainly an available forum but there was no evidence that Halo could seek a satisfactory remedy there, since the infringing activity took place in the U.S., and the infringed rights were all based on U.S. registrations or U.S. based trademark rights. IP rights are fundamentally territorial.  The U.S. court even quoted a Canadian textbook: “a Canadian court would not have jurisdiction to entertain in an action brought by an author of a work in respect of acts being committed outside Canada, even if the defendant was within Canada.” (Emphasis added)  Here, there was no evidence that any infringement occurred in Canada.

The motion was dismissed and the lawsuit will proceed in the U.S.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright Injunction Covers Vancouver Aquarium Video

By Richard Stobbe

The Vancouver Aquarium brought an injunction application to stop the online publication of a critical video entitled “Vancouver Aquarium Uncovered”, which used the Aquarium’s copyright-protected materials in a “derogatory manner”, according to the Aquarium.

In the fascinating case of Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre v. Charbonneau, 2016 BCSC 625 (CanLII), the court weighed the Aquarium’s effort to prevent the unauthorized use of their copyright-protected video clips, against the movie producer’s argument that the exposé is on a topic of public interest and shouldn’t be silenced.

This represents the first judicial review of Section 29.21 of the Copyright Act, first introduced in 2012, which covers “non-commercial user-generated content”. In the injunction application the court skimmed over this issue, preferring to leave it to trial. However, the court made passing comments about the availability of a defence which relies on showing that the copyright-protected content was used “solely for non-commercial purposes”. In this case, there was evidence before the court that the movie had recently been screened in Vancouver where attendees had been charged a $10 entry fee. The court also made reference to an Indiegogo fundraising campaign related to the movie production.

Ultimately, the court restricted publication of 15 images and video clips – about 4 minutes worth of content - which the Aquarium claimed to own. The injunction stopped short of attempting to enjoin publication of the whole video, but rather ordered that the defendants remove the 15 contested segments from the video.

If it proceeds to trial, this will be one to watch.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentCopyright Act confers no rights upon animals

.

By Richard Stobbe

Naruto the monkey must abandon his budding photography career and go back to using his opposable thumbs towards some other end. To bring the monkey-selfie case to a close, the US District Court outlined its careful reasoning for rejecting the copyright claims of Naruto, a six-year-old crested macaque. (If you missed the background story, see our earlier post.)

The decision in Naruto v. Slater (US District Court No. Calif. Case 15-cv-04324-WHO) is, if nothing else, a study in restraint. The judge reviews cases involving other non-human claimants, such as the 2004 decision dealing with a claim advanced on behalf of the world’s whales, porpoises, and dolphins, regarding violations of the US Endangered Species Act.

In its final analysis, the court concluded: “Naruto is not an ‘author’ within the meaning of the Copyright Act. Next Friends argue that this result is ‘antithetical’ to the ‘tremendous [public] interest in animal art.’ Perhaps. But that is an argument that should be made to Congress and the President, not to me. The issue for me is whether Next Friends have demonstrated that the Copyright Act confers standing upon Naruto. In light of the plain language of the Copyright Act, past judicial interpretations of the Act’s authorship requirement, and guidance from the Copyright Office, they have not.”

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsWhat does it mean to circumvent a “Technological Protection Measure”?

By Richard Stobbe

Copyright attempts to balance the rights of authors with the rights of users. It’s this tension – copyrights vs. user rights – that makes copyright so fascinating (…to some people).

In 2012, Parliament enacted some changes to Canadian copyright law, which included a number of so-called “user rights” or exceptions to infringement, some of which were conditional on rules dealing with the circumvention of technological protection measures. I’ll give you an example: under section 29.23, recording a TV program for time shifting on your PVR is not an infringement of copyright as long as you did not circumvent a technological protection measure (or “TPM”). So circumvention of a TPM can take you outside the benefit of the exception, with the result that the recording would constitute an infringement.

No court has had a chance to review the rules around TPMs… until the decision in 1395804 Ontario Limited (Blacklock’s Reporter) v Canadian Vintners Association (CVA), 2015 CanLII 65885 (ON SCSM), an Ontario decision which interprets circumvention of a TPM.

A “technological protection measure” is, according to the Copyright Act any “effective technology, device or component” that controls access to a work and whose use is authorized by the copyright owner. It is deliberately broad. The Blacklock’s case dealt with a subscription-based online newsletter published by Blacklock’s. When their CEO was mentioned in a Blacklock’s article, the CVA bypassed the subscriber paywall to access the article. Did the CVA hack into the system and then scrape and republish the Blacklock’s content? No (although such conduct might have justified the $13,000 in copyright infringement damages that were awarded by the judge). The CVA obtained a copy of the article via email, from a colleague who did have a subscription.

According to this case, circumventing a technological protection measure includes obtaining a copy of an article by email, where the article sits behind a paywall. The good news is that no hacking skills are required!

Since this case will not be appealed, it stands as the leading case, although it has been called controversial, bizarre and an extraordinary misreading of copyright law. Since it is the decision of an Ontario small-claims court, it is not binding on other courts in Canada. And since Blacklock’s is pursuing copyright infringement claims against others – there are 10 claims currently filed in the Federal Court – this issue should be canvassed at the Federal Court where further clarification may emerge. Stay tuned.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsArtist Sues Starbucks Claiming Copyright Infringement

New York artist Maya Hayuk was approached by an advertising agency working for Starbucks, to see if she would assist them with a proposed advertising campaign. Ms. Hayuk is known internationally for her paintings using bold colors, and vibrant geometric shapes – rays, lines, stripes and circles.

She declined the offer to work with Starbucks (too busy) and was surprised when she saw the final marketing campaign for the Starbucks Frappuccino product. The marketing materials, including artwork on Frappuccino cups, websites, and on signage at Starbucks’ retail locations and promotional videos, were strikingly similar to Hayuk’s artworks. The artist promptly launched a copyright infringement lawsuit against both Starbucks and its advertising agency, claiming that Starbucks created artwork that was substantially similar to her paintings and further, the Starbucks material appropriated the “total concept and feel†of her paintings, even though there was no “carbon copy” of any particular painting.

Last week, A US District Court handed down its decision in Hayuk v. Starbucks Corp and 71andSunny Partners LLC (PDF) (Case No. 15cv4887-LTS SDNY). It is well settled that copyright does not protect an artist’s style or elements of her ideas. The court denied the claim that any copyright infringement occurred. In analyzing the two images, the court notes that the proper analysis is not to dissect, crop or rotate particular elements or pieces of the two works and lay the isolated parts side-by-side, but rather to look at substantial similarity of the works as a whole. The court concluded that “Although the two sets of works can be said to share the use of overlapping colored rays in a general sense, such elements fall into the unprotectible category of ‘raw materials’ or ideas in the public domain.” [Emphasis added] Thus, there could be no finding of substantial similarity and the claims were dismissed.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsTrademarks and Metatags: an update

.

By Richard Stobbe

What if a competitor cut and paste the metatags from your website and used them on the competitor’s site? Is there a remedy under Canadian law? Are metatags subject to trademark protection? The answer is… it depends.

Red Label Vacations (redtag.ca) sued its rival 411 Travel Buys for use of metatags, including “Red Tag Vacations” in the 411 Travel Buys website. The Federal Court dismissed the trademark and copyright claims of Red Label Vacations (see: No copyright or trademark protection for metatags). Red Label Vacations appealed.

In Red Label Vacations Inc. v. 411 Travel Buys Limited, 2015 FCA 290, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal, and upheld the lower court decision.

The court agreed that 411 Travel Buys had copied the metatags from Red Label’s site, but noted that none of the metatags appeared in the visible portion of the 411 Travel Buys website. Therefore, consumers did not see any of the metatags. In that sense, there was no “use” of the metatags as trademarks for the purposes of determining infringement.

Interestingly, there was one instance where the metatags were visible, and that was in the Google search result, where the words “Book Online with Red Tag Vacations & Pay Less Guaranteed” appeared in connection with the 411 Travel Buys site. The court considered that this would have the effect of sending consumers to Red Label’s site.

The court did leave the door ajar for other metatag trademark infringement cases, noting “in some situations, inserting a registered trade-mark (or a trade-mark that is confusing with a registered trade-mark) in a metatag may constitute advertising of services that would give rise to a claim for infringement…” [Emphasis added]

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments