Bozo’s Flippity-Flop and Shooting Stars: A cautionary tale about rights management

By Richard Stobbe

If you’ve ever taken piano lessons then titles like “Bozo’s Flippity-Flop”, “Shooting Stars” and “Little Elves and Pixies” may be familiar.

These are among the titles that were drawn into a recent copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the Royal Conservatory against a rival music publisher for publication of a series of musical works. In Royal Conservatory of Music v. Macintosh (Novus Via Music Group Inc.) 2016 FC 929, the Royal Conservatory and its publishing arm Frederick Harris Music sought damages for publication of these works by Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music.

The case serves as a cautionary tale about records and rights management, since much of the confusion between the parties, and indeed within the case itself, could be blamed on missing or incomplete records about who ultimately had the rights to the musical works at issue. In particular, a 1999 agreement which would have clarified the scope of rights, was completely missing. The court ultimately determined that there was no evidence that the defendants Conservatory Canada and its music publisher Novus Via Music could benefit from any rights to publish these songs; the missing 1999 agreement was never assigned or extended to the defendants.

In assessing damages for infringement, the court reviewed the factors set forth in the Copyright Act, including:

- Â the good faith or bad faith of the defendant;

- Â the conduct of the parties before and during the proceedings;

- Â the need to deter other infringements of the copyright in question;

- Â in the case of infringements for non-commercial purposes, the need for an award to be proportionate to the infringements, in consideration of the hardship the award may cause to the defendant, whether the infringement was for private purposes or not, and the impact of the infringements on the plaintiff.

In evaluating the deterrence factor, the court noted: “it is unclear what effect a large damages award would have in deterring further copyright infringement, when the infringement at issue here appears to be the product of poor record-keeping and rights management on the part of both parties.  If anything, this case is instructive that the failure to keep crucial contracts muddies the waters around rights, and any resulting infringement claims. The Respondents should not alone bear the brunt of this laxity, because the Applicants played an equal part in the inability to provide to the Court the key document at issue.” [Italics added]

For these reasons, the court set per work damages at the lowest end of the commercial range ($500 per work), for a total award of $10,500 in damages.

Calgary – o7:00 MST

No commentsProtective Order for Source Code

By Richard Stobbe

A developer’s source code is considered the secret recipe of the software world – the digital equivalent of the famed Coca-Cola recipe. In Google Inc. v. Mutual, 2016 BCSC 1169 (CanLII),  a software developer sought a protective order over source code that was sought in the course of U.S. litigation. First, a bit of background.

This was really part of a broader U.S. patent infringement lawsuit (VideoShare LLC v. Google Inc. and YouTube LLC) between a couple of small-time players in the online video business: YouTube, Google, Vimeo, and VideoShare. In its U.S. complaint, VideoShare alleged that Google, YouTube and Vimeo infringed two of its patents regarding the sharing of streaming videos. Google denied infringement.

One of the defences mounted by Google was that the VideoShare invention was not patentable due to “prior art†– an invention that predated the VideoShare patent filing date.  This “prior art” took the form of an earlier video system, known as the POPcast system.  Mr. Mutual, a B.C. resident, was the developer behind POPcast. To verify whether the POPcast software supported Google’s defence, the parties in the U.S. litigation had to come on a fishing trip to B.C. to compel Mr. Mutual to find and disclose his POPcast source code. The technical term for this is “letters rogatory” which are issued to a Canadian court for the purpose of assisting with U.S. litigation.

Mr. Mutual found the source code in his archives, and sought a protective order to protect the “never-public back end Source Code filesâ€, the disclosure of which would “breach my trade secret rights”.

The B.C. court agreed that the source code should be made available for inspection under the terms of the protective order, which included the following controls. If you are seeking a protective order of this kind, this serves as a useful checklist of reasonable safeguards to consider.

Useful Checklist of Safeguards

- The Source Code shall initially only be made available for inspection and not produced except in accordance with the order;

- The Source Code is to be kept in a secure location at a location chosen by the producing party at its sole discretion;

- There are notice provisions regarding the inspection of the Source Code on the secure computer;

- The producing party is to test the computer and its tools before each scheduled inspection;

- The receiving party, or its counsel or expert, may take notes with respect to the Source Code but may not copy it;

- The receiving party may designate a reasonable number of pages to be produced by the producing party;

- Onerous restrictions on the use of any Source Code which is produced;

- The requirement that certain individuals, including experts and representatives of the parties viewing the Source Code, sign a confidentiality agreement in a form annexed to the order.

A Delaware court has since ruled that VideoShare’s two patents are invalid because they claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsSoftware vendors: Do your employees own your software?

By Richard Stobbe

When an employee claims to own his employer’s software, the analysis will turn to whether that employee was an “author” for the purposes of the Copyright Act, and what the employee “contributed” to the software. This, in turn, raises the question of what constitutes “authorship” of software?  What kinds of contributions are important to the determination of authorship, when it comes to software?

Remember that each copyright-protected work has an author, and the author is considered to be the first owner of copyright. Therefore, the determination of authorship is central to the question of ownership. This interesting question was recently reviewed in the Federal Court decision in Andrews v. McHale and 1625531 Alberta Ltd., 2016 FC 624. Here, Mr. Andrews, an ex-employee claimed to own the flagship software products of the Gemstone Companies, his former employer.  Mr. Andrews went so far as to register copyright in these works in the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.  He then sued his former employer, claiming copyright infringement, among other things.

The former employer defended, claiming that the ex-employee was never an author because his contributions fell far short of what is required to qualify for the purposes of “authorship” under copyright law. The ex-employee argued that he provided the “context and content†by which the software received the data fundamental to its functionality.

The evidence showed that the ex-employee’s involvement with the software included such things as collecting and inputting data; coordination of staff training; assisting with software implementation; making presentations to potential customers and to end-users; collecting feedback from software users; and making suggestions based on user feedback.

The evidence also showed that a software programmer engaged by the employer, Dr. Xu, was the true author of the software. He took suggestions from Mr. Andrews and considered whether to modify the code. Mr. Andrews did not actually author any code, and the court found that none of his contributions amounted to “authorship” for the purposes of copyright.  The court stopped short of deciding that authorship of software requires the writing of actual code; however, the court found that a number of things did not  qualify as “authorship”, including

- collecting and inputting data;

- making suggestions based on user feedback;

- problem-solving related to the software functionality;

- providing ideas for the integration of reports from one software program with another program;

- providing guidance on industry-specific content.

To put it another way, these contributions, without more, did not represent an exercise of skill and judgment of the type of necessary to qualify as authorship of software.

The court concluded that: “It is clearly the case in Canadian copyright law that the author of a work entitled to copyright protection is he or she who exercised the skill and judgment which resulted in the expression of the work in material form.” [para. 85]

In the end, the court sided with the employer. The ex-employee’s claims were dismissed.

Field Law acted as counsel to the successful defendant 1625531 Alberta Ltd.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsOh Canada! … in Trademarks

By Richard Stobbe

In honour of Canada Day tomorrow (for our American readers, that’s the equivalent of Independence Day, with the beer, hotdogs and fireworks, but without the summer blockbuster movie to go along with it), here is our venerable national anthem… in trademarks:

OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey), our HOME AND NATIVE LAND (registered for key chains, mugs, coasters and place mats, but expunged for failure to renew in 2012), TRUE PATRIOT LOVE (registered for accepting and administering charitable contributions to support the Canadian Military and their families) in all our sons command (until the lyrics are amended through a private members bill)! WITH GLOWING HEARTS (abandoned) we see thee rise, the TRUE NORTH (registered for footwear namely shoes, boots, slippers and sandals) STRONG AND FREE (registered for T-shirts, sweaters, and hats)! From far and wide, OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey),  WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee! God keep OUR LAND (registered for fresh fruit), GLORIOUS AND FREE (registered for athletic wear, beachwear, casual wear, golf wear, gym wear, outdoor winter clothing and fridge magnets)! OH CANADA (registered for use in association with whiskey) we stand ON GUARD FOR THEE (registered for travel health insurance services, but abandoned in 1996)! WE STAND ON GUARD (registered for water purification systems) for thee!

Happy Canada Day!

Calgary – 12:00 MST

No commentsBREXIT and IP Rights for Canadian Business

By Richard Stobbe

Yesterday UK voters elected to approve a withdrawal from the EU.  What does this mean for Canadian business owners who have intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK?

The first message for Canadian IP rights holders is (in true British style) remain calm and keep a stiff upper lip. All of this is going to take a while to sort out and rights holders will have advance notice of the various means to protect their rights in an orderly fashion. The British are not known for rash actions — ok, other than the Brexit vote.

Rights granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), will be impacted, although the extent of the impact is still to be negotiated and settled. The UK’s membership in WIPO (the World International Property Organisation) is independent of EU membership and so will not be affected by this process. Similarly, the UK’s participation in the European Patent Convention is not dependent on EU membership.

Current speculation is that EU Trade Marks will continue to be recognized as valid in the EU, although such rights will not be recognized in the UK. This may require Canadian rights holders to submit new applications for those marks in the UK, or there may be a negotiated conversion of those EUIPO rights into national UK rights, permitting these registered marks to be recognized both in the EU and the UK.

Copyright law should not be dramatically impacted, since many of the rights of Canadian copyright holders would benefit from international copyright conventions that predate the EU era. However, UK copyright law was undergoing a process to become aligned with EU laws. For example, recent amendments to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 were enacted in 2014 to implement EU Directive 2001/29, and the fate of these statutory amendments remains unclear at the moment.

Again, this won’t happen overnight.  Many bureaucrats must debate many regulations before the way forward becomes clear. That’s not much of a rallying cry but it is the reality for an unprecedented event such as this. The good news? If you are a EU IP rights negotiator, you will have steady employment for the next few years.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Series: Words in a foreign language

By Richard Stobbe

A word that clearly describes a particular product or service cannot function as a trademark for that product or service. The Trademarks Act phrases this idea in a more formal way: section 12(1)(b) says that a trade-mark is registrable if it is not … “whether depicted, written or sounded, either clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive in the English or French language of the character or quality of the wares or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used or of the conditions of or the persons employed in their production or of their place of origin”. (Emphasis added)

The case of  Primalda Industries Corp v Morinda, Inc., 2004 CanLII 71759 (CA TMOB), reviewed an application for the trade-mark TAHITIAN NONI Design, for the following wares: “skin care preparations; namely, cleansers, lotions, gels, moisturizing creams” and similar products. The term TAHITIAN NONI refers to the morinda citrifolia tree, which is commonly known as ‘NONI’ in the Polynesian language.  The application was opposed based on a challenge that the mark offended section 12(1)(b) since it was “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive” of the products, by virtue of the fact that the name is a clear description of ingredients in the skin care products, which are derived from the fruit of the ‘Tahitian NONI’ tree.

This might be like trying to register the word CANADIAN MAPLE in association with skin care products derived from, say, the syrup from the maple tree.

However, after reviewing the Act, the court rejected this ground of opposition. Why?

“It is self-evident from the legislation,” the Court said, “that words that might be descriptive in a language other than French or English are not subject to paragraph 12(1)(b). As the opponent alleges in its statement of opposition that ‘NONI’ is a Polynesian word and there is no evidence that it is an English or French word, I conclude that TAHITIAN NONI Design cannot be unregistrable pursuant to paragraph 12(1)(b).”

In short, a clearly descriptive word can be registrable in Canada as long as it is not descriptive in the English of French language.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCopyright and the Creative Commons License

By Richard Stobbe

There are dozens of online photo-sharing platforms. When using such photo-sharing venues, photographers should take care not to make the same mistake as Art Drauglis, who posted a photo to his online account through the photo-sharing site Flickr, and then discovered that it had been published on the cover of someone else’s book. Mr. Drauglis made his photo available through a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 license, which permitted reproduction of his photo, even for commercial purposes.

You might be surprised to find out how much online content is licensed through the “Creative Commons†licensing regime. According to recent estimates, adoption of Creative Commons (CC) has expanded from 140 million licensed works in 2006, to over 1 billion today, including hundreds of millions of images and videos.

In the decision in Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group LLC (U.S. District Court D.C., cv-14-1043, Aug. 18, 2015), the federal court acknowledged that, under the terms of the CC BY-SA 2.0 license, the photo was licensed for commercial use, so long as proper attribution was given according to the technical requirements in the license. The court found that Kappa Map Group complied with the attribution requirements by listing the essential information on the back cover. The publisher’s use of the photo did not exceed the scope of the CC license; the copyright claim was dismissed.

There are several flavours of CC license:

- The Attribution License (known as CC BY)

- The Attribution-ShareAlike License (CC BY-SA)

- The Attribution-NoDerivs License (CC BY-ND)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial License (CC BY-NC)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (CC BY-NC-ND)

- Lastly, a so-called Public Domain (CC0) designation permits the owner of a work to make it available with “No Rights Reservedâ€, essentially waiving all copyright claims.

Looks confusing? Even within these categories, there are variations and iterations. For example, there is a version 1.0, all the way up to version 4.0 of each license. The licenses are also translated into multiple languages.

Remember: “available on the internet†is not the same as “free for the takingâ€. Get advice on the use of content which is made available under any Creative Commons license.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsDoes Copyright Protect Facts?

By Richard Stobbe

A documentary film is, by its nature, a work of non-fiction. It expresses a set of facts, arranged and portrayed in a particular way. If a fictional novel is written, based on a documentary film, is copyright infringed? Put another way, does copyright protect the “facts” in the documentary?

In the recent Federal Court decision in Maltz v. Witterick, the court considered a claim of copyright and moral rights infringement by the makers of a documentary entitled No. 4, Street of Our Lady about the Hamalajowa family, a real-life family who harboured and saved three Jewish families during the Second World War in Poland. A writer, inspired by the documentary, wrote a fictional young adult novel based on the same real-life experiences of the Hamalajowa family, even going so far as to use many of the same names, the same storyline and facts. The book, entitled My Mother’s Secret, was published by Penguin Canada and went on to become a modest success.

After hearing of the book, the filmmakers sued both the author and Penguin Canada for infringement of their copyright in the documentary film. Although there was no verbatim copying of the dialogue or narrative, the filmmakers claimed that their copyright was infringed in the overall themes, relying on the interesting case of Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, which stands for the proposition that the cumulative features of a work must be considered, and that for the purposes of copyright a “substantial taking” can include similarities such as themes. The filmmakers also argued that a distinction must be drawn between “big facts” and “small facts”. For example, a “big fact” that Polish Jews were captured and deported to concentration camps is not deserving of copyright protection, whereas a “small fact” that a particular Jewish family was taken away from a particular place on a specific day – this kind of fact is deserving of protection, and it was this type of information that was copied by the author from the documentary film without permission.

The court rejected this notion. “The Applicants’ arguments based on differences between “small†and “large†facts, with the former deserving of protection in this case and the latter not so deserving, are without merit. Copyright law recognizes no such difference or distinction. Facts are facts; and no one owns copyright in them no matter what their relative size or significance.” (Emphasis added)

The Court also made an important clarification regarding characters in the story. Citing the Anne of Green Gables decision, the filmakers claimed infringement of the “well-delineated characters” in the film, including the members of the Hamalajowa family. They argued that “the characters in the Book are clearly based on and are virtually identical to the individuals in the Documentary.” This analysis is misguided, according to the Court. “[T]here are no fictional characters in the Documentary; there are only real people or references to and recollections of once real persons, and there cannot be copyright over a real person, whether dead or alive.” (Emphasis added)

The copyright and moral rights claims were dismissed. The important message that is reinforced by this fascinating decision is that the only copyright in the filmmakers’ story lies in their expression of that story and not in its facts.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsIP Infringement Claim Against Canadian Company Stays in U.S.

By Richard Stobbe

Where should a lawsuit be heard? Canada? The US? In other posts we discuss the idea of a “choice of law” and “forum selection” clauses in contracts. In those cases, the parties agree to a particular forum in advance.

What if there is no contractual relationship? There’s just an intellectual property infringement claim. What is the proper forum for that dispute to be heard?

In Halo Creative v. Comptoir Des Indes Inc., David Ouaknine, Case No. 15-1375 (Fed. Cir., Mar. 14, 2016), a recent decision out of the US Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, this issue was reviewed.

Halo Creative, a Hong Kong based furniture maker, launched an IP infringement lawsuit against Comptoir Des Indes, Inc., a Canadian company, and its CEO, claiming infringement of Halo’s U.S. design patents, U.S. copyrights, and one U.S. common law trademark. The lawsuit was filed in the Northern District of Illinois. The Canadian company moved to dismiss the lawsuit based on a “forum non conveniens” argument – essentially an argument that the Federal Court of Canada would be a better place to litigate the claims. The Illinois district court agreed with the Canadians and dismissed the case. Halo appealed.  At the appeal level, the court looked at the adequacy of the Canadian court to litigate this issue.

The Federal Court of Canada was certainly an available forum but there was no evidence that Halo could seek a satisfactory remedy there, since the infringing activity took place in the U.S., and the infringed rights were all based on U.S. registrations or U.S. based trademark rights. IP rights are fundamentally territorial.  The U.S. court even quoted a Canadian textbook: “a Canadian court would not have jurisdiction to entertain in an action brought by an author of a work in respect of acts being committed outside Canada, even if the defendant was within Canada.” (Emphasis added)  Here, there was no evidence that any infringement occurred in Canada.

The motion was dismissed and the lawsuit will proceed in the U.S.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsSocial Media Defamation: the #creeper decision

By Richard Stobbe

A dispute between suburban neighbours escalated and spilled over into social media when one of the neighbours vented on Facebook. The Facebook posts suggested that the plaintiff was a “nutter†and a “creep†who deployed a system of cameras and mirrors to keep the defendant’s backyard and young children under 24-hour surveillance. There was no evidence of any such system. Once the initial comments were posted, they were widely disseminated among the defendant’s 2,000 Facebook “friends†and potentially viewed by any Facebook users due to the “public” settings on the defendant’s Facebook account.

This in turn prompted other comments from the defendant’s Facebook “friends” such as a “pedoâ€, “#creeperâ€, “nutterâ€, “freak†(and more). After about 27 hours, the posts were deleted from the defendant’s account, but by then the same posts had propagated through other Facebook pages ; the court noted dryly that “The phrase ‘gone viral’ would seem to be an apt description.”

The plaintiff, a middle school teacher, was obviously concerned that the posts, as published, could cause him among other things to lose his job or face disciplinary action at his place of employment.

In Pritchard v. Van Nes, 2016 BCSC 686 (CanLII), the court noted that the social media posts constituted attacks on the plaintiff’s character which “were completely false and unjustified. [The plaintiff] has, as a consequence of the defendant’s thoughtless, reckless actions, suffered serious damage to his reputation, and for the reasons set out herein he is entitled to a substantial award of damages.”

The court awarded general damages for defamation of $50,000 and additional punitive damages of $15,000, plus costs.

(See our Defamation Archive)

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTrademark Series: Confusion (Part 2)

By Richard Stobbe

So much confusion, so little time. The Trade-marks Act teaches us that the use of one trade-mark causes confusion with another trade-mark if the use of both trade-marks in the same area would likely lead to the inference that the products associated with those trade-marks emanate from the same person, even if the products are of a different class. Confusion is assessed by looking at all the surrounding circumstances including:

-

the inherent distinctiveness of the trade-marks;

-

the extent to which the marks have become known;

-

the length of time the trade-marks have been in use;

-

the nature of the products or business;

-

the nature of the trade; and

-

the degree of resemblance between the two trade-marks in appearance or sound or in the ideas suggested by them.

In the case of U-Haul International Inc. v. U Box It Inc., 2015 FC 1345 (CanLII), U-Haul International applied to register the trade-marks U-BOX WE-HAUL and U-BOX, for use in association with “moving and storage services, namely, rental moving, storage, delivery and pick up of portable storage units.†A competitor – U Box It – opposed these applications on the basis of confusion with its registered U BOX IT mark for use for use in association with “garbage removal and waste management services.â€Â

Are “moving and storage services” in the same area as  “garbage removal and waste management servicesâ€?Â

U-Haul argued that the two companies offer completely different services, and “that garbage removal and waste management are the ‘exact opposite’ of moving and storage, and in different channels of trade.” However, the court agreed with the opponent’s argument that confusion was based on “the similar manner in which the services are provided, and not on any finding that the services were in fact the same.”

After reviewing all of the factors listed above, the court found a reasonable likelihood of confusion, and refused to register the two marks U-BOX WE-HAUL and U-BOX, based on confusion with the registered mark U BOX IT.

Calgary – 05:00 MST

No comments

Trademark Series: Confusion (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

A interesting Report on Business article by the founder of a Canadian business is useful as a cautionary tale about brand confusion (see: I was outraged when Sobey’s rebranded its chain with the same name as my company). The author of the article tells of her struggles when grocery chain Sobeys launched a brand - FRESHCO – that was identical to the name of her then 15-year old company, also named FRESHCO.  It sounds like a frustrating experience. In particular, the author notes that her company was “federally incorporated across Canada, and not trademarked,” leaving her with no legal options to prevent the entry of Sobey’s FRESHCO brand for grocery store services. For small business owners or start-ups, this might be worth examining with a legal lens:

- First, it’s important to remember that incorporation is completely different from trademark registration. One is creation of a corporate entity, and one is the registration of a brand name. The corporate name sometimes (but does not necessarily) mirror the core brand name of the business. A corporate name is no guarantee of anything in the trademark realm.

- Next, don’t forget that trademark rights are based on use in the marketplace, and a business generates certain trademark rights even without taking the step of registration at the Canadian Intellectual Property Office. In other words, a  business can defend common law trademark rights based on past use even in the absence of a registered trademark. It’s just harder than with a registered mark.

- A registered trademark provides stronger rights across Canada, and that kind of brand protection should always be considered by business owners as part of their investment. Even after an incident like the one described by this author, it’s open to the earlier user of the mark to apply for registration, even after many years of “unregistered” use.

- In this case, the Sobey’s trademark FRESHCO for grocery services is in a different channel of trade than the author’s FRESHCO mark for construction services. Trademark law permits similar or even identical marks to co-exist, so long as consumers aren’t confused. Think of DELTA for hotel services and DELTA for faucets. Identical marks, different channels of trade. There is actually nothing improper about that, as frustrating as it may seem to the earlier user.

The author appears to have used this as a positive opportunity to reinvest in the brand and refocus the company’s marketing message. If this kind of thing happens to your business, ensure that you get legal advice from an experienced trademark lawyer on your options as you make decisions for your company.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsTrademark Series: Deviations!

By Richard Stobbe

The adage “use it or lose it” captures the essence of the ongoing requirement to put a trademark into commercial use. If you abandon your mark, you effectively give up your trademark rights. The corollary is to “use it as registered, or lose it” Not quite as catchy, but just as important.

The Federal Court decision in Padcon Ltd. v. Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP 2015 FC 943 reminds us of this. In this case, a trademark owner obtained a registration in 2006 for the mark THE OUTRIGGER STEAKHOUSE AND BAR in association with “restaurant, bar and pub services”. When challenged, the trademark owner could only show use of the word OUTRIGGER alone, together with the ® symbol, on its menus and on some related promotional materials.Â

Are deviations permitted? When the court considers a mark-as-used against the mark-as-registered, it will consider the following test:

…The practical test to be applied in order to resolve a case of this nature is to compare the trade mark as it is registered with the trade mark as it is used and determine whether the differences between these two marks are so unimportant that an unaware purchaser would be likely to infer that both, in spite of their differences, identify goods having the same origin.

That question must be answered in the negative unless the mark was used in such a way that the mark did not lose its identity and remained recognizable in spite of the differences between the form in which it was registered and the form in which it was used.

The court decided that use of OUTRIGGER alone on menus and promotional materials did not constitute evidence of use of the mark-as-registered: THE OUTRIGGER STEAKHOUSE AND BAR. The registration was expunged.

Lessons for business?

- Review your marks-as-used, and compare against your marks-as-registered.

- Consider developing brand guidelines to ensure that your organization, and others who might be authorized to use your trademarks, are in compliance with the guidelines.

- If you already have brand guidelines, ensure that there are clear lines of responsibility for enforcement.

Calgary – 11:00 MT

No comments

Facebook Follows Google to the SCC

By Richard Stobbe

A class action case against Facebook (see our previous posts for more background) is heading to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The BC Court of Appeal in Douez v. Facebook, Inc., 2015 BCCA 279 (CanLII)  had reviewed the question of whether the Facebook terms (which apply California law) should be enforced in Canada or whether they should give way to local B.C. law. The appeal court reversed the trail judge and decided that the Facebook’s forum selection clause should be enforced.

Facebook now joins Google, whose own internet jurisdiction is also going up to the Supreme Court of Canada this year.

These are two cases to watch.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 comment

Trademark Series: Can a Geographical Name be a Trademark?

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s take an example. Is the word PARIS registrable as a trademark in Canada? A quick search of the registry shows that there are over 250 registered marks which contain the word PARIS for everything from jewelry to software to real estate management services.

A geographical name can be registrable. It depends. The issue is whether the word is “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive” in the English or French languages of the place of origin of the goods or services.

In MC Imports Inc. v. AFOD Ltd., a 2016 case Federal Court of Appeal decision, the court reviewed a challenge to the registered mark LINGAYEN in association with fish sauce and shrimp paste products. The owner of the LINGAYEN mark had sued a competitor for infringement; the competitor sold shrimp paste under a different brand, but the packaging included the phrase “Lingayen Style” to describe its product. This reference to “Lingayen” was, according to the claim, an infringement of the LINGAYEN registered mark.

Lingayen is a municipality in the Philippines known for its distinctive shrimp paste products. Thus, the court found that the use of the phrase “Lingayen Style” was not use of the word for trademark purposes, but was used to describe the place of origin of the goods with which it is associated.  Therefore, there was no infringement.

When considering a geographical trademark, ensure that you seek experienced counsel.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 comments

Trademark Series: Famous Marks in Canada

By Richard Stobbe

Adidas, Veuve Clicquot, Barbie… When is a mark considered “famous†in Canada, and do famous marks enjoy special protection? A handful of Canadian cases have outlined the court’s treatment of well-known brands:

- Sure, Barbie is famous… but not “trump-card†famous. That was the conclusion of the court in Mattel, Inc v 3894207 Canada Inc., when Mattel raised a challenged that the mark BARBIE used in connection with “restaurant services†would lead consumers to make an inference that the restaurant was affiliated with Mattel’s famous BARBIE doll mark.

Canadian Courts will not automatically presume that there will be confusion just because one mark is famous. As the Federal Court in Mattel phrased it, “the fame of the mark could not act as a marketing trump card such that the other factors are thereby obliterated.†Canadian courts will assess all of the surrounding circumstances to determine confusion. In Mattel, they considered the restaurant services to be distinguishable from Mattel’s famous doll.

- The owner of the famous luxury brand VEUVE CLICQUOT encountered similar difficulties in its infringement claim against a purveyor of “mid-priced women’s wear†being sold under the brand CLIQUOT in Quebec.  In Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Boutiques Cliquot Ltée., Veuve Clicquot argued that the association with – sniff – mid-priced apparel was damaging its carefully managed reputation. In an interesting turn of phrase from the decision, the Supreme Court of Canada noted that the champagne maker “has been building its fine reputation with the drinking classes since before the French Revolution.†The role of champagne “drinking classes†as a catalyst for the French Revolution is perhaps a topic for a separate article. In any event, the Court did not find any evidence that the VEUVE CLICQUOT brand image was tarnished, or that the goodwill was otherwise devalued or diluted. The infringement claim was dismissed, leaving the CLIQUOT women’s wear shops free to continue business.

- In a more recent case, shoemaker Adidas challenged a competitor’s registration of a two-stripe design for shoes. Adidas complained that the two-stripe design was confusing with its own three-stripe design. In Adidas AG v. Globe International Nominees Pty Ltd., the Federal Court conceded that “the adidas 3-Stripes Design is well-known, if not famous, in Canada and internationally.†However, in deciding that the two-stripe mark was not confusing with the Adidas 3-stripe design, the Court sounded a cautionary note for owners of famous brands:

“Fame and notoriety associated with a trademark can be a double-edged sword for a trademark owner. On the one hand, an enhanced reputation may provide the owner with extended protection for the trademark beyond goods and/or services covered by a registration for the marks … On the other hand, when a trademark becomes so well known or famous that the public is so familiar with it and readily identifies that trademark as used in the marketplace on goods and/or services, it may be that even as a matter of first impression, any differences between the well-known mark and another party’s trademark, as used on the same or similar goods and/or services, may serve to more easily distinguish the other party’s trademark and reduce any likelihood of confusion.â€

Put another way, a mark can be so well-known to consumers that small differences in a competing mark will enable consumers to distinguish between the two marks.

Get advice on trade-mark protection and infringement from Field Law’s experienced trademark team.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsTrademark Series: What is “use” of a trademark?

By Richard Stobbe

This is a story of what “use” really means. In the internet context, a trademark can be displayed on a website by a Canadian company, and that website can be accessed anywhere in the world. Similarly, a foreign company can display its mark on a website which can be accessed by Canadian consumers. Is the foreign company’s mark being “used” in Canada for trademark purposes, merely by being displayed online to Canadian consumers?

If you follow this kind of thing… and who doesn’t?… you would say that this issue was settled in the 2012 case HomeAway.com, Inc. v Hrdlicka, [2012] FCJ No 1665 where Justice Hughes said clearly: “a trade-mark which appears on a computer screen website in Canada, regardless where the information may have originated from or be stored, constitutes for Trade-Marks Act purposes, use and advertising in Canada.”

Not so fast.

In Supershuttle International, Inc. v. Fetherstonhaugh & Co., 2015 FC 1259 (CanLII), the court reviewed  a challenge to the SUPERSHUTTLE trademark, which was registered in connection with “airport passenger ground transportation services”. The SUPERSHUTTLE mark was displayed to Canadian consumers who could reserve airport shuttle transportation in the United States. The mark was registered in Canada and displayed in Canada, but no shuttle services were actually performed in Canada. The court concluded that: “While the observation of a trademark by individuals on computers in Canada may demonstrate use of a mark, the registered services must still be offered in Canada.” (Emphasis added)

Non-Canadian trademark owners should take note: merely displaying a mark in Canada via the internet may not be enough for “use” of that mark in Canada. The services or products which are listed in the registration must be available in Canada. Make sure you get experienced advice regarding registration of marks in Canada.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsClass Action Against Google’s Crowd Sourcing

By Richard Stobbe

By Richard Stobbe

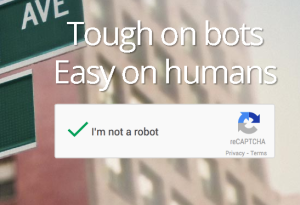

Most of us have had to pass through a CAPTCHA screen in order to log in or use a web-based service. This often involves deciphering and typing in one or two garbled words.  One of the more popular screens is operated by Google and known as reCAPTCHA.

When Google recruits your human brain to decode text in the reCAPTCHA screen, it is doing two things: it is providing a service that protects websites from bots, automated spam and abuse, “while letting real people pass through with ease.”  Second, it is deciphering text that stumps OCR technology, all the while teaching its own robots, through machine learning, to improve their predictive analysis of human text. (We can have a philosophical discussion about how being “tough on bots” is actually teaching the bots to read like humans… but that’s a topic for another day).

Put another way, “Google is ‘crowd sourcing’ the transcription of words that a computer cannot decipher.” In a fascinating decision (GABRIELA ROJAS-LOZANO, v. GOOGLE, INC.),  a California court has dismissed a class action claim that users deserved some compensation for the service they were providing to Google.  To paraphrase, the lawsuit alleged that Google failed to disclose that the second reCAPTCHA word was used for transcription services (from which Google profits) rather than for website security purposes.

However, according to the judge, profit by Google does not translate into a loss for the user who performs this micro-task, which takes each user only a few seconds.  Plaintiff could not cite any case that supports the theory that a non-employee transcribing a single word is owed compensation.  Since this is such a small amount of time, and there was no loss, damages or reliance on the part of the user, and no actionable misrepresentation or unjust enrichment on the part of Google, the court concluded that the class action should be dismissed.

Hat tip to Professor Eric Goldman, who calls this “one of the most interesting Internet law rulings so far in 2016.”

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsCASL Enforcement (Part 2)

.

By Richard Stobbe

As reviewed in Part 1, since July 1, 2014, Canada’s Anti-Spam Law (or CASL) has been in effect, and the software-related provisions have been in force since January 15, 2015.

In January, 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) executed a search warrant at business locations in Ontario in the course of an ongoing investigation relating to the installation of malicious software (malware) (See: CRTC executes warrant in malicious malware investigation). The allegations also involve alteration of transmission data (such as an email’s address, date, time, origin) contrary to CASL. This represents one of the first enforcement actions under the computer-program provisions of CASL.

The first publicized case came in December, 2015, when the CRTC announced that it took down a “command-and-control server” located in Toronto as part of a coordinated international effort, working together with Federal Bureau of Investigation, Europol, Interpol, and the RCMP. This is perhaps the closest the CRTC gets to international criminal drama. (See: CRTC serves its first-ever warrant under CASL in botnet takedown).

Given the proliferation of malware, two actions in the span of a year cannot be described as aggressive enforcement, but it is very likely that this represents the visible tip of the iceberg of ongoing investigations.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentCASL Enforcement (Part 1)

.

By Richard Stobbe

Since July 1, 2014, Canada’s Anti-Spam Law (or CASL) has been in effect, and the software-related rules have been in force since January 15, 2015.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see a few patterns emerge from the efforts by the enforcement trifecta: the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the CRTC and the Competition Bureau. (For background, see our earlier posts) What follows is a round-up of some of the most interesting and instructive enforcement actions:

This certainly points to the more technical risks of poorly implemented unsubscribe features, rather than underlying gaps in consent. Perhaps this is because heavy enforcement action related directly to consent is still to come. Implied consent can be relied upon during a three-year transitional period. After that window closes, expect enforcement to focus on failures of consent.

To put this all in perspective, consider enforcement of other laws within the CRTC mandate: in 2014 the CRTC did not issue any notices of violation of CASL, but issued 10 notices of violation related to the Unsolicited Telecommunications Rules and the National Do Not Call List (DNCL); in 2015 the CRTC issued 1 notice of violation of CASL and about 20 related to the Do Not Call List.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 comment